My name is Colin Counahan. I am a Junior on the Lacrosse team. I am from the greater Columbus area. I am majoring in Education Studies and am minoring in Communications, Religion, and History. In my free time, I enjoy traveling and playing golf.

Geography 291: Geospatial Analysis with Desktop GIS

Module 1: 1/14/2026 to 3/3/2026, OWU Environment & Sustainability

My name is Colin Counahan. I am a Junior on the Lacrosse team. I am from the greater Columbus area. I am majoring in Education Studies and am minoring in Communications, Religion, and History. In my free time, I enjoy traveling and playing golf.

Hi! My name is Kelsea Cooper and I am a junior double majoring in Public Health and Genetics! I am from Kent, Ohio. I have a cat named Marlin (he is very mischievous). In my free time I like to read, craft, and watch TV!

(Also including a photo of Marlin)

(Also including a photo of Marlin)

The whole reason I am taking this course is because of GIS’s application within public health so I was very excited that it was mentioned right out of the gate. It was really cool to learn about how GIS started by just layering paper on top of each other to initiate a whole field of study. In this section, I also learned the difference between spatial analysis and mapping. Spatial analysis generates information from maps and data where mapping simply represents the geographic data. Moving on to the section about “The Messy Business of Digging For Roots: GIS’s Intellectual Antecedents,” there was a specific quote that stood out to me which was “GIS is a relative newcomer to geography.” Although this is a very simple quote, it provoked quite a bit of thought because it prompted me to think about the grand scheme of things in terms of how long maps have been around and then when putting it on a timeline, GIS is on the very end of the timeline. Although it has been around for a short time on this scale, it has made tremendous impacts on so many different fields, including my own. As I mentioned above, I am a Public Health major and I wanted to take this course because there is so much application of GIS within the field. Schuurman mentions how important GIS is when monitoring outbreaks or when identifying areas of health disparities (just to name a few applications). Given this timeline and the timeline of when we really started to fully understand communicable diseases, I think that we are so lucky as a population that they were close to each other on this timeline. This also ties into another point Schuurman made about how virtually everything you have or eat/rely on these days now relies on GIS in one form or another. Overall, this reading made me very excited to explore all of the different applications within GIS and all of the good it can be used for!

Here are my searches:

#1: My search was “smoking prevalence and access to health outcomes” but I was able to find this article called “Mapping a COVID-19 vulnerability: Areas of South and Midwest have fewer hospital beds and higher smoking rates”

This is a map that depicts each US county by smoking rate and hospital capacity. This is very important because not only is smoking more prevalent in areas that have lower socioeconomic status, but in addition, those areas also have less access to health care facilities. In this case, it also in concern with Covid-19, which smoking increases a person’s risk of severely being impacted by Covid-19.

Mapping a COVID-19 vulnerability. (2019). Truth Initiative. https://truthinitiative.org/research-resources/smoking-region/mapping-covid-19-vulnerability-areas-south-and-midwest-have-fewer

#2: My search was “US smokeless tobacco prevalence” I wasn’t really looking to compare this to any type of health outcome in this search, I was just curious what it would be across the US. However, when I was searching through some images, I found this one that compares global smokeless tobacco (SLT) prevalence to policies that country has in place, “The global impact of tobacco control policies on smokeless tobacco use: a systematic review”

00205-X/asset/99d69831-e43f-4808-a21e-2215c27e6abe/main.assets/gr3_lrg.jpg)

The shading of each country indicates the prevalence of SLT usage, then there are icons also on each country to indicate what types of policies are in place for that country. I like the premise of the icons indicating policies but I will say it is a bit hard to read, especially for countries that are geographically smaller.

