Hello! My name is Gabrielle Plunkett and I am a senior biology major. A fun fact about me is that I have a cat named Finn who lives in my dorm with me.

I had never heard of GIS before coming to college, and if I did I didn’t recognize what it was. It interests me that they refer to GIS as a “scientific approach” due to the many different ways it can be used. It reminds me of when I took my animal behavior class and we discussed how there is no definition for the word behavior. It seems within this article people also define GIS in a myriad of ways. The term “black box” seems very fitting for GIS as many seem unsure about the legitimacy of these programs. However, as they gain more knowledge and the systems become better established people stop questioning the legitimacy. Since I didn’t know anything about GIS I also didn’t know there were different types. GISystems seem to be an identity of GIS while GIScience seems to be the theory that underlies the GISystems while still being its own identity. GIS seems to primarily focus on the system and hardware as a whole. To me, GIS seems to be taking a simple question and then asking it in multiple ways while forming digital entities, models, graphs, etc. so that it can be visualized. It also seems that every step of GIS has been disagreed upon such as the definition of spatial objects. I’ve read about John Snow’s mapping of Cholera before but never realized his map was a form of GIS. Seeing how GIS started from paper and pencil to the development of visualization to now is incredible. It does not surprise me that GIS quickly became widespread. Seeing a visual image of data is easier than just numbers for me, as I am more of a visual learner. I’m hoping I learn more about the different ways to use GIS and eventually get a better understanding of what exactly it does by doing it.

