First Week

ArcOnline Exploring: I have previously logged into my arconline account in Dr. Krygier’s earlier GIS class (before the 191 and 192 modules). I enjoy working with ArcOnline and think it is a good addition to the desktop GIS software. I find it relatively easy to navigate and use to view and make maps. Every time I go on it I am surprised by how many tabs and different buttons/capabilities there are, and this time was no different. I’m excited to hopefully understand the function of all of these tabs at the end of the course.

Get Started: What is ArcGIS Online. Readthrough: I think one of the most exciting things about arc online to me is that you can work on maps collaboratively and virtually with other users and organizations. This is an incredibly powerful tool to connect people and to accomplish projects with people in far away locations. I read about this in the “Get Started” tab in the “Share and Collaborate” section and can see this being super useful when working with a professor or in a professional capacity and not having to go on a desktop machine or share drives/folders. I was interested in the app section of the read-through, because I haven’t had much experience with ESRI (?) apps beyond ArcOnline and ArcPro, so clicking through them on arconline was interesting. There is a large span of content/ industries covered by the apps, and it really highlights how diverse and powerful GIS can be. I was particularly interested in the GeoPlanner app, and a bit more research showed that it can be used to design and plan buildings and other structures in accordance with the geographic information of the area.

Getting Started Course(s): I had already completed the ArcGIS Online Basics course, so chose to do the “Basics of JavaScript Web Apps” because I am anticipating having to make a Web App for an independent study with Dr. Rowley and think this may be useful. My first impression is that using HTML format for web pages is familiar, because of work that I have done with Dr. Krygier in previous classes. That feels good and is making me excited about potentially being able to do this (the coding is a little scary). The section on software development kits (SDK’s) and introducing maps to online apps makes sense and I feel is applicable to what I want to do with Dr. Rowley.

Interesting ESRI online training: The “Get Started with ArcGIS QuickCapture” seminar seems interesting. It focuses on how you can use QuickCapture to take images and make them into data to be used in arc. I was interested in this because it includes “rapid data capture from moving ground or air-based vehicles” which could potentially include remotely sensed data. Another course of interest is the “Creating and Sharing GIS Content Using ArcGIS Online

“ because I am interested in being able to share maps that I make with other people. I think this might provide some insights on how to share maps in a variety of ways.

GIS Application Areas: Making interactive web maps using arc online. I know I’ve talked about it before but this website details how you can make these maps and post them online which is something I’m very interested in doing at the moment. It is a 13 page pdf tutorial of how to do this. This website details how to map flood risk areas with arc online. I think this is an interesting topic and is something that the remote sensing class worked on doing in ArcPro on the desktop machines. I think it would be interesting to see how the online software compares and if there are any major differences.

Second Week : Chapters 1 & 2:

My first impression reading chapter 1 is that the capabilities of Arc online are immense. There is so much powerful stuff that the software can do. It’s pretty amazing. Learning about the five main types of content supported by arc online, data, layers, web maps and scenes, tools, and apps, was really helpful and explanatory. I also found the attachments section, starting on page 17, very interesting because I have never been able to attach a picture of ppt or video to an Arc map before and this could be a super informative and useful addition to a map.

Chapter 1:

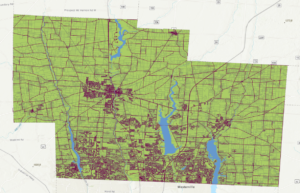

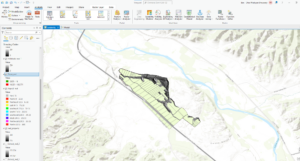

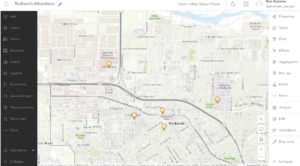

This is the Redlands attractions map from Exercise 1. It was kind of tedious to make with the new ArcOnline software but generally pretty straightforward and workable. The others parts of the chapter were also straightforward and easily completed when working slowly and methodically.

Chapter 2:

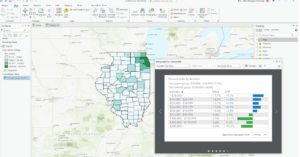

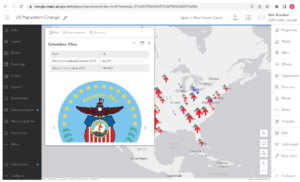

I wasn’t able to correctly code in a new expression in chapter 2 and so I didn’t have the growth rate (2010-2020) pop-up when I clicked on specific cities. The book’s description of the expression generator tab was different from what it actually looked like so this was kinda difficult.

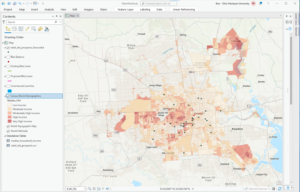

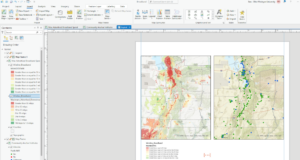

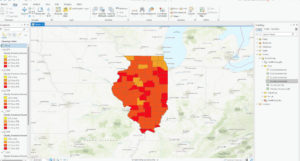

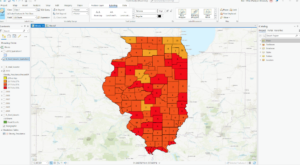

This is what my map looked like after 2.4. I couldn’t find the “sample chapter2 owner.gtkwebgis” so I was not able to do the tutorial for 2.5 and 2.6.

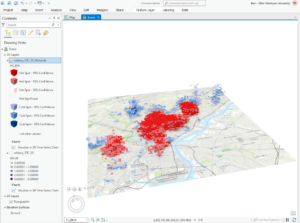

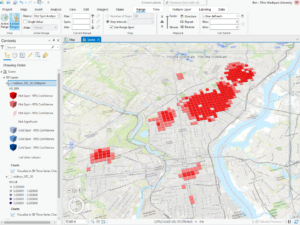

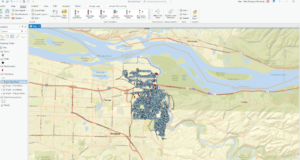

I can see the sort of techniques we used in chapters 1 and 2 being used with the Delaware data for the school districts. I could potentially see us generating a map similar to the map in chapter 2 with the Delaware county school district. We could also use the techniques from chapter 1 in order to make a similar map from subdivision data. Highlighting where all of the subdivisions are in Delaware County.