Chugh, A., Arora, M., Jain, N., Aishwarya Vidyasagaran, Readshaw, A., Sheikh, A., Eckhardt, J., Siddiqi, K., Chopra, M., Masuma Pervin Mishu, Kanaan, M., Rahman, M. A., Mehrotra, R., Rumana Huque, Forberger, S., Suranji Dahanayake, Khan, Z., Boeckmann, M., & Omara Dogar. (2023). The global impact of tobacco control policies on smokeless tobacco use: a systematic review. The Lancet Global Health, 11(6), e953–e968. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2214-109x(23)00205-x

Hi! My name is Camryn Henderson, and I am a freshman. I am an Environmental Studies and Theater double major with a minor in Politics and Government. I am from Wadsworth Ohio, which is near Akron.

2. Schuurman reading

This chapter was an introduction to GIS, but instead of being a guide on how to use it, it instead it dove into why it is used, the best applications for it, and explained its importance to not only geography but all areas of study. Before reading this chapter, I was unaware of the problems that can occur from using GIS, and I didn’t know that there could be significant faults in using it. I also found the history of GIS interesting, as I feel it gave better insight into what the program is used for and showed a clear difference between GIS now and originally. I did not not know much about GIS in general before reading this and I found that it gave a good overview of the general knowledge needed to do well in this course. I did not know that there was a difference between “mapping” and “spatial analysis” but learning about the differences between the two was super interesting. Spatial analysis is a term I have heard come up a lot in Environmental Science classes so learning a little bit more about what it is and vast amount you can learn from it was helpful. I chose to take this class not only to fulfill a requirement but also because as I have been doing research for internships, and possible future jobs I have noticed how important it is to be familiar with GIS, and spatial analysis; however I knew very little about what kinds of things I could use GIS for, and this book gave me more insight. Other than for urban planning and other environmental focused careers, I had not heard of GIS being used; however it can be used for sales, transportation, and health professions. This chapter provided me with baseline knowledge that I will be able to use throughout the semester.

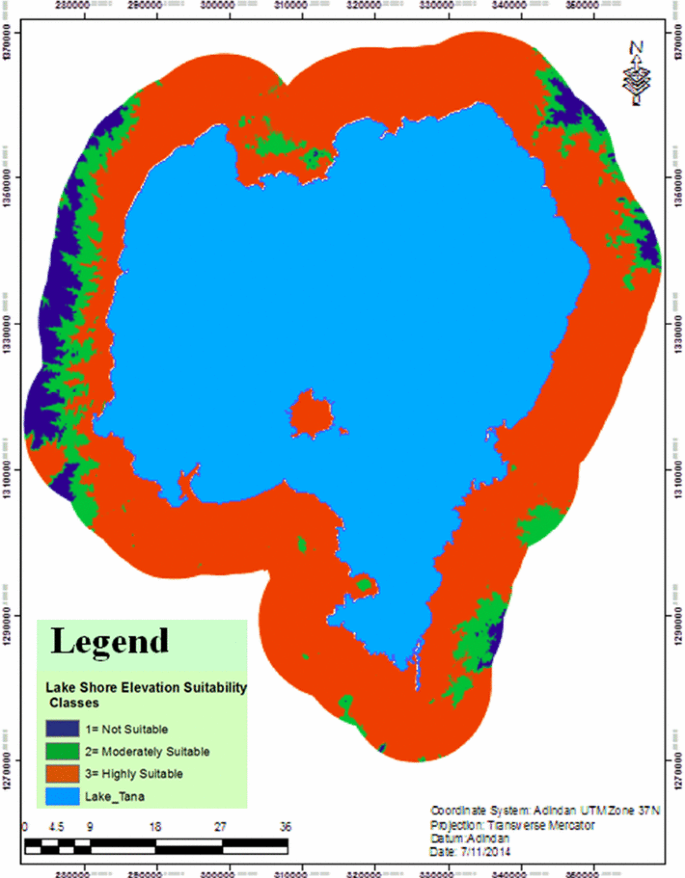

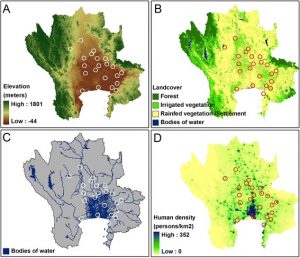

3. Buruso, F.H. Habitat suitability analysis for hippopotamus (H. amphibious) using GIS and remote sensing in Lake Tana and its environs, Ethiopia. Environ Syst Res 6, 6 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40068-017-0083-8

This is a GIS image of the elevation sutiability for hippos in Ethiopia near Lake Tana. In the article where I found this analysis I found many others, all covering different criteria and their respective suitability. They were able to reclassify the data and determine suitability by elevation in this case.

