Data Inventory:

Zip Code: Contains all of the zip codes that fall (either completely or partially) within Delaware County. These parcels were created in 2005 according to property addresses, likely to ensure that properties were not split across zip codes.

Street Centerline: This data depicts the center of the pavement of all public and private roads in Delaware County to give a fair approximation of street routes throughout the county. This street system is called the Ohio Location-Based Response System (LBRS) and is heavily used by ODOT and emergency services. Street segments are measured from vertex to vertex.

MSAG: The Master Street Address Guide (MSAG) delineates townships and municipalities in Delaware County. Most townships are simple geometric rectangles, but the municipalities are irregularly shaped. Some municipalities are also their own townships, and they are located inside of other townships, as is the case with Sunbury Township located inside of Berkshire Township.

Recorded Document: These are records that do not match up with the subdivisions that currently exist on the Delaware County map. They include records of vacations, cemeteries, road centerline surveys, and utilities easements.

Survey: This dataset is a collection of the locations of all recorded land surveys in Delaware County more recent than Old Survey Volumes 1-11. There is a pretty high density of land surveys all throughout the county, except over bodies of water and in parks like Alum Creek State Park, Delaware State Park, and the Dover Recreation Area.

GPS: This dataset displays the shapefile of GPS monuments, or metal disks in the ground that mark latitude and longitude and serve as reference points. These monuments were established between 1991 and 1997.

Parcel: This dataset is incredibly detailed, showing land parcels in Delaware by ownership. Contains extensive information on each property, such as the address, current owner, sale history, and number of rooms.

Subdivision: This dataset contains subdivisions and condos in Delaware County. (These types of housing are typically higher-density residential areas.) Most subdivisions appear to be concentrated around the town of Delaware or the southern part of the county.

School District: All the school districts in Delaware County are displayed in this data set. Similar to the Zip Code data set, some small portions of school districts that mostly fall within adjacent counties are included.

Tax District: The tax district dataset appears to line up similarly to the MSAG data set but includes a few more divisions. Most of the tax districts around municipalities are shaped irregularly and are even sometimes nested shapes within the more geometric townships.

Annexation: This dataset shows annexations in Delaware County. They are concentrated around towns like Delaware, Sunbury, Powell, and Westerville.

Township: Shows all of the townships in Delaware County. Very similar to the MSAG dataset.

Address Point: This dataset uses LBRS to show all registered addresses in a shapefile. The point on the map is located in the centroid of the building.

Municipality: This dataset contains the municipality parcels that are noticeable in the MSAG and Township datasets.

Condo: Condo polygons are shown in this dataset. They are pretty small and well-dispersed, which, when compared to the Subdivision dataset, leads me to believe that Delaware County has lots more houses in subdivisions than condos.

Precincts: Delaware County voting precincts line up pretty well with township and municipality parcels but are divided within into much smaller areas.

PLSS: This dataset contains Public Land Survey System (PLSS) polygons, most of which are near perfect squares. However, the west side of Delaware County comprises more irregular PLSS polygons.

Delaware County E911 Data: This dataset uses an LBRS system of Address Points and is used in particular by 911 Emergency Services. Other uses include appraisal mapping, geocoding, reporting accidents, and managing disasters. This is measured in terms of US Military and Virginia Military Survey Districts.

Farm Lot: Contains all farm lots (as measured by military districts). Many are different shapes: square, long and thin, uniform rectangular, or irregular (as in the western and central parts of the county).

Building Outline (2021, 2023, 2024): Contains all building outlines in Delaware County. Very reminiscent of a Google Maps view. Each of the three databases was updated in its respective year.

Dedicated ROW: ROW stands for Right-of-Way, which is a type of easement, so it shows accessible street routes in the form of line data. It appears that streets that are not included as ROW routes are in private subdivisions or similar areas.

Railroads: The dataset highlights railroads running through Delaware County, and it appears that most of them run north-south.

Original Township: Displays boundaries of Delaware County townships prior to division by tax districts. Consists of 18 original townships. The eastern portion of the county has rectangular parcels, and the western portion’s parcels are more irregularly shaped, which is consistent with other similar datasets.

Map Sheet: A map sheet is just a map that is part of a larger map series. The data appears to show data at the sub-municipality or sub-township level. The smallest parcels are clustered around the cities of Delaware and Sunbury, and in the southern portion of Delaware County.

Hydrology: Contains the portions of all *major* waterways in Delaware County. Many small ponds and lakes on the map do not appear to be counted in this dataset.

ROW: Just like the Dedicated ROW dataset, this contains all line data of street rights-of-way in Delaware County.

Delaware County Contours: Contains two-foot contours showing the topography of Delaware County. This data was updated in 2018. It is in the form of a downloadable geodatabase.

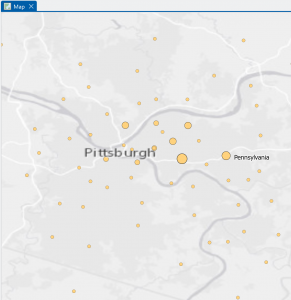

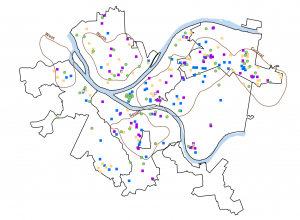

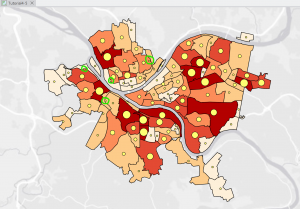

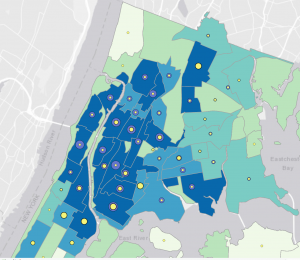

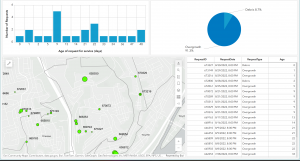

Map:

Figure 1: Delaware County Parcels (yellow), Street Centerline (green), and Hydrology (blue) layers.

Once I remembered I had to use the Add Folder button to add my files into the Catalog pane, it was smooth sailing making this map!