Chapter 1

Comments/Notes

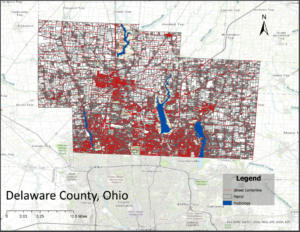

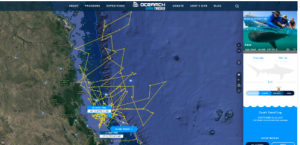

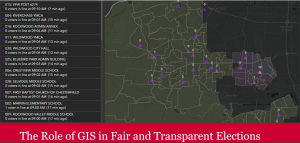

Since the time Esri Press first published the book in 1999, GIS has become more popular. There have been major advances in GIS software, like incorporating intuitive interfaces as well as more advanced mapping and analytical tools. Some of the most common geographic analysis tasks people do while doing their jobs are mapping where things are. One common task involves mapping the locations of the most and least common objects. Mapping the density. Finding what’s inside and nearby. Mapping changes. GIS analysis is a process for looking at the geographic patterns in the data you collect and at the relationships between features. To do this, you start by framing the question, and an example of this is, “How many people moved to Delaware, Ohio, in the past 5 years?” Some factors that influence the data are how it will be used and who will use it. When working with GIS, the type of data and features you are working with will help determine what method you will use. When collecting data, there are almost always two or three ways that you can collect the data. Some of the types of features that you can see on GIS are discrete features, continuous phenomena, and features summarized by area. Discrete features are when the actual location can be pinpointed. At any given spot, whether you can see the feature or not. Continuous phenomena like precipitation or temperature can be found or measured anywhere. Features summarized by area represent the counts of individual features within a certain area’s boundaries. There are two ways that the GIS can be represented: vector and raster. Vector is when each feature is in a row or table, and feature shapes are defined by x,y locations in space. Raster is when features are represented as closed polygons. There are types of attribute values: categories, ranks, counts, amounts, and ratios.

Questions:

How did spatial data scientists discover that GIS can be used for much more than building geodatabases and making maps?

Chapter 2

Comments/Notes:

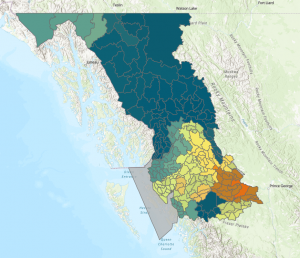

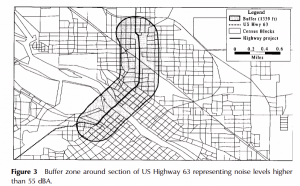

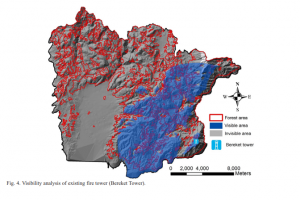

People use maps to see where and what an individual’s feature is located. When looking at the map, you can see the distribution of features on the map. Rather than at individual features, you can see different patterns that can help you better understand the area you are mapping. Mapping is important because mapping where certain things are can allow you to see where you need to take action or different areas that meet your criteria. Also, by looking at the different location features, you can begin to explore causes for the patterns you are seeing. Before you create the map, you need to make sure the features you are mapping have geographical coordinates assigned and optionally have a category attribute with a value for each feature. When assigning location, you need to make sure each feature has a location in the geographic location. When assigning category values, you need to make sure that each feature has a code that can identify its type. Many categories are hierarchical, with major types divided into subtypes. The GIS stores the location of each feature as a pair of geographic coordinates or a certain set of coordinate pairs that define its shape, like a line or area. When you make a map, the GIS uses the coordinates you input to draw the features using symbols you specify. Most of the time, mapping a subset is more commonly done for individual locations. When you are mapping an area that is large relative to the size of the features, using more than categories can make patterns harder to see. But when smaller areas are mapped, individual features are easier to see, so more categories will also be easier to see.

Questions:

When you are making maps or looking at a map, can you overlay two maps of similar areas to compare them both if made by two different people?

Chapter 3

Comments/Notes:

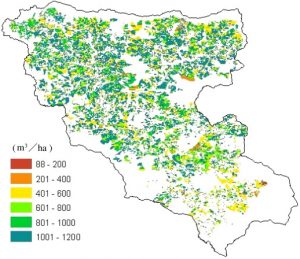

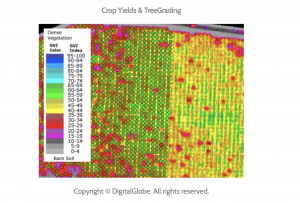

When mapping, people map the most and least because it is to find places that meet their criteria and take action, or it is to see the relationships between the different places. To be able to map the most and the least, you need to map features based on a quantity associated with each other. Mapping features based on the quantities adds an additional level of information that is beyond simply mapping the locations of features. When mapping, you need to know the type of features you are mapping as well as the purpose of your map, which will help you decide how best to present the quantities to see the patterns on your map. When mapping discrete features, they can be individual locations, linear features, or areas. Locations and linear features are most likely to be represented with graduated symbols, while areas are often shaded to represent quantities. Continuous phenomena can be defined as areas or surfaces of continuous values. Areas are often displayed using graduated colors, while surfaces are displayed using graduated colors, contours, or a 3D perspective view. Data summaries by area are usually displayed by shading each area based on its value or using charts to show the amount of each category in each of the areas. Once you have decided on how to classify the data values of your map, you will want to create a map that presents the information you have found to the map readers as easily or clearly as possible. Since GIS makes it easy to create maps and the database often has so much information, the temptation is to show more information than you actually need on your map.

Questions:

N/A