Sarma, P. K., Mipun, B. S., Talukdar, B. K., Kumar, R., & Basumatary, A. K. (2011). Evaluation of Habitat Suitability for Rhino (Rhinoceros unicornis) in Orang National Park Using Geo-Spatial Tools. International Scholarly Research Notices, 2011(1), 498258. https://doi.org/10.5402/2011/498258

This image is from a similar study to the first one; however, this time it was focusing on the conservation of rhinos. Due to rhinos being endangered it is very important for their habitats to be as preserved and suitable as possible. This study focused on suitability in different parts of a National Park in India.

Hello! My name is Ashley Bahrey and I am a junior Zoology, Environmental Science, and Geography major. I am from Bristolville, Ohio and I like to make jewelry and crochet in my spare time. I also have three cats that I love and adore!!!

I am one of the people that Nadine Schuurman is talking about in chapter 1 of GIS: A Short Introduction that previously did not know many of the core ways in which GIS is integrated in my daily life. The discussion around how GIS does not have a rigid identity because it is used to ask both where spatial entities are and how spatial entities may be encoded made me begin to consider just how interdisciplinary the use of GIS must be. I found Schuurman’s way of differentiating between spatial analysis and mapping by pointing out that mapping does not create more information than was originally provided to be very helpful in understanding these concepts. While Canada was credited for developing one of the earliest computer cartography systems, I thought it was interesting that GIS roots emerged somewhat simultaneously around the world in the 1960s. I really appreciate the lengths that Schuurman goes to make the content of this chapter straightforward and accessible. Her comparison of GIS to a calculator nicely set up the conversation she creates around GIS as a tool that can be used to visualize spatial data and “utilize fuzzy data”. Thinking of the visual aspect of GIS as a means of increasing the accessibility of spatial analysis is intuitive to me and definitely underscores the importance of GIS as a method of communicating big ideas in ways that can be digested by people with varying backgrounds. I also found the discussion surrounding the differences between GISystems and GIScience to be very informative, providing context for a new focus on researching the technical and theoretical problems associated with GIS. Additionally, the point that Schuurman raises about how map readers may interpret symbols and map representation differently seems paramount to visualizing spatial data in a way that can be accurately and efficiently utilized. Detailing some of the many ways that we rely on GIS in our everyday lives sets the stage for Schuurman’s overarching point that the intellectual and disciplinary ties of GIS must be studied in tandem with the technology itself to understand how modern society is organized and influenced by the digital realm.

Search 1: “GIS Application Eastern Bluebird Population Monitoring“

This is a species distribution map for eastern bluebirds (Sialia sialis). While eastern bluebirds are categorized as of least concern (LC) on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, it is important to understand the range and habitat use of this species because these birds experienced serious population declines beginning in the early 20th century due to competition with invasive species and pesticide use. As low-aggression secondary cavity nesters, bluebirds were left with fewer places to nest. The installation of cavity nesting boxes designed to keep the larger birds like the invasive European Starling and bluebirds trails caused populations to rebound in the 1960s. Now, the population trend for eastern bluebirds is increasing.

BirdLife International (2025) Species factsheet: Eastern Bluebird Sialia sialis. Downloaded from https://datazone.birdlife.org/species/factsheet/eastern-bluebird-sialia-sialis on 16/01/2025.

