Chapter 4

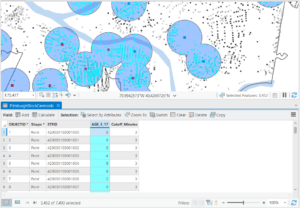

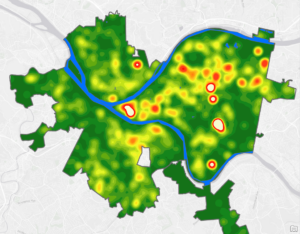

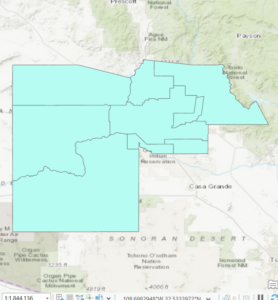

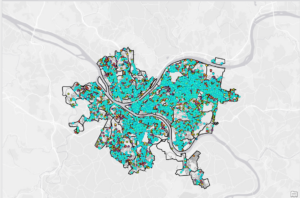

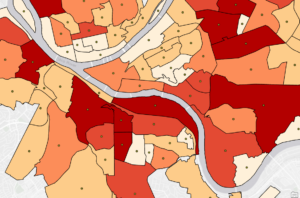

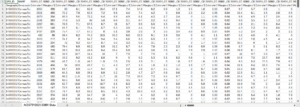

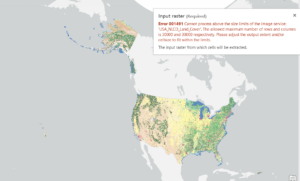

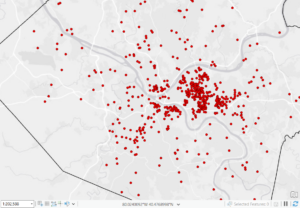

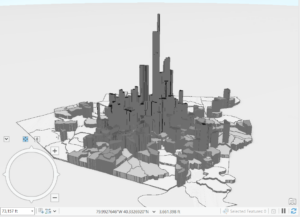

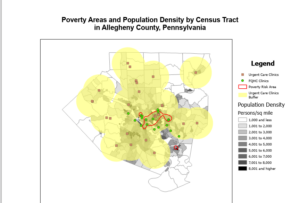

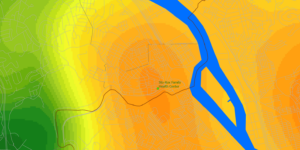

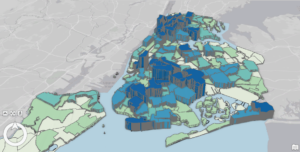

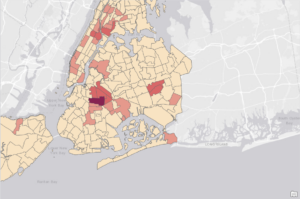

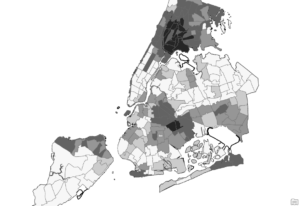

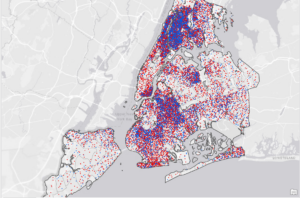

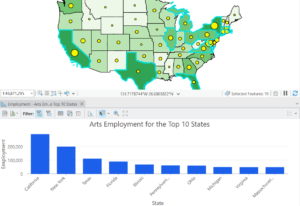

The main focus of chapter four is about ‘density’, and how to map the density of features. Other questions looked at are why map density is important, deciding what to map, different ways of mapping density, mapping density in a defined area, and creating a ‘defined’ surface. The higher the density of something, the higher the values are. For example, the correlation between density and high values can show areas of business, population centers, and areas of crime. The chapter also asks if you want to map explicitly features, or the values of said features, with the chapter using businesses in a given area vs employees in a given area, both on the same map. The chapter also lists two primary ways to map density. The first way is by ‘defined area’ or a dot map. Each dot on said map represents a specified number of features, and the closer the dots are together, the higher the density of features in that area. Then there is mapping by density surface, which is referred to as a ‘raster layer’ though what a raster is is not explained. In a density surface map, each cell gets a density value based on the number of features within the cell. As opposed to defined areas, density surface maps provide the most detailed information but also require the most effort to create. The chapter also details how to calculate the density values in defined areas depending on the type of map. Calculations can also show the features closest to the center of the cell. Chapter 4 also emphasizes the importance of the units used depending on the map type and what is measured.

