Final Project Data Summary-

Zip Code: Data set containing all zip codes within Delaware County, Ohio. Data is published monthly.

School District: A data set that consists of all School Districts within Delaware County, Ohio. It is updated on an as-needed basis and is published monthly.

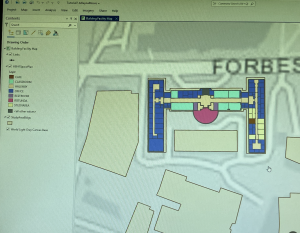

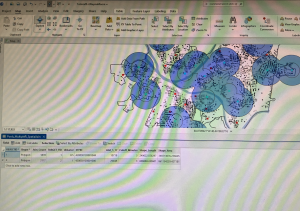

Building Outline (2021, 2023, 2024): Data sets consisting of all building outlines in Delaware County. These are separate datasets corresponding to each year provided.

PLSS: Data set consisting of all the Public Land Survey System (PLSS) polygons in both the US Military and the Virginia Military Survey Districts of Delaware County. This dataset is maintained on an as-needed basis, where new surveys have been recorded, and is published monthly.

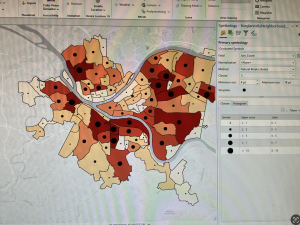

Township: A data set consisting of 19 different townships that make up Delaware County, Ohio. The dataset is updated on an as-needed basis and is published monthly.

2024 Aerial Imagery: Collection of images. 3in Aerial Imagery, Flown Spring 2024. Publish date is September 25, 2024, 7:45 pm.

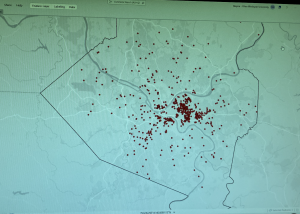

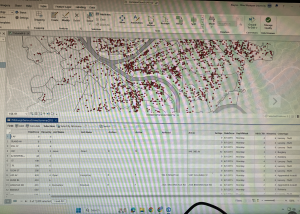

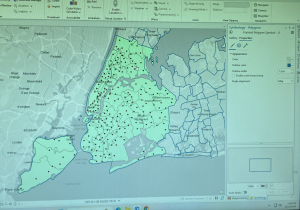

Delaware County E911 Data: Address Points data set that is a spatially accurate representation of all certified addresses within Delaware County, Ohio. In particular, the State of Ohio Location-Based Response System (LBRS) Address Points. Used to do appraisal mapping, geocoding, report accidents, and manage disasters.

2121 Imagery (SID File): File used to summarize images of Delaware County from 2021.

Original Township: A dataset that consists of the original boundaries of the townships in Delaware County, Ohio, before tax district changes affected their shapes.

Recorded Document: A dataset that consists of points that represent items that do not match up with the subdivisions that are currently active on the Delaware County map. Documents such as vacations, subdivisions, centerline surveys, surveys, annexations, and other miscellaneous documents within Delaware County, Ohio.

Precincts: A dataset that consists of Voting Precincts within Delaware County, Ohio. It is updated on an as-needed basis and is published by the Delaware County Board of Elections.

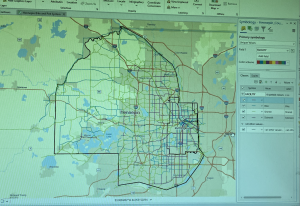

Dedicated ROW: A data set that consists of all lines that are designated Right-of-Way within Delaware County, Ohio. line data that is created through daily updates of Delaware County’s Parcel data.

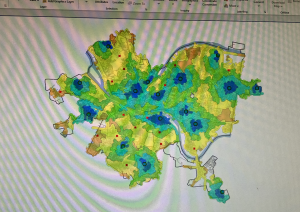

Delaware County Contours: 2018 Two Foot Contours for Delaware County Ohio in File Geodatabase format. Published April 9, 2020 at 9:51 AM. last updated on October 12, 2021 at 10:43 AM.

Building Outlines – DXF: Data consists of an image of specific building outlines in Delaware County using CAD drawings. Last updated on May 15, 2023, 7:04 PM.

Address Points – DXF: Dataset that uses LBRS to show a spatially accurate placement of addresses within a given parcel in Delaware County, or registered addresses in a shapefile. With Address Points indicating the location of the building centroid.

Street Centerlines – DXF: The LBRS Street Centerlines depict the center of pavement of public and private roads within Delaware County. Data was developed from data collected by field observation of existing address locations

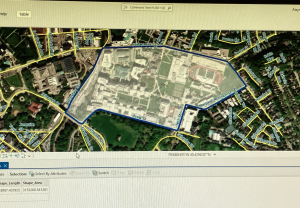

Parcel: This dataset consists of polygons that represent all cadastral parcel lines within Delaware County, Ohio. It contains information like current owner, sale history, address, and number of rooms.

Street Centerline: Dataset that uses LBRS to depict center of pavement of public and private roads within Delaware County. Data was developed from data collected by field observation of existing address locations.

Condo: A dataset that consists of all condominium polygons within Delaware County, Ohio that have been recorded with the Delaware County Recorder’s Office.

Subdivision: A data set that consists of all subdivisions and condos recorded in the Delaware County Recorder’s office. Is updated on a daily basis and is published monthly.

Tax District: A data set that consists of all tax districts within Delaware County, Ohio. Defined by the Delaware County Auditor’s Real Estate Office, and is dissolved on the Tax District code. Data is updated on an as-needed basis and published monthly.

Address Point: A dataset that uses LBRS to provide a spatially accurate representation of all the certified addresses within Delaware County. Is updated as-needed daily and published monthly.

Map Sheet: A dataset that consists of all map sheets within Delaware County, Ohio

Farm Lot: A data set that consists of all the farmlots in both the US Military and the Virginia Military Survey Districts of Delaware County. Created to facilitate in identifying all of the farmlots and their boundaries in both the US Military and the Virginia Military Survey Districts of Delaware County.

Annexation: A data set that contains Delaware County’s annexations and conforming boundaries from 1853 to the present. Is updated on an as-needed basis once an annexation has been recorded at the Delaware County Recorder’s office.

Survey: (A shapefile) point coverage that represents surveys of land within Delaware County, Ohio. These surveys are found in documents in the Recorder’s office and the Map Department.

2022 Leaf-On Imagery (SID file): 2022 Imagery 12in Resolution. Published on September 14, 2022, 1:42 PM

Hydrology: A dataset that consists of all major waterways within Delaware County, Ohio. Was enhanced in 2018 with LIDAR-based data. Is updated on an as-needed basis and is published monthly.

GPS: A dataset that identifies all GPS monuments that were established in 1991 and 1997. Is updated on an as-needed basis and is published monthly.