Hopefully this works:

Geography 291: Geospatial Analysis with Desktop GIS

Module 1: 1/14/2026 to 3/3/2026, OWU Environment & Sustainability

Chapter 6:

Chapter 7:

Chapter 8:

Chapter 9:

Chapter 10:

Chapter 1:

Chapter 2:

Chapter 3:

Chapter 4:

Chapter 5:

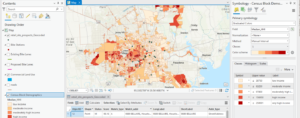

Mitchel Ch. 1: This introductory chapter starts off with defining GIS analysis as the process of looking at geographic patterns in your data and at the relationship between features. It discussed how we start the process of analysis by figuring out what information you need and the question you have at hand. It is important to take into consideration how the information will be used and who will be using it. The order of events to start is to choose a method of gathering your information, processing the data, and looking and reviewing the results. After you’re done if the data is not useful you can rerun it with different parameters. Geographic features can be discrete, continuous phenomena, or summarized by area. Discrete features are actual locations that can be pinpointed and the feature can be either present or not. An example of this is businesses – as individual locations, streams – as linear features, and parcels – as discrete areas. Continuous phenomena allows you to determine a value at any given location; for example precipitation or temperature. It starts with a series of sample points that are either regularly or irregularly spaced. GIS then uses these points to assign values to the area between the points, which is called interpolation. Summarized data represents the counts or density of individual features within area boundaries. We also learn that geographic features are represented by vectors and rasters. Vector models put each feature in a row in a table and the feature shapes are defined by x,y location in space. Continuous data and discrete features and data summarized uses vector models. Continuous numeric values and continuous data uses raster models. The chapter highlights that all data layers you use should be in the same map projection and coordinate system to ensure the accuracy of the results when combining layers. Then it moves into talking about attribute values: categories, ranks, counts, amounts, and ratios.

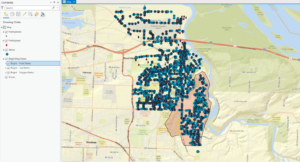

Mitchel Ch. 2: This chapter discusses different aspects of mapping and how they affect the maps. It goes over ways to make maps more efficient and how to effectively display the information you are trying to show. By looking at the different distributions of features on a map can help you see different patterns. Sometimes overlaying a lot of features and points to show patterns are effective, while on the other hand, making separate maps for different categories can make it easier for comparison. This is because it needs to be appropriate for the audience and the issue being addressed with the maps. When preparing the data you need to check that the features have geographic coordinates assigned to them because each feature needs a location in the geographic coordinates. Also, when you map features by type they need their own code that identifies which type it is in each feature. To add categories you need to create a new attribute layer in the data; many categories are hierarchical with major types divided into subtypes. When making the map you need to inform GIS what features you want to be displayed and what symbols to use to draw them. To map features as a single type, you draw all features using the same symbols. GIS stores the location of each feature as a pair of geographic coordinates or as a set of coordinates to define its shape. For example linear features are drawn by connecting many points. You can map features in a data layer or subset based on a category value, using a subset you have selected based on a category value. You can map features by category by drawing features using different symbols for each category value, this is stored in the layer’s data table. The chapter also goes over map scale and ways to make the map easier for views to understand, and or the way you change categories and change the way the readers perceive the information, which is extremely important.

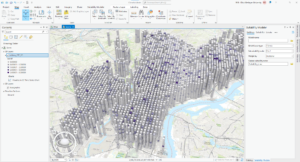

Mitchel Ch. 3: This chapter titled “Mapping the Most and Least” informs you about how doing both can help you find places that meet criteria and actions to be taken or emphasize the relationship between places. Mapping features based on quantities adds an additional level of information. By mapping this way it can help you decide how to best present the quantities to see the patterns on your map. Then the chapter goes into different types of features being mapped. Discrete features usually represent locations and linear features with graduated symbols, while areas are often shaded. For continuous phenomena areas are displayed using graduated colors while surfaces are displayed using graduated colors, contours, or 3D perspective view. Data summarized by area is usually displayed by shading each area based on its value or using a chart to show the amount in each category. It is important to understand the quantities you will be mapping to better present your data. Using counts and amounts allow to see the value each feature is given and shows you the actual number. Ratios show you the relationship between two quantities and are created by dividing one quantity by another, like averages, proportions, and densities. Ranks put features in order and can show realtice values rather than measured values. Examples are a scale with different colors saying excellent, good, fair, and poor. Classes group features with similar values by assigning them the same symbol, you can create classes manually or use a standard classification scheme. The different classifications schemes are natural breaks, quantile, and standard deviation. This chapter also talks about the importance of looking at outliers and how it might skew your results. You can put each outlier in its own class and use a special symbol for them. When creating a map you can you use graduated symbols, graduated colors, charts, contrours and 3D perspective views to show the quantities.