Search 2: “GIS Socioeconomic Status and Environmental Contaminants“

This is a map of three ranges of critical health code violations (CHV) in 10,859 retail food service facilities overlaid on a map of poverty levels by census tracts in the city of Philadelphia, PA. The large number and close proximity of food service facilities make visual interpretations of mapping difficult, but this study found that food service facilities in higher poverty areas had a greater number of facilities with at least one CHV and underwent more frequent inspections compared to those in lower poverty areas. Additionally, the results of this study showed that facilities in census tracts with high concentrations of Hispanic populations had more CHVs than those in other demographic areas (Darcey & Quinlan 2011).

Darcey, V. L., Quinlan, J. J. (2011). Use of Geographic Information Systems Technology to Track Critical Health Code Violations in Retail Facilities Available to Populations of Different Socioeconomic Status and Demographic. Journal of Food Protection 74(9): 1524-1530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygcen.2008.05.017

Hi! My name is Iris Urton. I am currently a freshman and am an Environmental science major with an interest in minoring in botany or zoology.

Before I decided to take this class I had no idea what GIS even was or what it stood for and even reading the course description I had no idea it has so many uses in our modern world besides environmental purposes. I find it interesting how philosophy plays into this by the way that its use and meaning changes based on the intentions of the user. Spatial analysis is very different from mapping apparently, and in the early days if GIS on was just referred to as the computerized version of the other because the immense application of this tool was not yet fully realized. Many rejected the idea of GIS at first because they didn’t see a benefit in using it if they could do the exact same thing on paper but it could do a lot more than that, it just wasn’t given a chance at first. The roots of GIS are hard to pinpoint because its development came at a time when all sorts of information were starting to be digitized. Not only did geographers start to use it but so did landscapers, surveyors and architects. I didn’t realize how long GIS has really been a thing and I can understand why cartographers were slow to change but I think it’s really incredible how GIS allows you to overlay information to get a clearer picture on the question you’re trying to answer. I wonder if GIS would be what it is today if people hadn’t started to ask questions about the accuracy of the system and how it can be made better. The thought that there could be a gender bias in how the system is used is very interesting to me and that the consequences of it can be bigger than we think. As an outdoorsy person I didn’t think that GIS would be something that really would interest me because I’ve always wanted to do something very hands-on and in the field like conservation but in the modern age I realized after reading this that it is becoming a very important tool and can be combined with many specializations including conservation.

For my first application of GIS to look into I chose the conservation of endangered species. What I found is that with climate change still an ever prevalent issue in today’s world, our vast biodiversity of life is being threatened. The number of endangered species is rising but GIS has been an incredibly helpful tool in combating this issue. It allows conservationists to monitor and visualize population distribution, both historical and present, and track the efforts of the conservationists. They are also more easily able to gain better insight on where efforts are most needed.

Source: https://geo-jobe.com/mapthis/wildlife-conservation-powered-by-gis/

Another application of GIS I wanted to look into is about fox bats because they are one of my favorite animals and I find them really interesting. Something I learned from researching this topic is that fox bats are carriers of the Nipah virus and the transmission of the virus is due to habitat loss causing them to have to migrate to more populated areas, increasing the risk of human transmission. Pig farms are also a main source of potential contamination and happen to be a big part of Thailand agriculture. To prevent a possible spread of disease GIS is being used to map potential contact between bats, pigs and humans and to track bat colonies’ whereabouts.

Source:https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4389713/

My name is Zachary Kyan Crane, going by Kyan, and I am currently an Environmental Studies major. I am from a small town on the West Virginia side of the Ohio River named New Martinsville (about 45 minutes to an hour South of Wheeling). I’m a big fan of skateboarding/snowboarding (bad at both though), biking, and just about anything you can waste your time doing on a tv/pc.

