I’m Abby. I am a sophomore, and I am majoring in geography and environmental studies. I hail from Granville, Ohio, which is about an hour straight east of Delaware, but on campus I live in the treehouse! For some fun facts, I love animals, and I will talk about my pets endlessly if given the opportunity, and I love to bake, so if you need bread recipes, you can come find me. I also help run Ohio Wesleyan’s chapter of the Food Recovery Network, so if you want to join, let me know 🙂

-

The Schuurman article was interesting. I had no idea that the basics of GIS were such a hot debate. I knew from prior classes the application of GIS software has its controversies, but I didn’t realize that professionals still debate whether or not it is simply a way to visualize data or if it’s actually more than this. Furthermore, I also didn’t know that GISystems and GIScience were separate areas. While my knowledge of GIS is limited, I assumed that when geographers used GIS software, they were analyzing the data as well. It’s interesting that systems only focuses on the technical aspects of mapping.

The article is also interesting because it shows just how prevalent GIS is in every field now. Schuurman mentioned disease tracking and predicting, traffic problems, farming techniques, and public resources, all of which are remarkably different fields.

In my own research, I focused on the impact that GIS could have on natural disaster response. With the population increasing, an increasing urban density, and an increase in climate-changed caused storms, it is more important than ever to have precautionary efforts to mitigate these disasters. One such plan is run by civil engineers in Chittagong, Bangladesh, in which they mapped out locations of hospitals and other shelters in the city and implemented them into a map in order to help citizens find the nearest help/safety during earthquakes and floods.

http://103.99.128.19:8080/xmlui/bitstream/handle/123456789/252/A%20GIS-BASED%20ANALYSIS%20ON%20%e2%80%9cEMERGENCY%20DISASTER%20RESPONSE%e2%80%9d.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

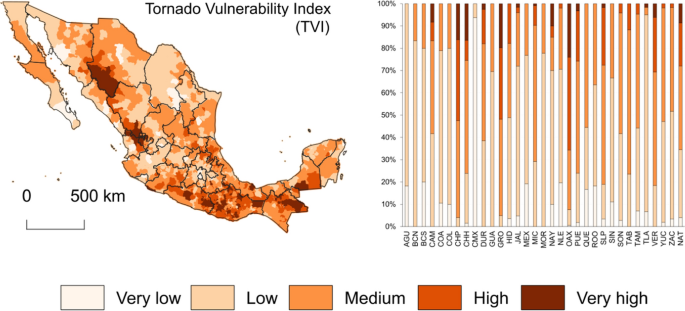

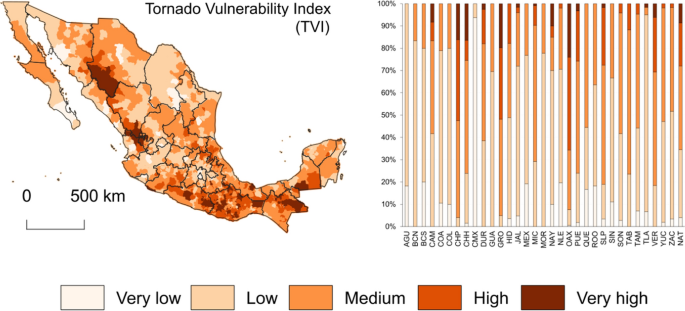

Another article I found is about tornado risk in Mexico. It was stated that tornadoes are a relatively common phenomenon in Mexico, yet this danger was not studied or really reported. In the article, scientists gathered information on the locations of inclement weather and compared it to social aspects of the same areas, such as structural characteristics, healthcare of the area, and age and mobility. Together, scientists used these comparisons to make a hazard index for the territories of Mexico. In this case, GIS was used to better understand the impact that tornadoes could have on different areas of Mexico.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11069-022-05438-0