Week 6 Work:

Chapter 7:

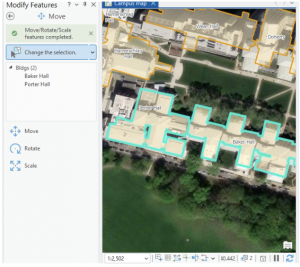

This chapter/ tutorial was actually a lot of fun to work with. It felt a lot like working in Adobe Illustrator, with making the point lines, and moving the features. I also felt very fancy using the Cartography tool, and “improving the aesthetic” of my map/ its lines. Learning how to edit, delete and move the buildings around was super cool. This is extra useful in the world we live in today, with construction and deconstruction always affecting/ moving locations and landmarks. It was interesting to think that no matter how “good” a map might be, there can still be aspects of it that are warped between the system and ground map. Being able to fix that distortion can be an extremely invaluable tool. Creating features is also very useful when starting a map from scratch, or if the project doesn’t include the needed feature class. Because this chapter dealt with a lot of permanent modifications, it included good advice to keep an unedited version of whatever map you’re working on in case of any errors. That way you can just go back to the original file and start the map over again. Using a style of system work that mimics the work of Architects and professional location planners at the end made the assignment feel very professional. Like, it ran us through what the professionals do, giving us an idea of what to expect if any of us wish to go to that level.

Chapter 8:

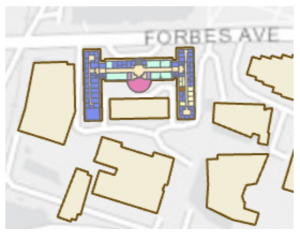

This chapter went very local, working primarily with Zip Codes and Counties. Using geocoding to map the charts of zip codes and counties, the chapter bridged the gap between chart data and actual geographic locations, inputting them into analyzable features on the maps. This chapter introduced Match Scores, something that I am still trying to understand a little bit more. Essentially, the match score shows the percentage of accuracy of an address when evaluated with a reference. Around 85%-98% is usually an acceptable score range, but in some situations it’s ideal to try to have a perfect 100% match. I did have a few issues with this chapter when trying to Rematch Addresses. Whenever I would try to click the map to set the rematch, I would continue to get pop-ups and the rematch selection wouldn’t actually register. I turned off the pop-up setting from the map (temporarily) and it seemed to bypass the issue. As I stated before, I believe that longer tutorials are more beneficial to my learning process- and this was heightened using chapter 8. As this chapter only actually has 2 assignments built into it, they both build off of every step followed in the textbook. If something was missed, or incorrectly done, the entire assignment would be messed up and needed to be redone. This was a bit annoying, but in the end the repetition definitely aided my understanding of the topics taught in this chapter.

Chapter 9:

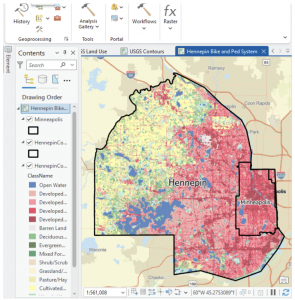

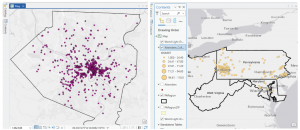

Learning about and setting up buffers was something that was briefly recapped in some of the much earlier chapters, so I had some initial knowledge on them. My first thought when working with them was that they’re bubble letters for feature plots! These bubbles were quite fun to set up, and I can visualize a lot of reasons why someone would use them on a map- like finding a specific feature within a distance from certain features, and gathering data on what’s outside these zones as well. It’s very neat that the buffers can have multiple layers of distances applied to a single feature set at the same time. And although I actually like the “target” look on the map, and how it visibly shows the change in distance on the plot, I can understand that there might be reasons to make a single “multiple ring” buffer containing both blended together. A small note for the future, that using Optimized seed in the Multivariate Clustering tool is the setting that should be used when making your own projects/ data. This entire chapter was extra visually appealing for some reason, the colors used as symbology on the features fit well, and I absolutely love the way the map looks with the Locations-Allocation assignment with the lines diverging from the “ideal” location points. That entire assignment was fascinating as well, how the system was able to calculate the best locations of pools from the data collected and accessed. It was a great representation of the ability of GIS to manipulate datasets to create purpose driven maps. The system works for real world problems, using analysis to work out relationships between features/ points, and provide a simple answer to questions asked about data.

Week 7 Work:

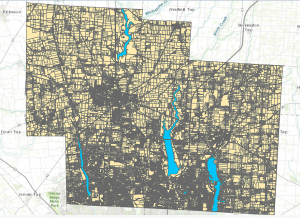

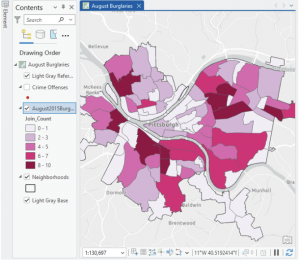

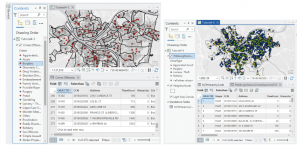

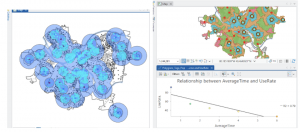

The Delaware City maps have been downloaded, and inserted onto a created GIS Pro map for the final project map. I moved the maps around adjusting their map display from the drawing order to see which layering was best, featuring all the needed datasets. The Parcel map is very interesting to explore, with how much detail it has within its data and display. I generated ideas for my final project and evaluated each dataset’s information.

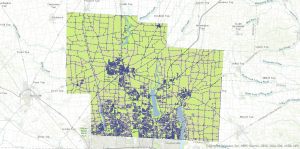

The Parcel map is managed daily by the Delaware County’s Auditor GIS Office, with data kept by the Delaware County Recorder’s Office. It shows clearly defined boundaries of land plots and features from all around Delaware. It is packed to the brim with every single road, building and section of land, complete with their IDs, data, and building names. I will note that the map looks like it could be a little bit off, with some features not in the correct location on the map, or it could simply be the way I have it layed out creating this illusion. This dataset is key to working on the “What’s Inside?” section of the final project, as it requires the data being gathered to be set from within, or inside a parcel of Delaware land.

The Hydrology map shows all major waterways of the Delaware County, and was made in July of 2022 with no updates since then. This dataset could be useful if inspired to work with runoff into waterways, or a specific project with water. However, it may not be entirely useful for other areas of mapping besides acting as a location identifier.

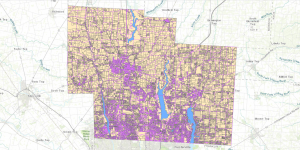

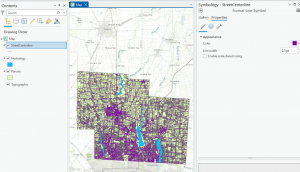

The Street Centerline map is a highly adaptable map with many ways to use it and displays exactly what it sounds like, all the public and private roads located within the Delaware County district. Made from data collected by The State of Ohio Location Based Response System (LBRS), the map remains updated daily for most aspects except for the monthly 3-D model updates. This map is great for landmarking, and making the map easy to understand if reading it for specific locations. This map can be useful for a number of things ranging from emergency response maps and ranges, to appraisals and accident reports.