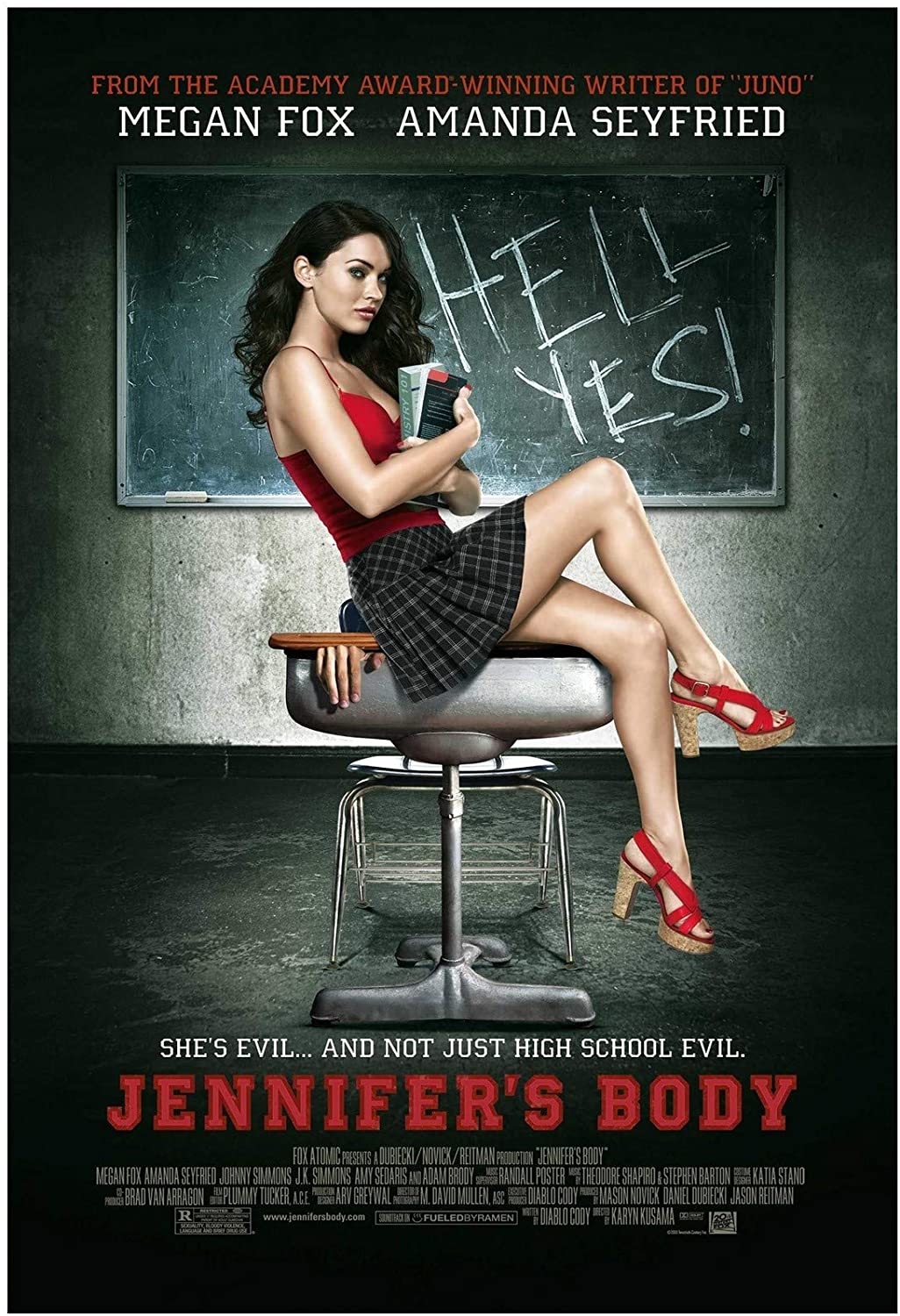

Every year as we enter deep into October and everything around slowly begins to merge into some form of “spooky,” I always find myself drawn back to my favorite horror films, whether because they’re scary or for entirely different reasons. Jennifer’s Body, a 2009 horror comedy written by Diablo Cody (Juno) and starring Megan Fox and Amanda Seyfried, is not only one of my favorite horror movies, but one of my favorite movies in general. I loved it the first time I watched it—and was thoroughly confused why not many people seemed to be loving it too—and continue to fall deeper in love with it and its many layers the more times I watch it, the more I learn about the horror genre in general, and the more I learn about the people behind making it. Over the last few years, Jennifer’s Body has slowly shifted under public perception from a movie once deemed trashy to a perfectly-aged cult classic of feminist horror. The film’s more recent reputation is deserved but many years late—the clever intentions and crucial message were always there, but in 2009 neither the industry not the public were too interested in the cinematic achievements a women-made movie about a teenage girl who eats boys.

The movie tells the story of Jennifer, a popular cheerleader who every other boy wants, and Needy, her shy and insecure best friend who admires her desperately. One night, Jennifer takes Needy to see a band, the two completely unaware that they are looking to sacrifice a virgin in a ritual in exchange for fame on that very night. Jennifer is the chosen one, but there’s a tiny issue: she isn’t a virgin. In the aftermath of the attempt, Jennifer transforms into a creature who still holds her alluring looks but which is no longer human—a demonic being who needs to feed on boys for energy. She is hungry, and a worried Needy finds herself desperately wanting to save her best friend from what she is becoming.

Jennifer’s Body is a very, very intentional play on the usual female revenge narrative: a woman suffers some sort of abuse (usually sexual) and then rises from the ashes to kill every man. It’s a tale told a million times before—Kill Bill, Spit on Your Grave, Hard Candy—and to be told a million times to come. There is a reason why female anger regarding trauma is such a recurring topic, but ultimately many of the movies that take on this plot structure end up coming off, especially to women, as utterly unrealistic. The