GIS and Crows

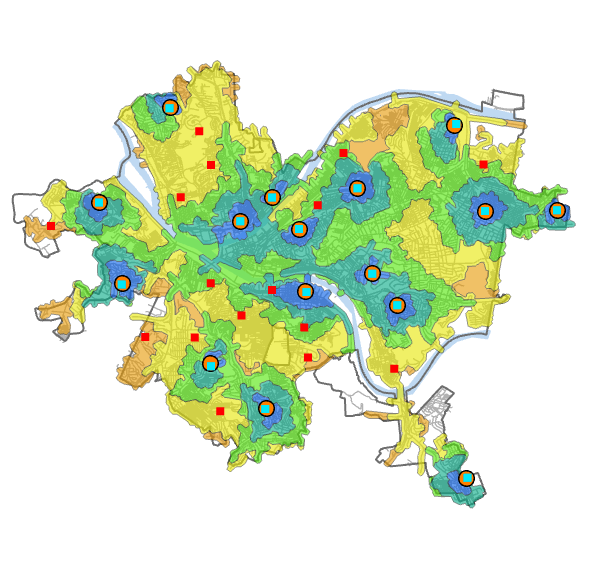

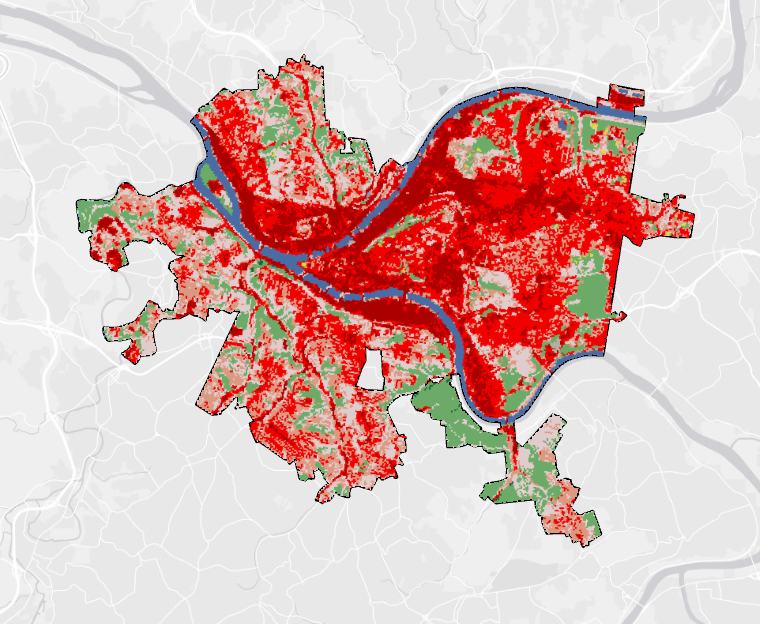

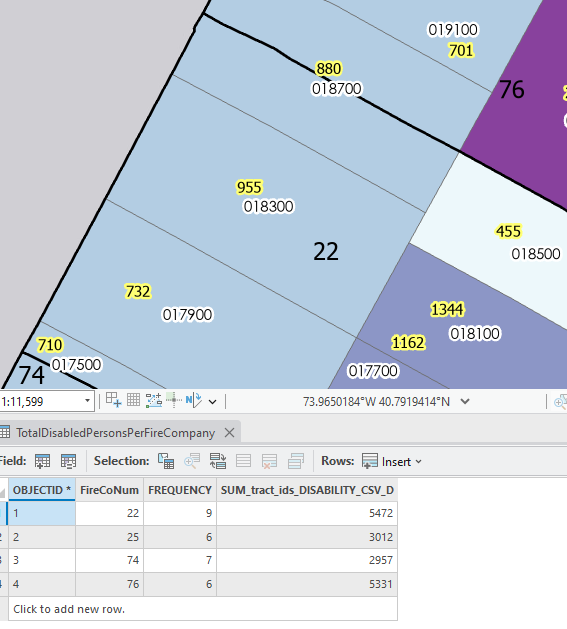

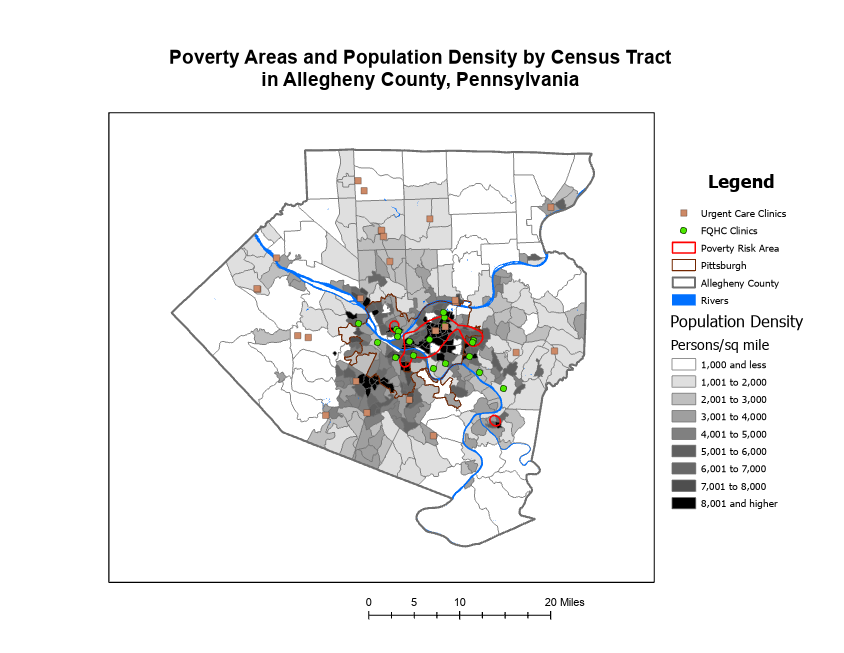

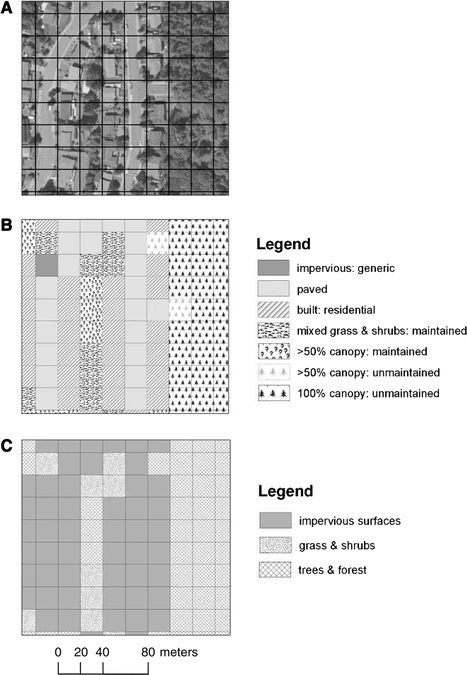

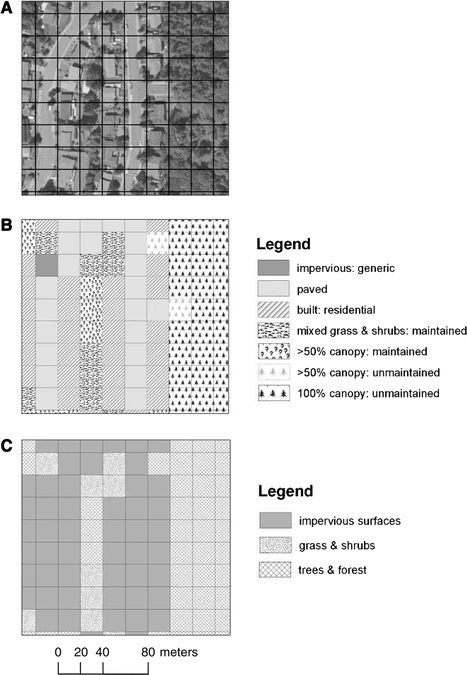

I’ve noticed a lot of crows on campus so I decided to see what I could find involving GIS. One use of GIS is the tracking of the type of land cover of American Crows. This figure shows the use of ArcGIS in creating grids to signify the different land cover/land use classifications of the study sites. The article studied the fine-scale characteristics of developed landscapes that may help explain the growth of crow populations in urbanizing areas.

Source: American Crows in an urbanizing landscape

In another article studying the dispersal rate of Juvenile American Crows, researchers used a program called RAMAS GIS to simulate the population growth of the crows and then put it into a model to visualize it. They used it to model two populations “urban” and “non urban”. This interested me because I have most likely looked at a simulated population model and didn’t realize it was done using GIS. There was no show model or figure for this section.

Source: Dispersal by Juvenile American Crows