If I was asked to create a new slogan for GIS it would go along the lines of “Seeing is Believing.” In my opinion from what I gained from the chapter, GIS is a tool used to streamline and organize geographical data through visual imagery. It is clear that the way that any data is visually represented for the human brain to comprehend is imperative for any kind of planning or organization. I can totally see myself struggling to understand data points on a representing graph more than a comprehensive map. Within this humanization is the incredibly important need to organize a large amount of different points of data into one maneuverable format. I’m actually pretty excited to see all the different layers that a map can have and all the different variables that can be brought into one space. However, there is a need to recognize that this is not the end all of mapping and that GIS is more of an organization tool than a computing tool. I understand that for anyone using GIS it is still important to be able to actually understand the data being visualized so that I can be added upon, changed, or used for a project of some sort. One thing about all this that I felt seemed somewhat given were all of the different uses of GIS. It makes a lot of sense to me that many different projects and jobs use this technology to plan and understand the land that they are working on. It is incredibly important to understand the setting of whatever is about to happen.

One of the first things that came to mind for something that uses or is similar to GIS is a video game called Cities: Skylines. Its just a game where you build a city, but there is a complex info panel that shows you everything from mineral deposits to the happiness of your citizens. The 20+ overlays that can be accessed are all needed to sufficiently run your city.

https://www.esri.com/about/newsroom/arcnews/arcgis-urban-transforms-city-planning/

This is what this kind of thing looks like for real life applications in urban planning. Another good application that can relate back to urban planning is how to engineer the structures that have been assigned somewhere to be built.

https://www.esri.com/en-us/industries/aec/business-areas/design-engineering

Hello! My name is Owen Smith, I am currently a senior at Ohio Wesleyan University, majoring in zoology. I am in the application process for jobs after school, I would like to be a game warden. I was interested in taking GIS courses because I will use them in the field I plan on working in. I wanted to familiarize myself with GIS and master how it works.

As I went through the reading, it was very thought-provoking, and I had many comments and questions. My natural inclination toward GIS and mapping as a whole was strictly limited to the geospatial mapping of physical formations. Thankfully, I have taken classes with Ashley Toenjes as she has poked many holes in my definition of what GIS is. while reading, I realized how succinct her classes and definitions were with what Schuurman was saying on page 3. When they spoke about the identity crisis that GIS faces. Another thing I found interesting was how new GIS is, in the grand scheme of mapping. Logically, it makes sense though, the computing power needed to make these extremely complex maps has only recently become accessible for most everyone.

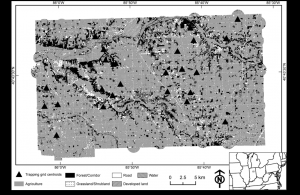

One application of GIS that I found applied to me was the use of data analysis in the workplace. As an outdoorsy person being able to use GIS opens up a plethora of job opportunities. For example, the state of Montana is actively hiring employees to use GIS and analyze natural resource data. I chose to look into invasive plant species in Siberia. Having taken several plant/climate-based classes. So, looking into the mapping of invasive plant species and thier migration due to climate change was something that really stuck out to me. The attached map is just one of the several images used to show the locations the invasive species were found.

Hi! My name is Grace Kopelcheck and I am currently a senior majoring in zoology! I currently work at the Columbus Zoo and Aquarium as a seasonal zookeeper in the Animal Encounters region (right next to the sea lions!). I have also volunteered at the Ohio Wildlife Center for a little over a year, as well as have interned in the Asia Quest region for a semester! Currently this semester I am interning at Cosi with their animal care team!

When reflecting on the reading I had many comments and thoughts throughout the reading. Firstly when reading the first page I was shocked to learn that GIS can rationalize organ donations. I always thought that GIS was used for more land mapping, but I did not realize the full extent of the content GIS can create/explore. I also never realized the social implications of GIS and what it can do to expand on things other than land. It’s also interesting to read that GIS is considered to have an identity crisis. I think this is funny as well as interesting as I even thought of a different identity for GIS than what it has been used for. I also find it interesting how much we have utilized GIS even though it was stated in this paper that it was a newer technology. This use of newer technology becoming an upcoming feature for many companies and usage reminds me of AI and how this a new very utilized technology as well. It was also interesting to read how one challenge GIS faces is being able to draw strict boundaries represented with lines drawn from GIS. Overall this reading was interesting and gave me a better understanding of the capabilities that GIS has and can do.