anger itself is certainly relatable, but the narrative in which a woman triumphs over her abusers in shiny and violent fashion doesn’t tend to quite match up with reality. Last year, the movie Promising Young Woman came out, offering a much more honest take on what the revenge narrative really is—and, in a way, Jennifer’s Body was doing the same over a decade ago. The film embraces the extravagant nature of the revenge trope and commits to it unabashedly—Jennifer’s murdering of boys is so utterly satirical and exorbitant we almost forget it’s revenge. We see an emotionally disconnected Jennifer who is essentially a monster, but when we are forced out of the fun, unapologetic gore, we see a version of her which is slowly decaying since her trauma. Though her decaying is presented to us as a metaphor of hunger, as we watch we are forced to face the disconnect between the two sides of Jennifer: one is an entertaining character in an entertaining movie, another is a reflection of all the women who are fighting hard to recover from trauma, anything but fiction.

As well as playing with the abuse revenge trope, Jennifer’s Body embraces its status as a horror comedy and works within that framework to sharply deconstruct tropes of horror, too—and in doing so, it exposes how rooted in misogyny many of them are. The character of Jennifer herself is a rendition of a well-used horror character archetype: “The First Girl.” In essence, the archetype is exactly that: the first girl to be killed. Her most defining characteristic is the fact that she is promiscuous and open about how much she enjoys sex. In most slashers, Jennifer would be gone by the twenty-minute mark. In Jennifer’s Body, we spend the entire remaining screen time following the aftermath of the abuse that should have killed her, as she takes back the narrative and becomes the danger herself. Not only that, but the very thing that saves Jennifer from actually dying is the fact that she isn’t a virgin—if she had been, the sacrifice would have worked. The thing that allows her to kill so many men is also her sensuality: men can’t help but follow her into deserted areas, the perfect setting for literally biting into their necks. The unapologetic enjoyment of sex, which is so often the weakness of so many female characters in horror films, is in Jennifer’s Body the titular character’s biggest strength, the exact thing which transforms her into an unprecedently dangerous and powerful creature.

