GEOG291 Introduction

Hello! My name is Panagiota Banti but people call me Naya! I am an international student from Greece and I am double majoring in Computer Science and Data Analytics. My favorite food is sushi and I love going to the gym and hanging out with my friends. On campus, I am also a cheerleader and part of the Computer Science and Programming Club.

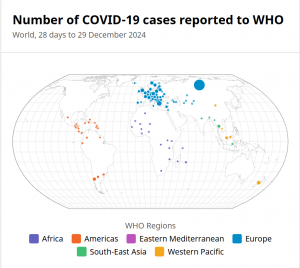

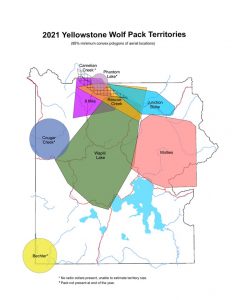

To begin with I don’t have any knowledge about GIS. This passage helped me understand a lot about GIS from its history to questions a tool like this might raise. The passage successfully explained the history of GIS and how it evolved to become an important tool in many different fields. GIS is used for mapping and not only. It analyzes cities, social trends, health patterns, and environmental issues. However, there are some issues concerning society that haven’t been discussed thoroughly.

This type of technology has many uses but it raises the question of what its true purpose is because it is used in different ways across various fields. GIS can be said that is shaped by a combination of social and academic ideas and its data is used to help with important decision-making. Therefore, we understandand analyze the world around us and GIS plays a fundamental role in our everyday lives without knowing it. I was fascinated by how many uses GIS has that we didn’t know of. I thought that GIS is solely used for environmental or geographical reasons and therefore, learning about all its uses is something that surprised me.

Something that I found interesting is the privacy concerns GIS raises data privacy and centralization of powerbecause GIS can track everything and keep private information. Even more concerning is the fact that there is no privacy safeguards for this issue.

Another interesting thing that I didnt know about is that GIS is something that younger people know already when coming to college and that shows again how important this tool is starting to be in our everyday lives, and the same goes in academia. There are still challenges in collecting and organizing data from GIS but this issue seems to be in progress.

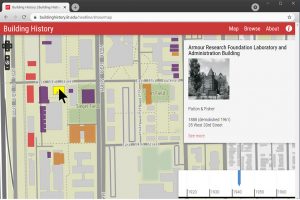

GIS Applications

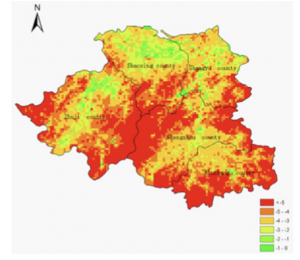

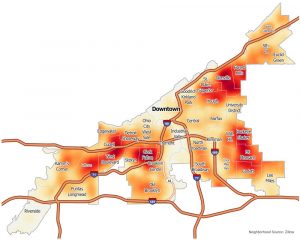

- Contaminated sites

GIS applications in contaminated sites are essential for, monitoring, and managing environmental contamination. Hazardous materials such as heavy metals, chemicals, radioactive substances. The research I found was how GIS protected people from contaminated water.

https://mcwec.org/2023/11/using-gis-technology-to-protect-people-from-contaminated-water-part-1/

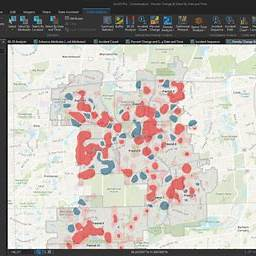

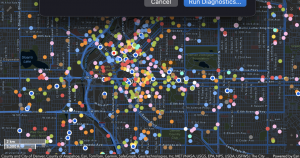

- Crime

GIS helps law enforcement agencies make data-driven decisions by giving them visual representations of crime trends which makes it possible for them to recognize patterns, distribute resources effectively, and create focused treatments.

https://crimetechweekly.com/2015/10/20/what-is-geospatial-crime-mapping/