GIS ch1

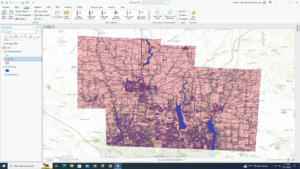

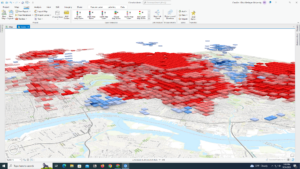

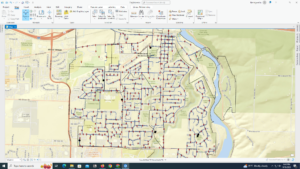

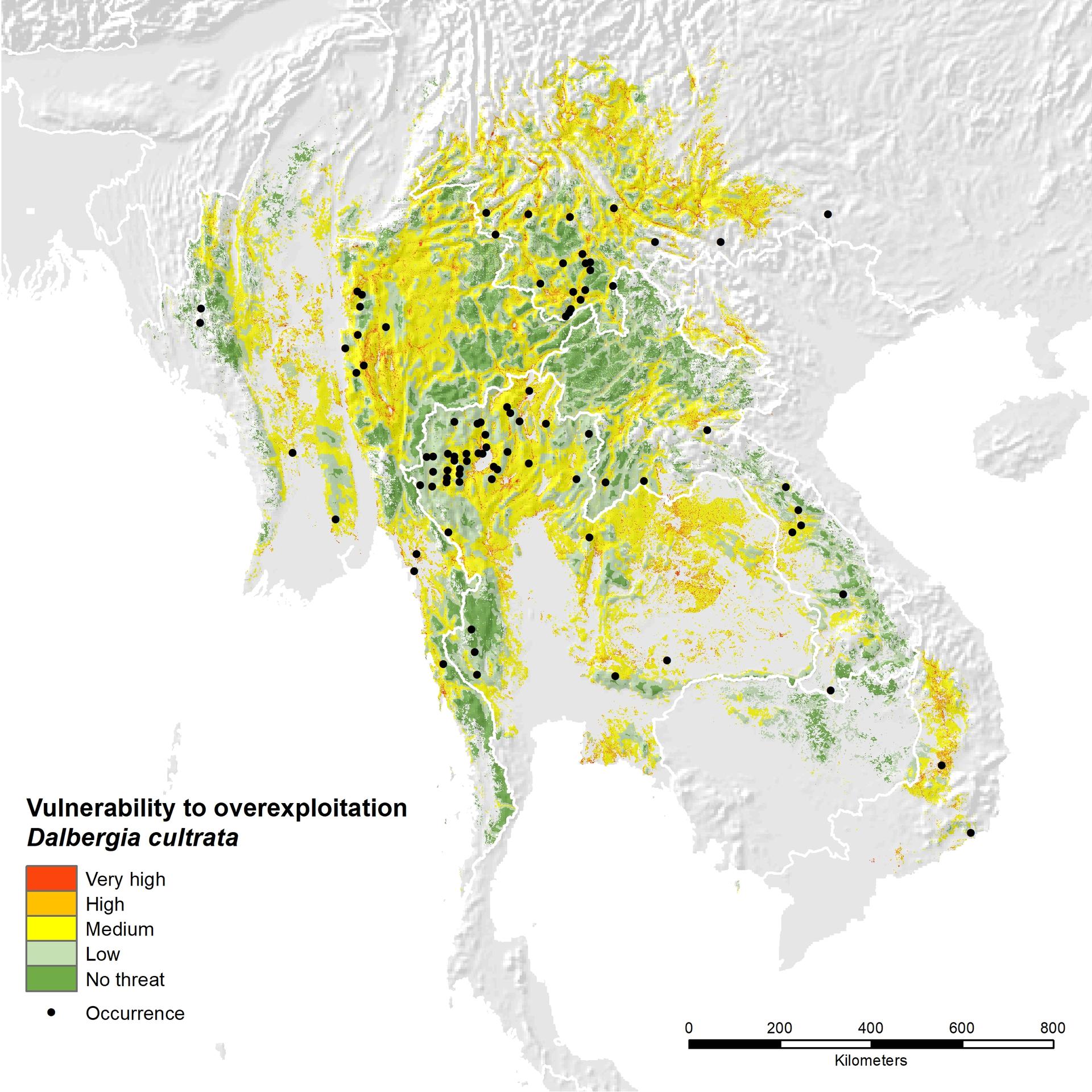

This first chapter broke down the basics of GIS. What to use it for, how to use it, and which options are best for depicting different types of data. A big part of this chapter was the introduction of vector models and raster models. Vector models are often coordinates and lines that are the summary of data tables. Vector models are especially useful for discrete data which are values more specific than the alternative continuous values. On the other hand, the raster model is more useful for continuous numerical values. Raster models are depicted as cells that can be combined side by side with other cells to show how the data connects or overlaps. Layers are more prominent and used more often in these models. Another key difference between raster and vector models is that raster is more scale sensitive. Distortion can happen in all models and all scales but it is most significant in raster models. To counter this, you can find the appropriate sale from the original scale and the minimum map unit. Between these two models, continuous categorical values can be used and seen in either. This also brings up the continuous phenomena. The continuous phenomena describes how certain analytical values can be found or measured anywhere.

