Chapter 1

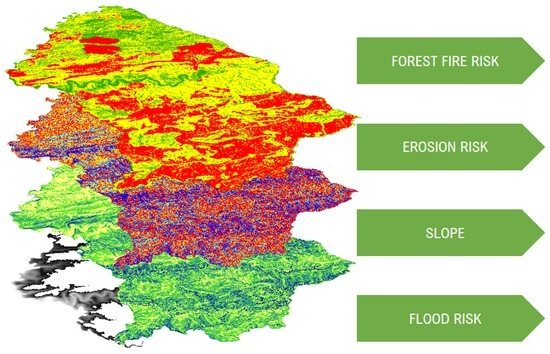

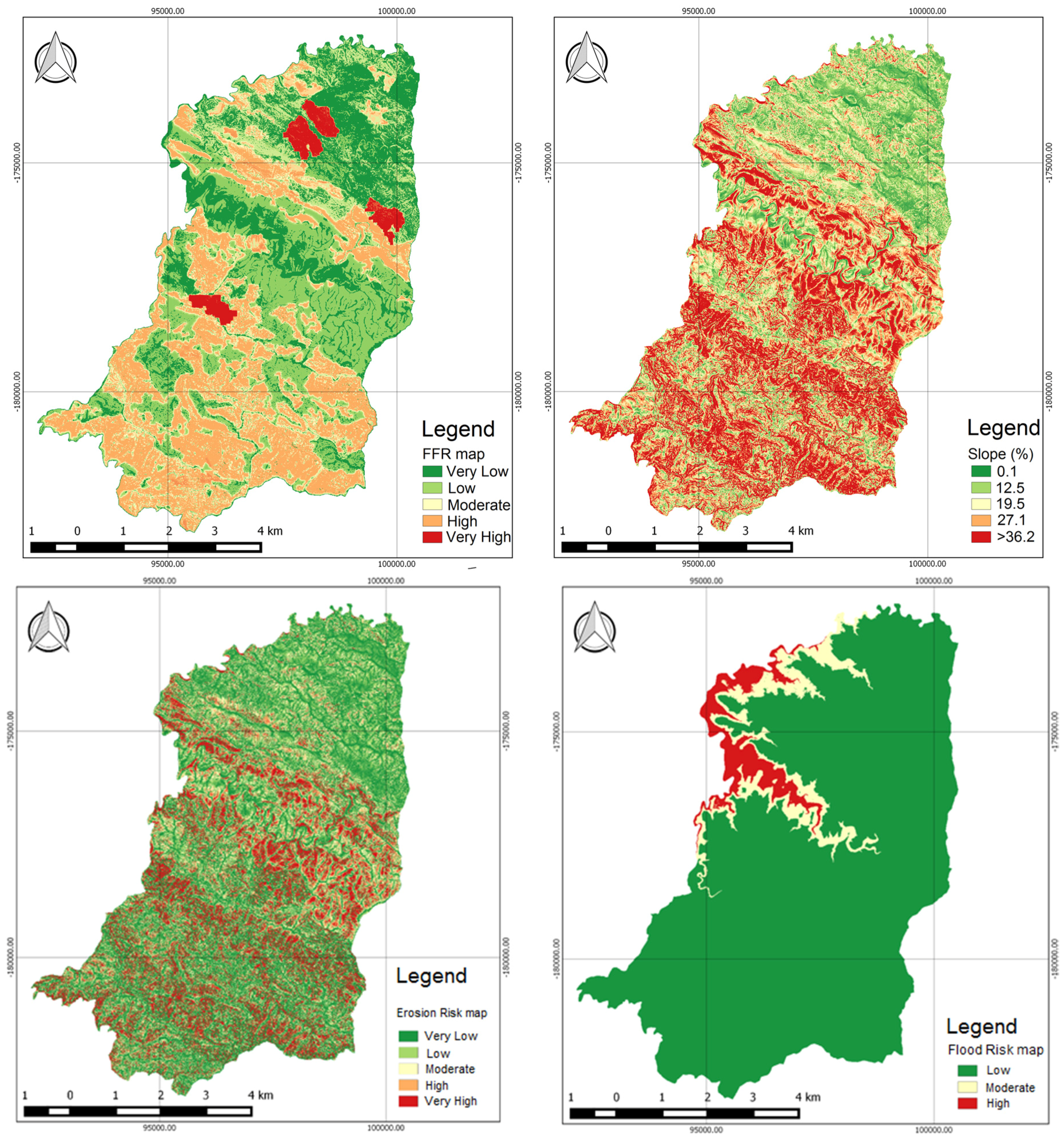

GIS, or Geographic Information System, is a process for looking at geographic patterns and features. This works by creating softwares and models to view data in a complex or simple way. To start, you have to decide the question you want to answer which will help in the next steps of determining the approach. Depending on the reasoning behind the question and the purpose of observing the data in this way will determine how complex or simple the visualizations need to be. After reading the first part of this chapter, it has helped me gain a better understanding of why someone needs to use GIS for their jobs. It also helped describe why more data would be needed and that getting more information can be as simple as adding new calculations into the software. Also, I appreciated how it explained the difference between using GIS for a quick study compared to a long, time-consuming one that could be used for a more official purpose. I found it interesting how the chapter mentioned that you want to find a way to represent your data clearly so that the intended viewers would be able to understand the information. I think it was also good to note that this can take many attempts to get to the final product and it is not a simple process. The features you include can be discrete, where the location gets pinpointed; continuous phenomena, where the data blankets the entire area being mapped; or summarized by area, representing data within area boundaries. Geographic features are additionally represented by either vector or raster. With vectors, each feature shape is defined by an x,y location. With raster, features are represented by a matrix of cells in a continuous shape. The representation used depends on what specifically needs to be shown with the data. When combining layers, the same map projection and coordination should be used to show accurate results when comparing relationships between information. This chapter did a great job explaining while also utilizing examples and pictures making it easy to understand. Finally, through using attribute values (categories, ranks, counts, amounts, and ratios) you can combine the numbers into a data set to then be able to use calculations.

Chapter 2

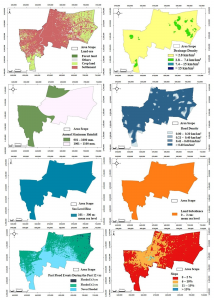

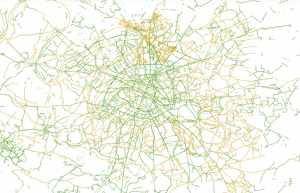

Deciding what to map with GIS is dependent on the question you are asking. By looking at the location of these features, we can then explore the patterns being shown. To find these patterns, the data should be layered within the map with different symbols. This connects back to the first chapter where it must have the same coordination so the relationship can be easily visualized. The use of the map created also is dependent on the audience. Extra information should be included in the map when the intended audience does not clearly understand the data or location. The chapter explains that when you prepare your data to create the map you should assign geographic coordinates and category values. This step helps ensure that your map will clearly show what information you are trying to inform others on. What I found interesting about this chapter is how customizable the software is. GIS allows you to tell it what features to display and how to symbolize them as well as storing the specific coordinates of your data points. While this concept seems complex, the chapter included photographs to help visualize what it is trying to