Hello everyone! My name is Bret Becker, and I am a junior at Ohio Wesleyan. I am a physics and environmental science double major with a minor in social justice. I love to play sports and be outside. Also, you might see me working at the Pulp right off campus if you ever stop in. I’ll just mention that I took the quiz right here because I’m not sure where else to.

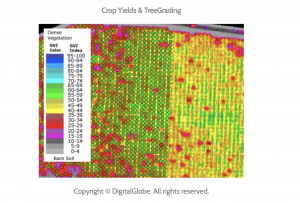

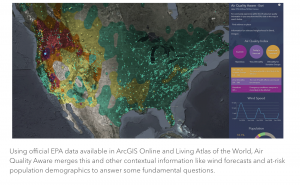

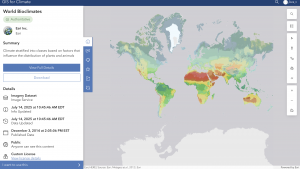

While reading chapter one from Schuurman, I learned a lot more about the history of GIS and how it is continuing to evolve. The wide variety of uses for GIS were fascinating to read about, and it was interesting to learn about the disputes among geographers about GIS. A large part of the text discussed the distinction between understanding the potential uses for GIS and understanding how GISystems work. GIS started to develop in the 1960s with Ian McHarg and his goal to develop the optimal route for a highway. McHarg’s work paved the way for the development of spatial analysis, and spatial analysis being done on the computer was undervalued until Harold McCarty and William Garrison started to pioneer it, later followed by the formation of computerized cartography systems in Canada by Roger Tomlinson and Lee Pratt. As GIS has continued to evolve, it has been understood to form into two different categories: GISystems and GIScience. GISystems focuses on the actual systems developed whereas GIScience focuses on how these systems work. GIS can be used for a wide variety of things, like food production and even e-commerce as mentioned in the book. But GIScience is an important part of making sure the systems work properly and without bias. It is important to not what data is collected as well as how it is collected. Not only that, but it is important to note who produces and controls these systems, as well as the potential harms that could become prevalent when it comes to individual data privacy. GIS is an important, new, and emerging tool that can be useful to help us better get visual representations of data to then analyze, but it is also important to make sure we are ethically using and setting these systems up. Schuurman does a good job mixing the hopefulness and power of GIS with the precautionary tones we must have to proceed.

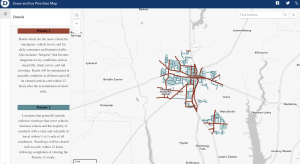

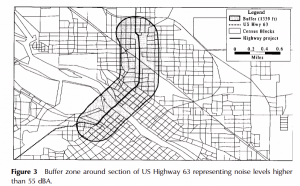

An interesting application of GIS I found in the environmental justice realm was using it to investigate areas of higher noise level and the demographics of people that live there. One study using this method found that a buffer area with high amounts of noise near US Highway 63 had disproportionate amounts of nonwhite and low-income people living there in proportion to the rest of the city.

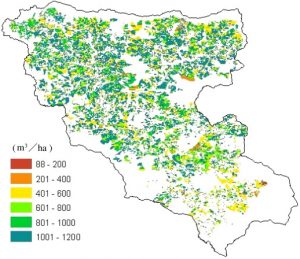

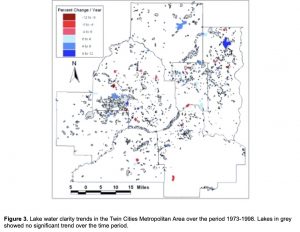

GIS can also be applied to resource management strategies. This could potentially be used to track water flow and to help fine tune water management in areas.

Sources

Crenganiş, M., L. & Telişcă, M. GIS application in water resources management and environmental engineering, Global Journal on Advances in Pure & Applied Sciences [Online]. 2013, 01, pp 657-664. Available from: http://www.world-education-center.org/index.php/paas

Chakraborty, J., Schweitzer, L.A. and Forkenbrock, D.J. (1999), Using GIS to Assess the Environmental Justice Consequences of Transportation System Changes. Transactions in GIS, 3: 239-258. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9671.00020