Chapter 1: Introducing GIS Analysis

This chapter begins by briefly introducing the uses of GIS and defining GIS Analysis, which is looking for patterns between geographic features and the relationships between them. This can be done by creating/ using a map or overlapping multiple layers to see differences that may not be readily apparent.

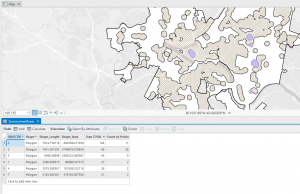

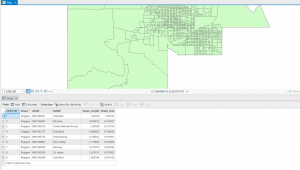

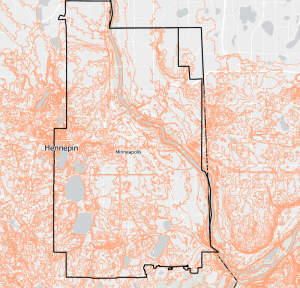

The next section describes the first step in the process, which is Framing a Question. Knowing what information you want from an analysis is key to creating this question, and you need to determine the audience (yourself, your peers, a professor) to successfully set up your methods and frame the question more accurately. The book also describes the different features that you will encounter while doing GIS Analysis, those being Discrete features, Continuous phenomena, and features summarized by Area. Each has it’s own specific use case, with Discrete features being single points on a map, Continuous being variables that are present across the whole area but change (such as temperature or Elevation), and summarized features show counts within a boundary, such as population within county lines.

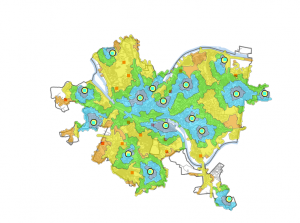

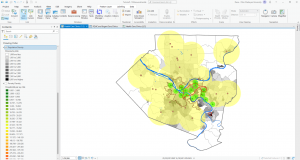

The book then shows us two different ways of visualizing data using ArcGIS, those being vector and raster modeling. Vector is good for showing discrete features and summarized features, as they typically use one layer, and Raster is good for showing continuous categories or numbers. However, either render can be used to show any feature. I found this section fairly interesting, as it seemed for continuous data, there was not too much of a difference between vector and raster models, however, there were large differences when discrete and summarized data were done on both models. The next section, dealing with Attribute values, seemed fairly easy to understand, especially after doing work on Rstudio Cloud for the past few semesters, and the final section seems to be nearly identical to R.

Chapter 2: Introducing GIS Analysis

The main focus from this chapter, in my opinion, is to make your maps as accurate and as easy to read as possible. The chapter starts with numerous examples of how and why you may need to show others your maps, emphasizing the fact that you will need to know this information. I appreciated that each mapping strategy had its pros and cons described, as it showed that none of these methods are truly useless, just have trade offs.

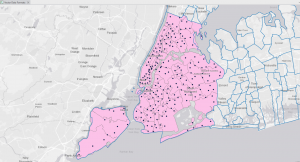

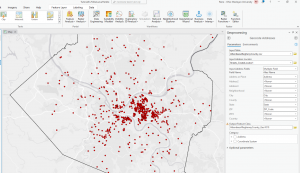

Every one of these strategies was a different variation on creating different layers to show information, by subsetting the data in different ways. With discrete or continuous data, you can highlight a certain subset by making it a strong, striking color, and the other subsets different background colors. If you have one map that has every data value on it, it can become clustered and hard to look at. Because of this, it can be very helpful to make multiple maps that each show a different subset, as well as one map which combines them all.

Another important piece of information that the book emphasizes is to use no more than 7 categories at once, as this can also be overwhelming. If you have more than seven features, you can group certain categories together that have similar traits. Your use of symbols is also important when designing your map. Colors are much more distinguishable than symbols, so they should have a higher priority. However, when using Linear features, you should use different widths rather than colors as that is more easy to see. Text labels can also be used to label your different categories. The last section of the chapter talks about how you can use different features to understand more about the feature you are looking at. For example, if looking at patterns of growth over an area, elevation can be key to finding the origin of these patterns.

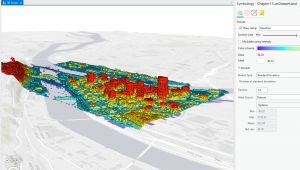

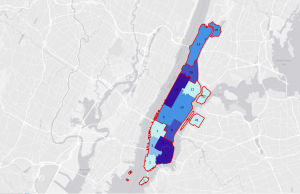

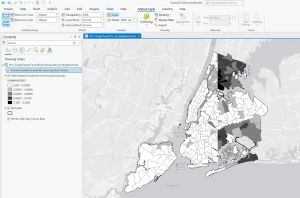

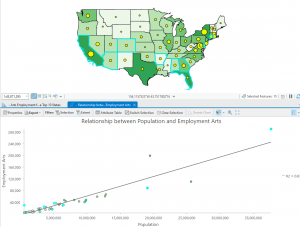

Chapter 3: Mapping the most and the Least

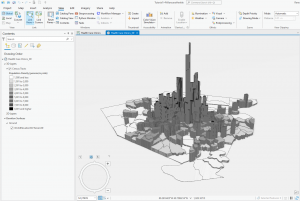

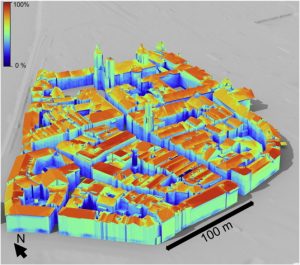

This chapter starts out by explaining why mapping minimum and maximum values in data is important. This is because it can show weak points in current systems, and where we might need to improve. There are multiple ways of recording these values, those being “Counts and Amounts,” which are the number of features, “Ratios,” which show the relationship between quantities, and “Ranks,” which order quantities from high to low (and assigns a value). These features can then be grouped into classes, which simplify and group amounts to prevent your data from getting too cluttered. To create these classes, you can either do it manually or use a classification scheme. You only need to do it manually if you are trying to find features suiting a specific criteria, such as a specific percentage or something specific to your area of study. If not doing it manually, you can use the aforementioned classification schemes. Natural Breaks (Jenks) find large jumps in data values and group the data between those lines. Using a Quantile divides groups so that each one has an equal number of features (Essentially having small amounts of large data and large amounts of small data). Equal Intervals makes the difference in groupings equal across the data (Regardless of size or quantity). Finally, there is standard deviation, which groups data by its distance from the mean. When choosing between these schemes, you have to take into account the distribution of your data and if you are trying to find a difference or similarity between. The book also discusses what to do with Outliers if you find them, as some schemes cause these outliers to heavily skew your results. Next, we are taught how to visualize our data on a map. We have five options; Graduated Symbols, which are good for discrete data but can be hard to read if too abundant, Graduated Colors, which are good for continuous and area data, but do not always accurately represent the difference in data, Charts, which essentially have the same pros and cons as the symbols, Contours, which are good for continuous phenomena but does not show individual features well, and 3D perspective views, which have the same pros and cons as Contours. You need to know which schemes to use to make your maps statistically accurate and how to use these map types in order to effectively display our data.