For looking into sources of GIS applicable/interesting to me, I used the key subject of Virginia Opossum (as they are my favorite animal) to find GIS application. I found two interesting articles talking about the population distribution of Virginia Opossum and how they move towards human populations due to food (Beatty et al. 2016). Another article tracked the same information however with road kill found and the findings of human influence land types and the amount of roadkill found had negative correlations (Kanda et al. 2006). GIS proves useful in tracking local populations of animals! Below are some GIS maps from both these articles that show the land that Virginia Opossum were found to inhabit (both dead and alive).

Beatty, W. S., Beasley, J. C., Olson, Z. H., & Rhodes Jr, O. E. (2016). Influence of habitat attributes on density of Virginia opossums (Didelphis virginiana) in agricultural ecosystems. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 94(6), 411-419.

Kanda, L. L., Fuller, T. K., & Sievert, P. R. (2006). Landscape associations of road-killed Virginia opossums (Didelphis virginiana) in central Massachusetts. The American Midland Naturalist, 156(1), 128-134.

My name is Spencer Yates, and I am a microbiology and zoology major. I’m currently applying to graduate schools with areas in virology. The reading was very interesting to me. I had no idea that GIS software was so important to modern research and engineering. I thought it was just for geographic research, but it’s much more broad than that. The creation of the GIS software is also fascinating, as it involved so many people all across the world over a large period of time. It is kind of hard for me to understand so far, as I’ve never really done mapping before. However, I am determined to master GIS by the end of this course. I think that this skill will be really useful for me in the future.

When I looked for applications of GIS that are interesting to me, I chose two categories: professional interest and personal interest. For professional interest, I looked up if GIS is useful for tracking the progression of diseases. There are a lot of examples of this, but I found a recent malaria study using GIS mapping to explore the prevalence of the disease in Nigeria to be the most fascinating. The paper used GIS mapping to show the changes in prevalence in areas of Nigeria over a 20-year period, which is incredibly useful to know. Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00436-024-08276-0#Tab2

As for a more personal interest, I chose butterfly migration and conservation. In this category, monarch butterfly migration and habitat appeared to be a highly studied area. I found an interesting example of mapping the amount of suitable overwintering habitat for monarch butterflies in Mexico. While this map is only for one point in time, making similar maps in the coming years can allow for the tracking of habitat gain and loss, which can let researchers know if conservation efforts are effective or not. Source: https://creeksidescience.com/what-we-do/gis-analysis/

The blog is not letting me upload either of the maps I found, but they are in the links if you want to see them.

Hello! I’m Ariauna Hickman. I’m from Pittsburgh Pennsylvania. I’m a sophomore, majoring in Pre-Professional Zoology on the Pre-Veterinary track. I am also double minoring in business and chemistry. A quick fun fact is that I have a Great Dane who is a goofball.

After reading Schuurman ch. 1, it is clear to see how important GIS is in many different career choices. I like how it can be used for many different things. The part where it mentions how municipalities use it for things like affects on highways, however, confuses me a bit. How are they able to tell how it affects those areas? Now that I read the next page, my question was answered. It is to see how it would work with landscapes and housing. It is crazy to think about how more than 50% of our brains neurons are used for visual intelligence. No wonder GIS is so important. It is like a visual way of seeing geographical locations. The visuality is used as a means to be able to make it more accessible to see the patial awareness of areas.

After looking at a few different ways that GIS is used. I found how it can be used for video games. For example, Watch Dogs 2 usesGIS in the way that it is open world. They made it highly detailed and realistic with the urban planning, architecture, and digital infrastructure. GIS is also used in Pokemon GO. People go around using a geographical map that matches their location to go and catch different pokemon. It is a blend between the physical and digital world.

Geographic Information Systems, Intersections, Iowa Computer Science Education Week 2023, Technology, Video Games, Video Games and GIS, Wael Alhaj