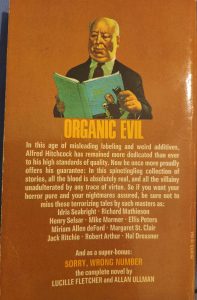

“Organic Evil.” These are two words that Alfred Hitchcock uses to describe the tone of the stories that make up the collection titled Alfred Hitchcock Presents: More Stories NOT for the Nervous. Hitchcock and author Robert Arthur worked together to gather many thriller short stories that they thought were amazing and put them all together in this collection.

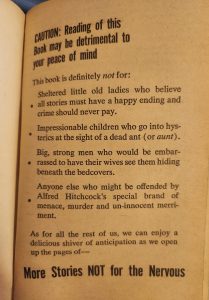

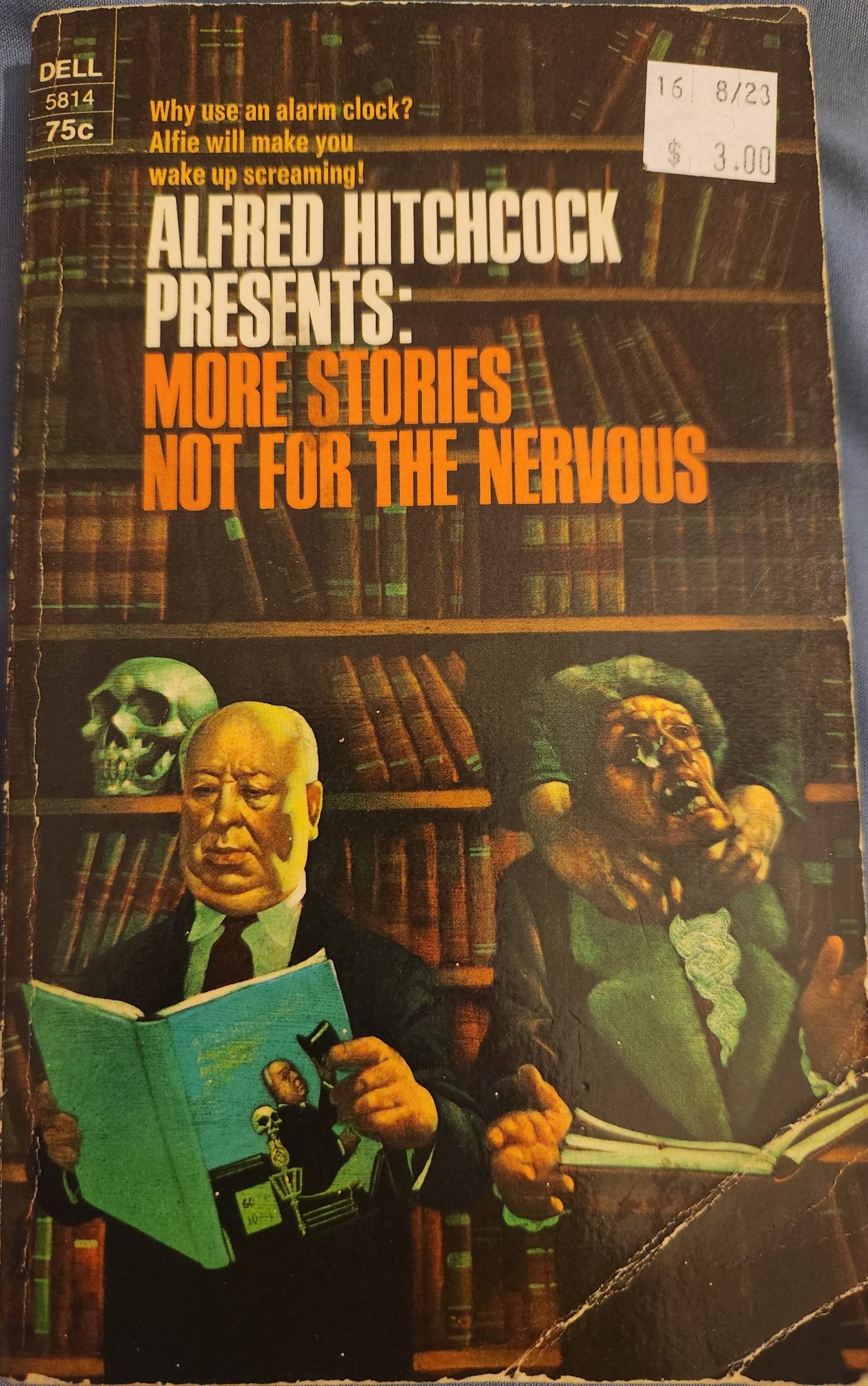

Hitchcock wants every aspect of this book to make you feel uneasy, frightened, thrilled, cautious, and possibly a little amused. This is evident even from the cover art which features a painted illustration of a skull resting on a bookshelf behind Hitchcock’s unperturbed body, as he seems to be reading another collection of his scary stories; to the right of Hitchcock’s body is an elderly person screaming as two hands protruding from the bookshelf behind them are grasping the person’s neck. Hitchcock has some more fun through fake warnings on the first page: “CAUTION: Reading of this Book may be detrimental to your peace of mind.” The structure of many of these stories are perfect examples of what makes a great scary story.

In anticipation of Halloween, I want to discuss two short stories from this collection that shocked and moved me the most, and that I hope will do the same for you. “View From the Terrace” (1960) written by Mike Marmer jumps right into the falling death of a man named George Farnham. We follow the events through his widow’s eyes, and are quickly told it was a murder, but it is unclear for most of the story who the murderer is, creating a surprise ending. Similarly surprising is “Call For Help” (1964) written by collection co-editor Robert Arthur, which follows two elderly women who take desperate measures to escape the family who they believe want them dead.

Some common elements between these stories that I found to be key to great thriller storytelling include the subversion of the readers’ expectations of the protagonists’ motivations and moral character; ambiguity as a tool that heightens tension and drives suspense, so that critical parts of the narrative are unclear to the reader until the end; the desire for vengeance and how it ends up creating more calamity for the protagonists who believe their actions against others are morally justified; and finally, a sense of helplessness that motivates the protagonists to perform outrageous and desperate acts in order to free themselves from their pain or suffering as they feel there is no other way out.