Another important factor of GIS is layering. This chapter gave some good information on how overlaps can make tags for pieces of information which can then be used for layering.

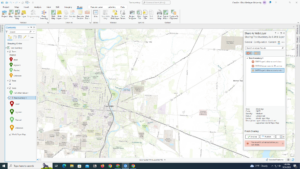

Towards the end of the chapter, categories, ranks, counts, and ratios show up. These are all attribute values that are important factors in GIS. Categories are values with a common aspect. Ranks are orders assigned to categories. Counts are total numbers. Ratios show the relationship between two or more categories. Categories and ranks are noncontinuous values because there can be the same value while counts and ratios are continuous values because they are completely unique.

GIS ch2

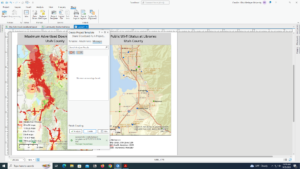

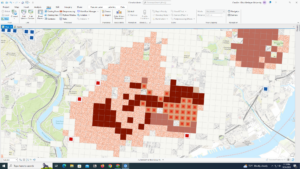

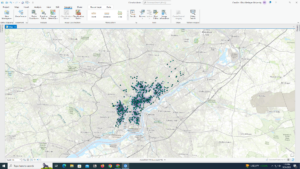

In this chapter, more of the mapping mechanics were thrown out there. Things such as category classifications, scales, and vector and raster models were revisited along with the addition of the use of subsets, grouping, zooming options, and colors or shapes of a map. From all of these other factors, chapter two explains the change of patterns. Patterns can be much more recognizable when you use a distribution of data instead of more individual sizes for the map. Using subsets can bring more detail to certain categories which could also bring out some unseen patterns. Similarly, zooming in or out can show us new things based on the original map scale like discussed in chapter one. For the sake of clarity, many large scale maps don’t use shapes for location points because with so many points it may be hard to recognize the shapes in clusters. In smaller scale maps, more colors and related categories can be used because there is less area to focus on so it will add detail without subtracting clarity. For this reason it is suggested to use no more than seven categories on large scale maps but if there are more, there is the option of grouping. This sometimes jeopardizes important information for the sake of clarity but can even emphasize already existing patterns that were not as prominent.

Chapter two made me excited to start thinking about ideas for my own GIS maps. With all of the examples being featured along with the first look into how we will be doing this unfamiliar task, my mind is stirring. A lot of these examples were crime based and from seeing all of them I feel like I have a pretty good basic understanding of crime patterns shown here. This gives me a sort of reference point for how I want anyone viewing maps that I may make to see them. Aiming for clarity along with detail and distinguishable patterns.

GIS ch3

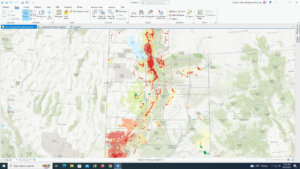

Chapter three is about being able to understand what you’re putting in a map and what purpose each feature has. This chapter also mentions these factors from an audience perspective along with an exploratory perspective. Either way, you start with determining certain types of quantities like the previously mentioned ranks, counts, and ratios. This time, there is an addition of averages, proportions, and densities used to present gathered data. Averages are used when there are not a lot of features in one area and a lot in another area and you need to find a connection between the two. Proportion is used to find part of a larger whole or break down a large scale into a smaller scale. Densities are used sizes in an area that have a lot of variety. Another important strand of terms is the ones used for creating classes. Natural breaks, quartile, equal intervals, and standard deviation. Natural breaks are classified by jumps in the raw data and are useful when data is not evenly distributed. Quartiles are classified by similarities in numbers of features (low to high) and are good for data that is evenly spread. Equal intervals are classified with even amounts of highs and lows. It is simple to understand and good for continuous data. Standard deviation is classified by distance from the mean which makes it good for comparing values to an average.

Other useful pieces of information in this chapter were what to do with outliers depending on the type of map you use and the types of features. Also, the use of raw data is interesting because a lot of times raw data is good to look at for lots of detail, but it does get overwhelming if presented to the audience who may not have as much previous knowledge on the topic represented in the map as whoever collected or used the raw data.

I found the section providing examples of all the map features and their advantages and disadvantages helpful because it pulled all of the beginning chapters together in a visual way. It also just summarizes a lot of the past chapters so I think I’ll be referring back to those pages later on in this course.