Chapter 5

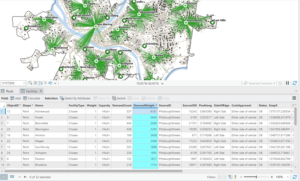

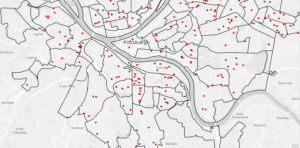

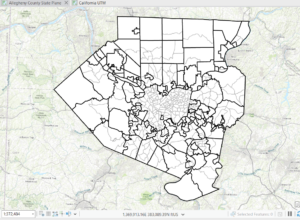

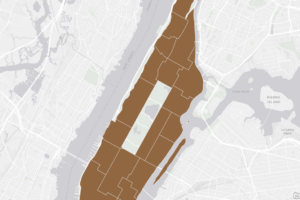

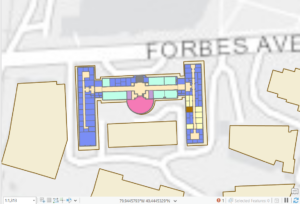

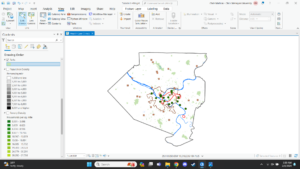

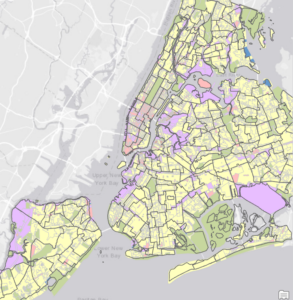

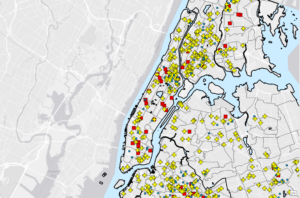

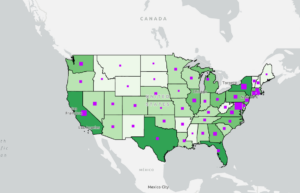

The main focus of the fifth chapter of Mitchell details what is on the inside of certain areas of map. The layout is the same as other chapters and like chapter three it seems to go on for a while, repeating a lot of information. Chapter 5 also focuses on defining the analysis of a map, different ways of finding what’s inside the map, how to draw areas and features, selecting features within a given area, and the overlaying of areas and features. One reason Mitchell gives to map inside is to know whether to ‘take action’ or not, giving examples of a district attorney monitoring drug related arrests in proximity to a school. The chapter also talks again about discrete and continuous features which I will admit I had forgotten existed until reading this part in the chapter. Mitchell details the information needed from an analysis, be it a list, count, or summary. In addition to the information needed, the chapter also goes over if you should include or exclude areas which are only partially included or excluded in the map. Key in the chapter are the three ways of “finding what’s inside”. By drawing areas and features you can see which features are in and outside of the area, and all that is needed is a dataset containing the boundary of the area and another dataset containing the features of the area. The second method is selecting key features in the area in order to obtain a summary or list of features in an area or group of areas, or for finding things within a certain distance of features. The final method is to overlay both the areas and features, which can be used to find which features are in different areas or finding out how much of said feature is in one or more areas.

Chapter 6

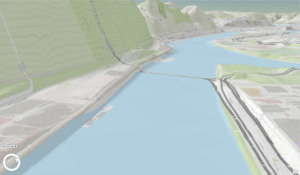

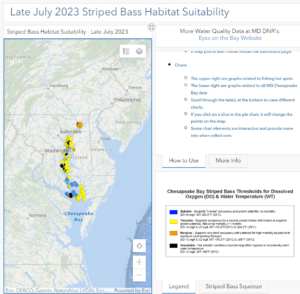

The main focus of the sixth chapter is “finding what’s nearby”, or as explained, letting you see what is within a set distance of a feature, allowing you to monitor events in an area. The chapter also focuses on reasons for mapping what’s nearby, using straight-line distance measuring, measuring distance over a network, and calculating costs over geographic surfaces. This is again where the book starts to lose me with mentions and examples of calculations given that I am not good with numbers in the slightest, but I digress. One reason Mitchell gives for mapping what’s nearby is for emergency situations, specifically using an example of a fire chief knowing the distance of streets within a three minute distance of a fire station. Mitchell also asks if you’re measuring what is nearby as distance or cost, which is another confusing aspect. Despite reading the section over again, it still doesn’t make sense how you can map cost over a geographical area. Another question of measuring is if you are measuring a flat plane using the ‘planar’ method or are you taking the curvature of the earth into account. The second method is substantially more difficult given that the curvature of the earth is not only uneven, but distorts maps and how they are viewed. For example, looking at the sizes of countries on a globe compared to their actual size on a flat plane. Measuring “what’s nearby” is outlined in three different ways, those being straight line distance which is exactly what it sounds like and is good for creating boundaries. The second method is distance over a network which is good for finding things within travel distance. The third method is cost over a surface, which I again don’t fully understand so I won’t try to explain or summarize it. Overall while parts of the reading are still interesting, I feel it becomes repetitive and tends to drag on much longer than it needs to.