Her best friend Needy, on the other hand, represents a horror archetype at the opposite end of the spectrum: “The Final Girl.” This is the character that survives, the girl who wins over whatever great evil threatens her. Most times, the final girl is also a virgin—a clear reflection of the persisting belief (both in the media and outside of it) that women are not worth dignity if they’re not sexually pure. Needy is an embodiment of the Final Girl: innocent, virginal, upright, the exact contrast of her best friend. However, like Jennifer, Needy emerges beyond the archetype she represents. Behind her innocent admiration of Jennifer, there are many repressed feelings of attraction Needy seems to refuse to accept. Between the lines of the script, is the fact that Needy—the film’s rendition of an inherently heroic character—sees herself in all the men that desperately want Jennifer–the simultaneous villains and victims. The key difference is that these men see nothing but Jennifer’s body, failing to realize it is much more than a body (the disconnect between what men look at when they see Jennifer’s body and what her body actually does to them is the ironic origin of the movie’s name.) Needy, on the other hand, sees Jennifer for all of what she is, the good and the bad—which is perhaps exactly why she is the final girl. Additionally, there’s a very important event in the movie that further deconstructs the misogynistic foundation of the final girl trope: Needy loses her virginity. The movie still plays with the trope and the possibilities it offers, but only allows itself to do so when it’s freed from the sexist implications that come along. In the cases of both Jennifer and Needy, archetypes are a framework under which real women come alive in the moment their existence and value are separated from their sexuality.

Another way in which Jennifer’s Body subverts the misogyny of these tropes is through the underlying relationship at the center of it. Jennifer and Needy have been best friends for years, but under the surface of their close friendship are sexual and romantic affections, complicated by the jealousy and protection they often feel towards each other. Needy’s boyfriend Chip is portrayed as a dull contrast to her attractive and perpetually interesting best friend, and all the men Jennifer eats are as easy to kill as it is for a hot girl to lure them into quiet areas. Intentionally, there isn’t much dimension to a lot of the male characters, which contrasts the complex and layered relationship Needy and Jennifer have with each other. This even further removes their value as characters from their connections to men, driving home the point that, though Jennifer’s Body is a horror movie, it won’t give into the sexist implications many of the genre’s usual tropes carry.

The retelling of the revenge trope through the gory lens of a feminist horror comedy was exactly writer Diablo Cody’s intention—her target audience in mind was teenage girls and young women, as she knew they would see themselves in the allegory of Jennifer’s story. The production company had something else in mind: Megan Fox was the one playing the protagonist, and the assumption was that, with a popular sex symbol at the forefront, the movie had to be marketed towards men. Due to this equivocal marketing strategy, the young women the movie was written for didn’t go watch it, and the men who were expecting to see a half-naked Fox filmed in suggestive camera movements left disappointed and disconnected from a narrative that, on the surface, painted men like them as nothing but hot-girl food. Along with camera movements that refused to sexualize Fox the way she had been captured through so much of her career, (an obvious result of the fact that the movie’s director is a woman) the plot didn’t land with either of the target audiences.

Naturally, the film was a box-office disaster. It certainly didn’t help that by then Fox was perceived as a mere sex symbol—talent was an afterthought when discussing her presence in the industry. This is a reputation that still precedes the actress, and it is the reason why, despite her years of career showing her ability to excel in a range of characters and genres, Fox still doesn’t get many parts. During the making of the movie, she was aware of how her reputation was implicated in its message, but still felt passionate about the project; after the release and initial fail, she continued to recognize the movie as her favorite she’s been in, and to this day is proud to claim this. Fox saw her own life reflected in Jennifer’s journey: at that point, she was excoriated by the men around her in the business, left to deal alone with the consequences of the ways they treated her. Like the women Jennifer’s Body was written for, the star of the movie herself saw in that script the untold anecdote of what she had been through. In many ways, the reasons why the film failed are the same that fueled the making of it in the first place: women having their voices stolen from them and being deemed as nothing but sexual objects.

Throughout the years, though, as our society has become a little more ready to listen to women (key word: little), the intention that was always behind Jennifer’s Body started to finally come through. The appeal of clever feminist social commentary paired with some cannibalistic gore started began to get the recognition it deserved, and slowly the movie turned into a cult classic. Though it took a decade too much, Jennifer’s Body is finally getting the recognition it deserves for its crazy, beyond-its-time concept, and most of all for the talent of all the women behind it—Diablo Cody, Karyn Kusama, Megan Fox, Amanda Seyfried, to name a few. The horror cult classic status is much, much more than deserved—and I’m excited to keep watching it on Halloween knowing the message behind Jennifer’s Body is each year being heard louder and louder.