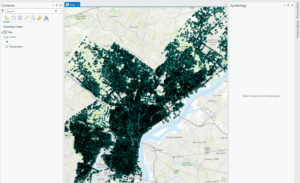

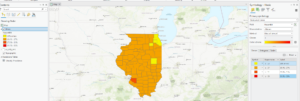

Mitchel Ch. 4: This chapter covers the idea of density. Mapping density can show you the highest and lowest concentration of a feature. This is helpful for identifying patterns. A density map allows you to measure features using a unoform areal unit, such as square miles, so you can see the distribution. This can be particularly helpful when mapping an area, such as census tracts or counties, which can vary in size. To show density you can shade different areas based on the density values. Also, you can map density features, like location of businesses or feature values, like the number of employees at each business. You can map density in a couple different ways: graphically, using a dot map, or calculate a density value for each area. When creating a density surface it is created in GIS as a raster layer. You should map density by area when you have data already summarized by area, or lines or points you can summarize by area. You should create a density surface when you have individual locations, sample points, or lines. When creating a dot density map you map each area based on a total count or amount and specify how much each dot represents. The larger the amount represented by each dot, the more spread out they will be. Also, you can change dot size to emohasize the patters. When a density surface is created in GIS it defines a neighborhood around each cell center, then it totals the number of features that fall within that neighborhood and divides that number by the area og the neighborhood; that value is assigned to the cell. When picking a cell size it needs to be appropriate for the graph, smaller cells will take more time process while larger cells can lose detail and make the pattern disappear.

My name is Jocelyn Weaver and I am an environmental science and geography major with a botany minor. I am from Hudson Ohio which is around Cleveland. I am a junior and on the track team on campus (I throw javelin). I like hiking and being outdoors, my favorite food is mashed potatoes, and I am on the student Envs board. I am excited to learn more about GIS and use it potentially in a future career.

-It is true, when I tell people I do research involving GIS, most people do not know what that stands for

-Interesting how the idea of overlaying came around in 1962 and was the original idea for GIS basis

-The article brings up multiple angles in which GIS is looked at by different people and how people categorize it like wether its quantitative analysis or an extension of mapping which is an interesting concept

-It interesting all the ways GIS can be used and applied, which people do not regularly think about like farmers and what you eat and where it comes from and how to get to your local supermarket

-Never heard the term “leap-frogging” before and the example of people in sub Saharan Africa never having a landline but having cellphones now

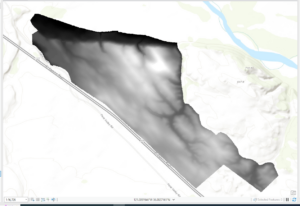

I looked up GIS storm water management and multiple articles came up using GIS and other data sources to predict and map land to show where storm overflow water would go. This article specifically talks of a new method USISM to simulate urban storm inundation. Due to urbanization and other human factors flooding is more frequent. To be able to find inundation quickly an urban storm-inundation simulation method (USISM) based on GIS is proposed. GIS technology is used to find depressions in the land and other data such as digital elevation model (DEM) to obtain flow order of the depressions.

Arc storm surge is a a GIS application that models data involving hurricane waves, surge models, simulating waves nearshore, and wave models and hydrodynamic models. This program involves pre and post processing tools to help spatial data and numerical modeling. Hurricanes cause immense costal flooding and damages and which these prediction models will be able to understand the events of a simulated hurricane storm surge.

Zhang, Shanghong, and Baozhu Pan. “An urban storm-inundation simulation method based on GIS.” Journal of hydrology 517 (2014): 260-268.

Ferreira, Celso M., Francisco Olivera, and Jennifer L. Irish. “Arc StormSurge: Integrating hurricane storm surge modeling and GIS.” JAWRA Journal of the American Water Resources Association 50.1 (2014): 219-233.