Mike Marmer’s “View From the Terrace” utilizes all these narrative devices effectively. The story starts off with beautiful imagery of the Jamaican sun in the evening, and then suddenly juxtaposes this with a man falling from a hotel balcony to his death, his “arms flailing wildly, descending scream trailing behind.” This man was George Farnham, who was on vacation in Jamaica with his wife, now widow, Priscilla Farnham. With this sharp contrast in imagery, we already see an example of subversion at play in this story, which alludes to a sinister occurrence under the guise of a happy family on vacation. For much of the story, there is ambiguity over who killed George and why. The reader most likely assumes right away that Priscilla killed her husband; however, we learn later that the truth is more complicated.

What made this story so surprising was that the author made Priscilla seem cold, unaffectionate, and vengeful towards her husband, and absolutely capable of his murder. One of the earliest descriptions of the late George Farnham is through Priscilla’s eyes, who she says “appear[s] strangely like an isolated piece of a jigsaw puzzle.” This immediately creates a disconnection and a lack of empathy from the reader towards George. Priscilla, his own wife, does not seem very distressed about his demise, so why should we? However, this description also makes one ask, what kind of wife compares the sight of their recently deceased husband to a stray puzzle piece?! We realize right then that Priscilla does not think highly of her husband.

In addition, when the police arrive to interview Priscilla she is portrayed as wearing a “mask of grief-stricken widowhood.” This is more narrative misdirection to convince the reader to believe that Priscilla killed George because she no longer cares about him. Moreover, Priscilla quickly establishes that George’s death was undoubtedly “Murder!” However, the tension continues unabated as it is not explicitly stated who killed George and why for most of the story. The reader is tricked by the mechanisms of this story into believing that Priscilla is the killer, but that’s not much of an exciting thriller if the killer and their motives are revealed right away, so that is why we keep reading. We want a definitive answer and to be told boldly who the murderer is.

We never get a clear answer but it is alluded to in the end that the true culprits are Priscilla’s children, Mark and Amy. With all of Priscilla’s worrying and strategy before and during the police interview, we think that she is scrambling to defend herself, but she is actually motivated by the love she carries for her children to do everything she can to protect them from the repercussions of murder, even potentially taking the fall for the murder herself.

