Chapter 4

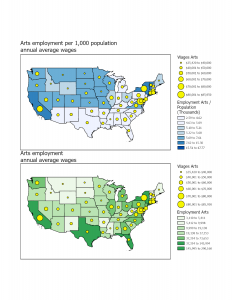

This chapter really made me think about how much more there is to GIS than just putting points on a map. One of the main things I took away was that it’s not enough to just know where something is—you also need to know what’s inside an area and how it’s distributed. At first, this seems simple, but the chapter made it clear that summarizing data can be tricky depending on whether it’s discrete or continuous. For example, counting animal nests is different from summarizing rainfall across a region. That distinction really stood out because it made me realize that even small details about the type of data change the approach entirely. I also liked the part about percentages and densities. Mapping totals can be misleading if areas are different sizes, which reminded me of what we talked about in the last chapter. If you don’t standardize the data, the map can exaggerate or hide patterns. I didn’t think about it much before, but even a small change in how data is summarized can completely change the story a map tells. Another thing that stuck with me was how tables, charts, and maps work together. A table can give exact numbers, but a map shows patterns more visually. Deciding which one to use really depends on the question you’re asking, which goes back to the idea that GIS is as much about thinking as it is about tools. Overall, this chapter made me see GIS as a way to organize complexity. It’s not just about showing locations—it’s about understanding patterns and relationships.

Chapter 5

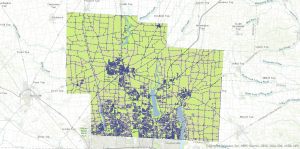

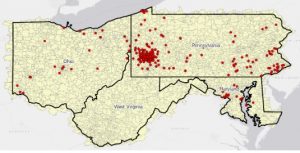

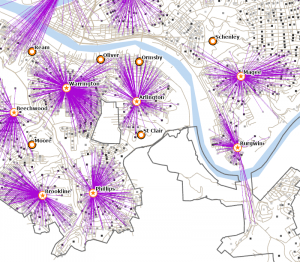

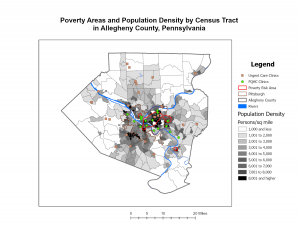

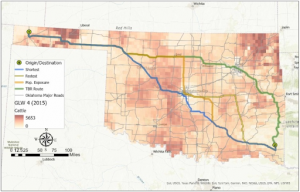

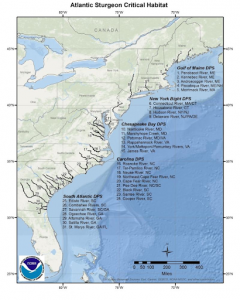

The reading for chapter 5 got me thinking about how “near” isn’t always as simple as it sounds. Distance can mean so many things—straight-line, travel distance, or even time—and choosing the wrong one can totally change your results. I never really thought about that before. The chapter explained that defining nearness is one of the first decisions you have to make in a GIS analysis, and that really stuck with me. I liked the discussion on buffers because it’s simple but powerful. Creating a zone around a river or road seems easy, but choices like how big the buffer should be or whether overlapping buffers merge can make a big difference. It reminded me again that GIS isn’t automatic—every step involves interpretation. Another part that stood out was straight-line distance versus network distance. Straight-line is faster, but it doesn’t always reflect reality. For example, animals or people usually can’t move in a perfect straight line, so network distance gives a better picture. This made me realize that picking the wrong method can give misleading answers, even if the calculations are correct. Overall, this chapter showed that proximity analysis is about understanding relationships, not just measuring space. It made me think about how this could apply to endangered species or habitat studies, where knowing what’s nearby can inform decisions about conservation. This chapter took the idea of distance further by showing that distance isn’t always about how far apart two points are—it’s also about cost. I thought this was really interesting because two places could be physically close but take a long time to get between because of terrain or obstacles. That idea made me think about animal movement, human travel, or even conservation planning. The concept of a cost surface really stood out. By assigning different “costs” to different areas, GIS can figure out the easiest path or total effort needed to get somewhere. I liked this because it’s like GIS is simulating the real world, not just showing it. It also made me realize that cell size matters—a smaller cell gives more detail but takes more computing power, so there’s always a trade-off. Another thing I noticed was how important it is to set limits on distance or cost. Without boundaries, the analysis could cover the whole area and give way too much information, which can get overwhelming. It reminded me again that GIS isn’t just about making maps—it’s about asking the right questions and making decisions that matter. Overall, this chapter made me see GIS as more than mapping. It’s a tool for modeling real-world problems and thinking about movement, accessibility, and patterns. It made me wonder how I could apply this to tracking wildlife or studying how roads affect habitats.

Chapter 6

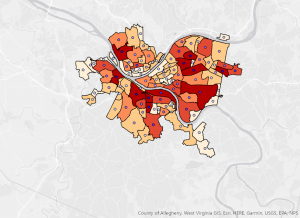

The last section emphasized how mapping quantities adds another layer of meaning beyond simply showing locations. One of the most important points this chapter made was explaining the difference between mapping raw totals versus using ratios or densities. In the beginning, mapping totals may seem straightforward; though, the chapter explained how this can be misleading. This scenario is especially common when areas vary in size. Larger areas can appear more important simply because they contain more, not because they are more concentrated. Given this context, it made me realize just how easily patterns can be exaggerated or minimized depending on how data is presented. Moving along the reading, I found the discussion on classification particularly interesting. The fact that the same data can look completely different depending on how classes are created made me think about how much influence the mapper has over interpretation (once again). Choosing natural breaks, equal intervals, or quantiles is not just a technical decision. This decision is interpretive and made from that of a human individual. Once more, these decisions reinforce the idea that GIS analysis involves judgment, not just calculation. Another aspect that stood out to me was how outliers can distort a map if they are not handled carefully. One unusually high or low value can change how all other data appears, which again highlights the importance of understanding the data before mapping it. Reading through this chapter made me more aware that maps showing “the most and least” are powerful, yet also risky if created without careful thought. In other words, the users of GIS are responsible for creating maps with intention and meticulous work. It reinforced that GIS is not about producing visually appealing maps, but about presenting information in a way that is accurate and intentional.