Address Point: All the valid addresses in Delaware County. It is updated frequently and published every month.

Annexation: All the annexations and their boundaries in the county. This is updated and published every month.

Condo: All of the condos in the county. This is recorded and updated by the county recorder’s office.

Dedicated ROW: This is all the designated road right-of-way lines. It is updated daily and published every month.

Farm Lot: This is the farmlots in both the US Military and Virginia Military Survey Districts within Delaware County. It is updated every month.

GPS: Identifies all the GPS monuments established in 1991 and 1997. This is updated on an as-needed basis, the last time was 2021.

Hydrology: This is all major waterways in Delaware County. Updated as needed and published monthly.

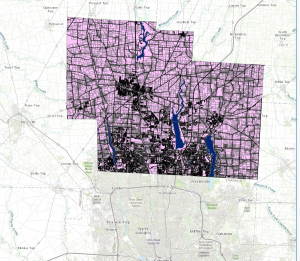

MSAG: The boundaries of all the 28 political jurisdictions that are within Delaware County. It is updated as needed and published monthly.

Map Sheet: Consists of all map sheets within Delaware County. Last updated 2/28/2025.

Municipality: Consists of all the municipalities within the county. Last updated 2/28/2025.

Original Townships: This is the boundaries of the original townships within Delaware County before they were changed based on tax districts. Last updated 4/17/2020

PLSS: Public land survey system polygons in both the US military and Virginia Military Survey Districts within Delaware County. Updated Monthly.

Parcel: Consists of polygons that represent all the cadastral parcel lines in the county. Updated Monthly.

Precinct: Consists of the voting precincts within the county. Last updated 5/3/2023.

Recorded Document: Plots recorded documents from the Delaware County Recorder’s Plat Books, Cabinet/Slides, and Instruments Records, including vacations, surveys, and annexations. Updates published monthly.

School District: Consists of all the school district lines within the county. Updated monthly.

Street Centerline: The State of Ohio Location Based Response System Street Centerlines of private and public roadways. Updated daily and published monthly.

Subdivision: Consists of all subdivisions and condos in the county. Published monthly by the county recorder’s office.

Survey: Survey points is a shapefile of a point coverage representing surveys of land within the county. Last updated 2/28/25.