A slightly ambiguous motif that drives this story is “the Game” that Priscilla plays with her children, in which they have to guess what surprises they have prepared for each other. The game becomes important at the end of the story. That is when the most significant yet very subtle utilization of subversion occurs. After the police interview concludes, “[t]he children, their beautiful faces beaming with their surprise, had pulled her out to the terrace, pointed over the railing and chanted, “Guess what we did for you today!” This line is powerfully shocking as it suggests that her innocent-seeming children killed their own father. The reader’s perception of both Priscilla and her kids changes from likely seeing Priscilla as a cold-blooded husband-murderer or a woman who acted in a moment of exhausted rage, to a desperate mother protecting her children from their own mistakes. The reader further may fear the children now as it is extremely disturbing to kill your own father as part of a “game.”

This murder is many things. It is a twisted act of “fun” for the kids, it is a gesture to make their mother happy again and free her from her troubles, but most of all, the murder is an act of vengeance. The kids were pained to witness their parents arguing, and in being closer to their mother, they despised how their father was hurting her, and confining her to a sense of helplessness. Priscilla’s kids removed her main source of pain and unhappiness, yet they did not seem to register the wrongness and seriousness of their actions. Evidence of this failure of Amy and Mark to register their act as being a horrible crime is when they are discussing the rules of “the Game” to the Detective, Sergeant Waring. They offer to tell the Detective what they recently did for their mother (i.e., push their father off the hotel balcony). Their false innocence is preserved as Waring suggests that they should keep their surprise a secret. At this moment in the story the reader has not been told yet that the kids are the murderers, but upon reading the story again your stomach drops when you realize how close the kids came to openly confessing to murder. It is utterly wild how they are not aware of the malice of their actions, and leaves the reader with chills.

Our second story, Robert Arthur’s “Call For Help,” is set in a New York autumn and follows two elderly sisters, Martha and Louise Halsey. On the first page of this story Martha is already trying to convince Louise that their niece, Ellen, and her husband, Roger, are trying to kill them for their money. Most of the story is Martha building up her case, finding “evidence” of Roger and Ellen seemingly planning and attempting to end her and her sister’s lives, until Martha sets fire to their house with Roger and Ellen locked in the basement. Eventually, the sisters’ previous fears are turned on their head after a sobering conversation with their trusted friend and adviser, Judge Beck.

Once again, the most noticeable use of subversion of the readers’ expectations happens at the end of the story. Martha tricks Ellen and Roger into going into the basement to look for her cat Toby only to lock the door behind them, and set fire to the house. Not even Louise expected her sister to do that as Martha kept parts of “her plan” secret from her sister. At this moment, we see the extreme measures that Martha is willing to take in order to gain autonomy over her life again. No longer do we think that Martha is a harmless old lady. We knew she was clever and determined but did not know if or how she would get rid of Roger and Ellen until this horrible event unravels.

As in “View from the Terrace,” the murderer’s motivation is critical to the story’s thrilling effect. Martha believes that the “only way” that she and Louise could get help is to burn the house down to get rid of Roger, Ellen, and the house they feel trapped in. This act of violence is also an act of vengeance. Martha wants revenge for being pushed out of her home by Roger and Ellen, for the poison death of one of her two cats, and for the lack of freedom and luxuries she and Louise have endured recently while living with Roger and Ellen.

Additionally, the author conveys Martha’s selfish mindset and lack of guilt by juxtaposing the house fire that she started with the comfy fireplace in Judge Beck’s office. At the end of the story Martha and Louise meet with Judge Beck in hopes that they will discuss returning to their father’s home. The author utilizes juxtaposition in his narrative description of these two moments writing: “But the rest of the house was engulfed in flame then, and there was nothing the fire company could do.” After the fire, the sisters are sitting in Judge Beck’s office to discuss the next steps of their lives without Roger and Ellen’s oversight: “The fireplace in Judge Beck’s living room crackled cheerily.” Many times throughout the story the sisters will reminisce about the fireplace in their father’s home. This odd juxtaposition, particularly after Martha burned down the house, lessens the empathy and guilt that the sisters may have felt, as this murder is being compared to a source of comfort and safety to the sisters. This simply makes Martha seem satisfied and glad that she killed Roger and Ellen, and that she can be free to live how she wants again.