explain with each type of map. GIS can be mapped in multiple ways, including dots, lines, or others depending on what your data is. For example, the chapter included lines for mapping streets, and points for mapping location of crime. The color can additionally be changed to allow for the overlap described in chapter one that lets the viewers see the relationship between the data. It also included that a rule of thumb is to have no more than seven categories because most people can only distinguish up to seven colors on a map. This is especially an issue when data is displayed in small scattered features. The main example the chapter showed was zoning maps and how much clearer it is to read with less categories. It gave an example of grouping categories in order to create less color difference while also showing the same information. In the zoning map example, it combines heavy industrial, light industrial, and mixed used industrial into one industrial category. The chapter included multiple more examples on how to choose colors, symbols, and lines when creating GIS to help get the point across in an easy viewable way. The clearer that the information is presented, the easier it is to view the patterns.

Chapter 3

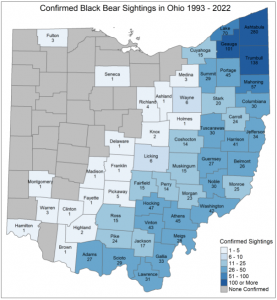

When using GIS, another component to think about is to map both the most and the least. This allows for them to find the places that meet their criteria and see the relationship between locations. Mapping quantities allows for another layer of depth beyond mapping location. To begin this step, the chapter explains that you first must consider what features you are mapping. One part I found interesting was that it explains your map should be created with the purpose in mind. When presenting the map to an audience more components need to be considered compared to if you are looking at the data yourself. Quantities on a map can be counts, amounts, or ratios. Counts and amounts show you the total numbers while ratios show the relationship between two quantities. This chapter also introduces using ranks. Ranks show relative values and can be useful when direct measures are difficult. An example I liked in the chapter was stating what portions of the trail had an excellent or good view compared to portions with fair, poor, or no data. Once the quantities are determined, the next step is dividing them into classes or giving each value its own symbol. Mapping individual values requires a lot more precision, yet can allow you to spot relationships in the raw data. I found it extremely interesting how it explains GIS is able to calculate mean and standard deviation when creating the map. It also explains how deciding classes is not just a simple process and it must consider outliers in data and how you want it to be presented. Additionally, you want to make sure it stays easy to read. This chapter did a great job of explaining the process of creating a map and including options and steps and the advantages and disadvantages of each. It also provided many charts, graphs, and examples similarly to the last two chapters. Towards the end, what I found most interesting was the inclusion of the Z-factor. The Z-factor increases the variation in the surface making the differences much easier to see without exaggerating. You can also include a light source to determine how shadows appear within the surface. What I found most interesting about this was the effect it gave the map and how big of a difference it made in the examples to be easily understood.