Chapter 4:

This chapter talked about file geodatabases (FGDBs), which allow a large storage capacity and better performance in ArcGIS Pro. Before I read this chapter, I hadn’t fully understood the importance of FDGBs. Coming from a Biology background (before I changed my major to Computer Science), I initially thought of spatial data like large Excel datasets. Here spatial databases have geographic features, which makes them more complex than a simple table. Some cool things that I learned were that FGDBs allow fast queries and spatial relationships. This reminds me of databases in bioinformatics. In addition, I learned that FGDBs store multiple layers efficiently. Before, I thought shapefiles were enough. I now understand how limited FGDBs can be. They allow better organization, which makes them much needed for GIS. If I see a .gdb folder I now know that it means that it holds many classes, raster datasets, and tables. This chapter provided us with hands-on tutorials, showing us how to create geodatabases and how to import shapefiles. One of the tutorials showed us how to collect spatial data, like when it summarized crime incidents by neighborhood. As a Data Analytics major, I found it interesting how similar GIS queries are to data analysis tasks that I have done in Excel. This tool seemed more powerful, as you can filter data based on more stuff. Python is very valuable for ArcGIS and I would love to explore its use more. Some questions that were raised was if FGDBs have limits for large environmental datasets. Another question that I had was how can Python automate file geodatabase tasks in ArcGIS.

Chapter 5:

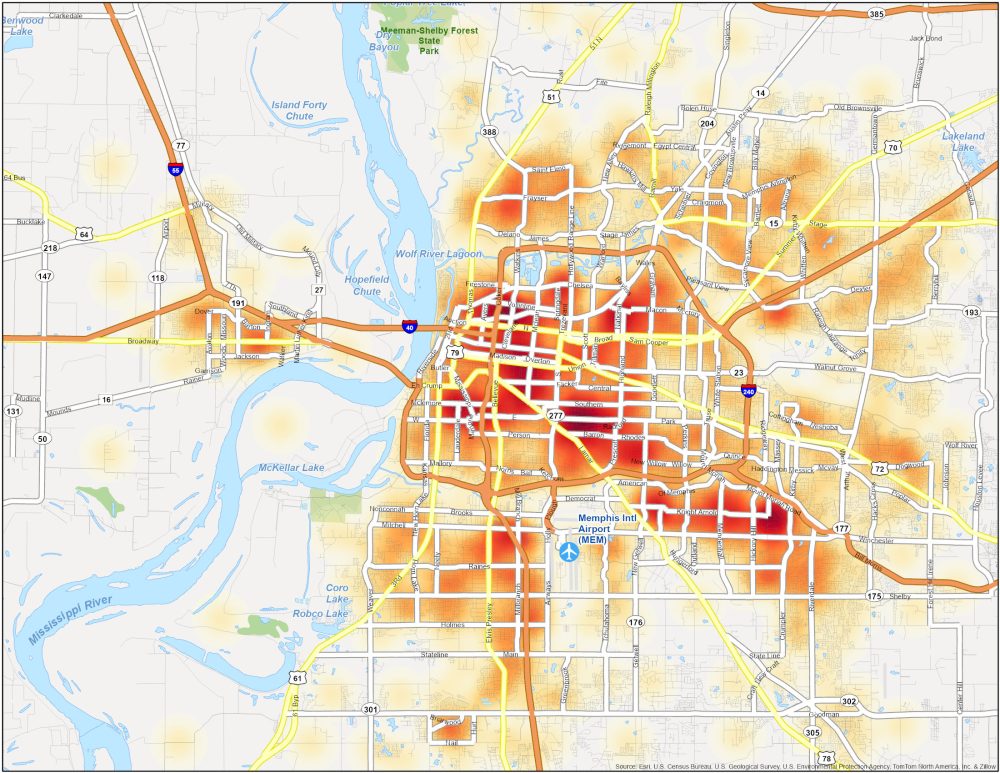

Before starting to learn GIS, I never thought about how maps can reveal hidden patterns. After reading this chapter I now get their importance and how powerful tools they are. This chapter talks about mapping an area. This is necessary as we can understand what is going on inside the mapped area. For example, where the highest crimes happen in a city, or which hospitals are within 5 miles of schools, etc. Instead of looking at raw data tables– which can be overwhelming most of the time- GIS successfully condenses and summarizes this data. I was familiar with latitude and longitude, but I had now idea about map projections and coordinate systems. I feel like I am learning a new language when I try to understand spatial data. I understood how easily things can go wrong if I don’t choose the right projection. I finally understood why some maps deform distances. Another interesting thing I learned was vector and raster data. I related raster data to a microscope image, as there are grids and pixels that have different intensities. From the tutorial, I saw that if I choose the wrong coordinate system the datasets will be completely misaligned, and that would ruin the analysis. As someone who hated high school geometry, I never thought that I would enjoy working with coordinate systems. The real-world applications made me appreciate GIS even more, as it showed me how important it can be for making decisions. I also learned that spatial data interoperability is how different data get to work together. Some questions I have are how does datum transformation affect GIS precision?

Chapter 6:

This chapter showed us that knowing what is near you is important for making decisions. Whether it’s finding the closest hospital or analyzing wildfire risks. GIS plays a fundamental role in spatial decision-making. I really liked how practical this chapter was. Geoprocessing tools allow you to repeat and automate GIS workflows without having to click through the menu. Some key takeaways from this chapter were the dissolving features, like merging school districts into larger administrative regions, clipping data, and merging datasets. The last one is essential when we have to deal with large environmental datasets. Lastly, spatial intersections, which for me was mind blowing. I liked how you can overlay two datasets and extract the affected area. What really stood out to me was geoprocessing. It is used by emergency services to assign fire stations to fire zones while making sure that the response times are the desired ones. In addition, straight-line distances are the shortest way possible between two locations. It can be simple, but can also be considered unrealistic because there are a lot of factors that should be taken into consideration, like how people are actually driving, sidewalks, crosswalks, etc. GIS isn’t just about mapping, it is about solving real-world problems. A question that I had was how geoprocessing scales with large data sets, like would it slow down? Another one was how GIS combines road issues and other things that must be taken into account in order to calculate and analyze locations more accurately. This chapter made me think about how much GIS impacts our everyday life without even knowing it. From finding what is the fastest way to go somewhere, to emergency responses. A final thought that I had when finishing this chapter reading was that I felt more confident about ArcGIS Pro. In the beginning, I struggled with what GIS is and what is its use, but now I am getting it