I will admit, however, that there are instances of ambiguity around the motivations for some of Roger and Ellen’s actions, which bolster Martha and Louise’s accusations: Ellen and Roger put an ad in the paper for Martha and Louise’s house without their aunts’ permission. There is the matter of Martha’s missing cat Toby, who the sisters believe has been poisoned. So when Louise suddenly gets sick, she suspects that she has been poisoned, too, and is very concerned about how she can overcome this apparent predicament, let alone even keep living long enough to get help. But when Louise felt sick Ellen was hesitant to call the doctor, and there are frequent “exchanged looks” or “glances” between Roger and Ellen. Finally, Martha and Louise try desperately to contact Judge Beck for help getting their old house back, and to inform him of Roger and Ellen’s apparent “intent to kill them”; however, Judge Beck is nowhere to be found. The sisters are told at one moment by Roger and Ellen that Judge Beck is in Boston, but then later a Doctor Roberts informs the sisters that Judge Beck is not in Boston, he is just sick. The ambiguity over some of Roger and Ellen’s actions and the whereabouts of Toby and Judge Beck, reinforces for the reader the suspicion and confusion that Martha and Louise are experiencing. All of these moments make Roger and Ellen seem suspicious, so we initially lean towards Martha’s assertions that they are trying to kill her and her sister until Martha takes matters into her own hands.

Throughout the story Martha seems to have an insatiable thirst for control and vengeance which overpowers Louise’s timidity and initial doubt surrounding the possibility that Ellen and Roger could have been planning their deaths. The women repeatedly go over the “evidence” for their claims, mainly being that one of their cats that went missing was found poisoned, Louise has been suffering sudden spells of sickness, and as a pharmacist Roger has easy access to drugs and poisons. Martha drills these observations into Louise’s head until she believes them too. The reader is also inclined to believe these claims right away because we are told from the beginning that they must be happening, they sound rational, and they foster the image of two helpless old ladies who would do no harm.

The importance of surprise for subverting readers’ expectations is at its strongest at the story’s ending, when Judge Beck unknowingly pulls the rug out from under many of Martha and Louise’s assumptions, and therefore the reader’s too. First, Judge Beck surprises the ladies with their missing cat Toby who was found wandering by the house after the fire. Second, he explains to them that his visit to Boston was not for another client but over their own affairs. Third, the Judge reveals that he was in Boston but had to return home early because he became ill. And the last blow is when he tells them that their father’s house, which they hoped to return to, has no value and is “uninhabitable.” The author bombards the sisters and us with this mountain of indisputable truth. Martha and Louise were wrong about Roger and Ellen trying to kill them. Their niece and her husband’s lack of transparency with them sadly led to suspicion, conflict, and ultimately, to their deaths. It is also unfortunate how Martha ended up punishing herself and her sister, as they now must resort to living the rest of their lives in a facility for the elderly known for its poor living conditions called “The Haven Home.” The last lines of the story is Louise whispering this name with dread while “Martha’s voice would not come at all.” I found these lines to be powerful as clearly both women realize that they were wrong. Now they truly are in a state of great helplessness as they can barely speak after knowing that they subjected themselves to a miserable life at the Haven Home, all because they thought their actions were justified when they really were not.

It’s safe to say that Hitchcock knows how to pick thriller stories that can also be amazingly insightful. “A View From the Terrace” is not just a murder mystery, but revolves around a mother’s love for her children, and the ethical dilemma of striving to maintain the innocence of children that do not recognize that murder is wrong. Likewise, “A Call For Help” is not about the exploitation of two old ladies, but rather the consequences of acting from unfounded assumptions, and how easily desperation can triumph over reason. Hitchcock shows us that there can be more to scary stories than screams and gore. They can make us ask ourselves how we live our lives. They might even make us look at our neighbors, friends, and family differently. If you look around enough you don’t need a ghost or a crazy man with a knife to scare you–there are plenty of unsettling things in our daily lives to make you want to look over your shoulder sometimes.

Wow – this is such an impressive, beautifully written analysis! You don’t just summarize the stories; you dissect them with such precision and empathy. I love how you tied Hitchcock’s concept of “organic evil” to the moral ambiguity and desperation that drive these characters. Your writing has such confidence, and your interpretations are both sharp and deeply human. It’s clear you have both a literary and psychological grasp of these stories, which makes your analysis feel both academic and emotionally intelligent. I was totally drawn in from the first paragraph 😀