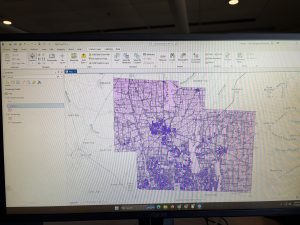

Zip Code: Contains all zip codes within Delaware County, Ohio. Published and updated monthly.

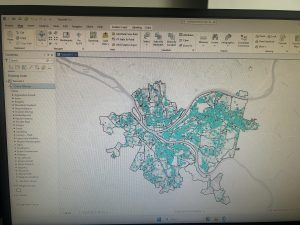

Street Centerline: Depict center of pavement of public and private roads within Delaware County, Ohio. Updated on a daily basis for all fields but the 3-D fields which are updated on an annual baiss, and is published monthly.

MASG: Stands for Master Street Address Guide, and is a representation of the 28 different political jurisdictions in Delaware County, Ohio.

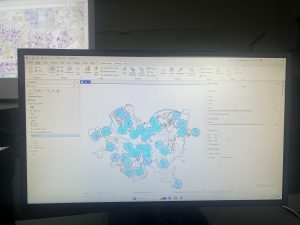

Recorded Document: Consists of points that represent recorded documents in the Delaware County Recorder’s Plat Books, Cabinet/Slides and Instruments Records which are not represented by subdivision plats that are active. Documents such as; vacations, subdivisions, centerline surveys, surveys, annexations, and miscellaneous documents within Delaware County, Ohio. Updated on a weekly basis, and is published monthly.

Survey: A shapefile of a point coverage that represents surveys of land within Delaware County, Ohio. Surveys are found in documents in the Recorder’s office and the Map Department. The dataset is updated on a daily basis and is published monthly.

GPS: Identifies all GPS monuments that were established in 1991 and 1997. Dataset is updated on an as-needed basis, and is published monthly.

Parcel: Consists of polygons that represent all cadastral parcel lines within Delaware County. Dataset is maintained on a daily basis, and is published monthly.

Subdivision: Consists of all subdivisions and condos recorded in the Delaware County Recorder’s office. The dataset is updated on a daily basis and is published on a monthly basis.

School District: The dataset consists of all School Districts within Delaware County, Ohio. The dataset is updated on an as-needed basis, and is published monthly.

Annexation: The dataset contains Delaware County’s annexations and conforming boundaries from 1853 to present. Dataset is updated on an as-needed basis once an annexation has been recorded within the Delaware County Recorder’s office. It is published monthly.

Township: The dataset consists of 19 different townships that make up Delaware County, Ohio. The dataset is updated on an as-needed basis and is published monthly.

Tax District: This dataset consists of all tax districts within Delaware County, Ohio. The data is defined by the Delaware County Auditor’s Real Estate Office, and data is dissolved on the Tax District code. The data is uploaded on an as-needed basis and is published monthly.

Address Point: A spatially accurate representation of all certfiied addresses within Delaware County, Ohio. The layer provides the capability to reverse geocode a set of coordinates to determine the closest valid address and is intended to provide 911 agencies with information needed to comply with Phase II 911 requirements. The dataset is updated on a daily basis, and is published once a month.

Municipality: The dataset contains the municipality parcels that are within the MSAG and Township datasets

Condo: Consists of all condominimum polygons within Delaware County, Ohio that have been recorded within the Delaware County Recorders Office.

Precincts: Consists of Voting Precincts within Delaware County, Ohio. Maintained by the Delaware County Auditor’s GIS Office under the direction of the Delaware County Board of Elections. Dataset is updated on an as-needed basis and is published as-needed by the Delaware County Board of Elections.

PLSS: Consists of all the Public Land Survey System (PLSS) polygons in both the US Military and the Virginia Military Survey Districts of Delaware County. Created to facilitate in identifying all of the PLSS and their boundaries in both US Military and Virginia Military Survey Districts of Delaware County. The dataset is maintained on an as-needed basis where new surveys have been recorded, dataset is updated on an as-needed basis and is published monthly.

Delaware County E911 Data: The database uses the Location Based Response System (LBRS) and is used in 911 Emergency Response. The dataset is updated on a daily basis, and is published monthly.

Farm Lot: Dataset consists of all the farmlots in both the US Military and the Virginia Military Survey Districts of Delaware County. Dataset was created to facilitate in identifying all of the farmlots and their boudnaries in both US Miltary and Virginia Military Survey Districts of Delaware County. Dataset is maintained on an as-needed basis where new surveys have been recorded.

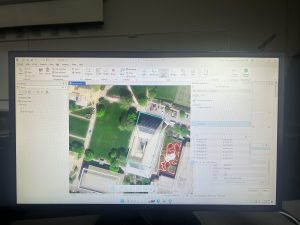

Building Outline (2021, 2023, 2024): Consists of all building outlines in Delaware County. Each of the three databases are updated within their respective years.

Railroads: Allows a user to view the locations of railroads that lie within Delaware County.

Dedicated ROW: Consists of all lines that are designated Right-of-Way within Delaware County, Ohio. This data is line data that is created through the daily updates of Delaware County’s Parcel data. Dataset is updated on an as-needed basis, and is published monthly.

Original Township: Displays boundaries of Delaware County townships prior to divison by tax divisions affected their shape.

Map Sheet: Dataset contains all map sheets within Delaware County, Ohio. Consists of 360 records.

Hydrology: Dataset consists of all major waterways within Delaware County, Ohio. Data was enhanced in 2018 with LIDAR based data. The dataset is uploaded on an as-needed basis and is published monthly.

ROW: A type of easement (right-of-way) that shows accessible street routes in the form of line data.

2024 Aerial Imagery: 2024 3in Aerial Imagery Flown Spring 2024. Published on September 25, 2024 at 7:45 PM EDT.

Delaware County GIS Data Extract Web Map: Web map used in Delaware County GIS Data Extract application that allows users to extract Delaware County, Ohio GIS data in various formats.

2022 Leaf-On Imagery (SID File): 2022 Imagery 12in Resolution, published on September 14 2022 at 1:42PM EDT

Delaware County GIS Data Extract: Allows users to extract Delaware County, Ohio GIS data in various formats. Published June 8 2020 at 6:23 PM EDT.

Delaware County Contours: 2018 two foot contours for Delaware County, Ohio in file geodatabase format. Published April 9, 2020 at 9:51AM EDT.

Street Centerlines — DXF: The LBRS Street Centerlines depict the center of pavement of public and private roads in Delaware County, Ohio and was collected by field observation

Auditor Logo: The logo of the Auditor’s GIS Office in Delaware County

Fall Background: The background for different GIS data

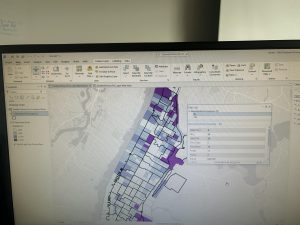

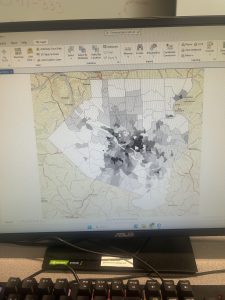

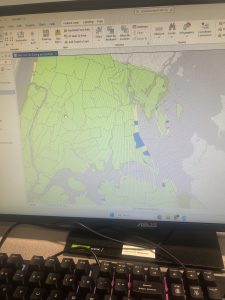

Here is my map that shows all three layers: Street Centerline, Hydrology, and Parcles: