Hello! I’m Kheya Datta, I’m a 3rd year B.S in Biology with a minor in ENVS. Here’s a silly little drawing of me that I drew because I dont have any good photos of myself:

I did the Syllabus Quiz and read the reading.

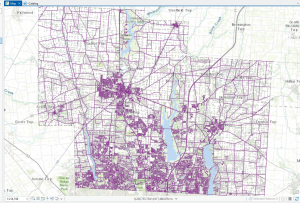

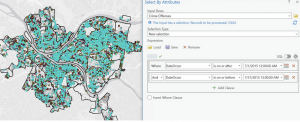

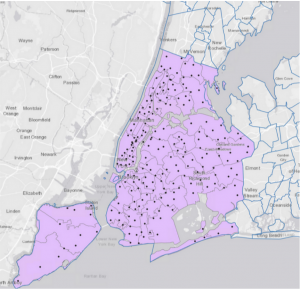

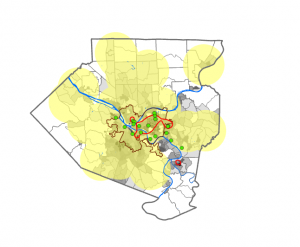

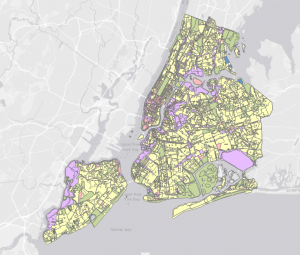

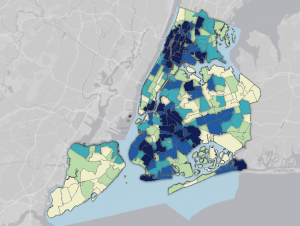

This introductory chapter starts by talking about the recent boom of GIS; when in the past GIS was only particularly useful to a select group of Geographers, now its used worldwide by all sorts of people from Police to Starbucks. It then discusses GIS’ history from analog to digital. The discussion of the history reminds me of my Mother; she is a Geography Masters, and partially due to the times and partially due to studying in India, she only knows analog style GIS. Then it discusses various predecessors to the modern GIS systems we know today. GIS appears to have been based around Quanitative methods of previous years, and lead to a revolution within this form of methodology in ways I’m excited to learn more about in the upcoming semester. Next it discusses GIsystems vs GIscience. GIsystems seems to me to be more useful for the everyday person; I’m sure someone studying something with GIS doesn’t want to particularly worry about GIS being faulty, and GIscience seems more useful for people trying to input their own data within GIS for deep-delves into research, beyond what is already available. It then goes into spatial data and then who uses GIS and for what. They discuss a lot of city planning and road building in this section, which fascinates me. My limited experience with GIS is solely in the physical geography, specifically hydrology amongst rivers, so it’s interesting to learn how GIS is used in the urban side of things as well. The mention of how GIS gets its data does make me wonder how GIS has been used in a political light, especially in our day and age.

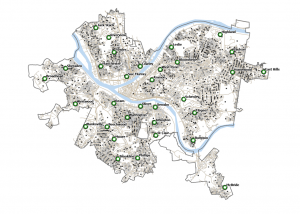

I’m really interested with Harmful Algae Blooms with my work, so I’ve found the NOAA Harmful Algae Blooms website for perusing. HABSOS can be used to predict upcoming Harmful Algae Blooms in the Gulf of Mexico (if it blooms last year it’ll probably bloom this year) and for the tech savvy consumer it could be a very good source for if there’s currently a harmful algae bloom. One of the things it tracks is Microcystins, a really bad toxin, so if a beach-goer sees thats high they can make the safe decision to not go.

NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) (2014). Physical and biological data collected along the Texas, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida coasts in the Gulf of America as part of the Harmful Algal Blooms Observing System from 1953-08-19 to 2024-03-25 (NCEI Accession 0120767). NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. Dataset. https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/archive/accession/0120767. Accessed 8/21/2025.