My name is Lane Hughes. (It will appear as Lane Elliott until this gets fixed by the registrar). I just switched majors from Business Management to Environmental Studies. I found that business didn’t align with my values. I am a commuter student. I work at Cackler Tree Farm. My sister also attends OWU and my brother will be next year.

My biggest takeaway from the reading is that I am among those that did not recognize the GIS acronym or how it affects my daily life. Chapter one of Schuurman’s work explains pervasive GIS is in modern life, but also how it began. In its origins, people were reluctant to use it or acknowledge its usefulness. GIS is used in so many different ways that it is hard to define. The idea that GIS is simply a computer program is what Schuurman wants us to get away from. GIS has shaped much of the current world. Policies are made based on information obtained from GIS. The beginnings of GIS were based on industry needs. It is important to remember that although GIS is computerized, it is still reliant on human input. Therefore, it may not be error free. GIS can also be thought of as an academic discipline to be studied. Schuurman believes that because there is room for error and so many different purposes, GIS should be used with an understanding of its vast abilities, but also its limitations. GIS is extremely influential in our world today. One part of this chapter I enjoyed was the story of how one of the early computer cartography systems was developed. It is wild that something that became so fundamental began by two guys who happened to sit next to one another on a plane and share a common need for a system such as this. After reading this, I still have a lot of questions. One question is if GIS can be objective, since data and classification is determined by human input? Additionally, if there is a lack of objectiveness, what is misrepresented and how would one know?

GIS Application One: https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/a08e4636ef6945b0a1a93820bcb334ca

Nesting Sea Turtles on a Changing Caribbean Island shows interactive maps where turtle nesting sites are located and how these locations have changed over time. Research collected helps management practices. This is valuable because it helps with decision-making and influences policies.

GIS Application Two:

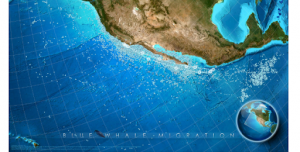

This application walks through the GIS project of tracking Pacific blue whales on their migration. ArcGIS Pro is used for this.

I completed the quiz!

Introduction:

Introduction: