When I first sought to play the game Death Stranding, I did so from a place of curiosity. It had been three years since the release of the game by legendary video game creator Hideo Kojima, which had received mixed reviews and sparked heated online discourse. In the past, Kojima was celebrated for his continued championing of the Metal Gear series since its inception in 1987 with the original Metal Gear to its contemporary titles like Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain. Kojima was so prolific in the industry for his creative vision that he was able to convince Guillermo del Toro, Academy Award-winning director, to help with the creation of a reboot to the critically acclaimed Silent Hill series known as Silent Hills, starring Norman Reedus. Unfortunately, due to circumstances related to Konami hindering his creative visions for games, Kojima made a decision to leave the company and strike out on his own. This left Kojima with nothing but ambition and his notorious reputation to create a game studio. Along with other employees from Konami and other new creative talent he set out with the sole goal of fulfilling his creative vision. This was the beginning of the studio known as Kojima Productions, the title that would see Kojima’s return to the gaming industry.

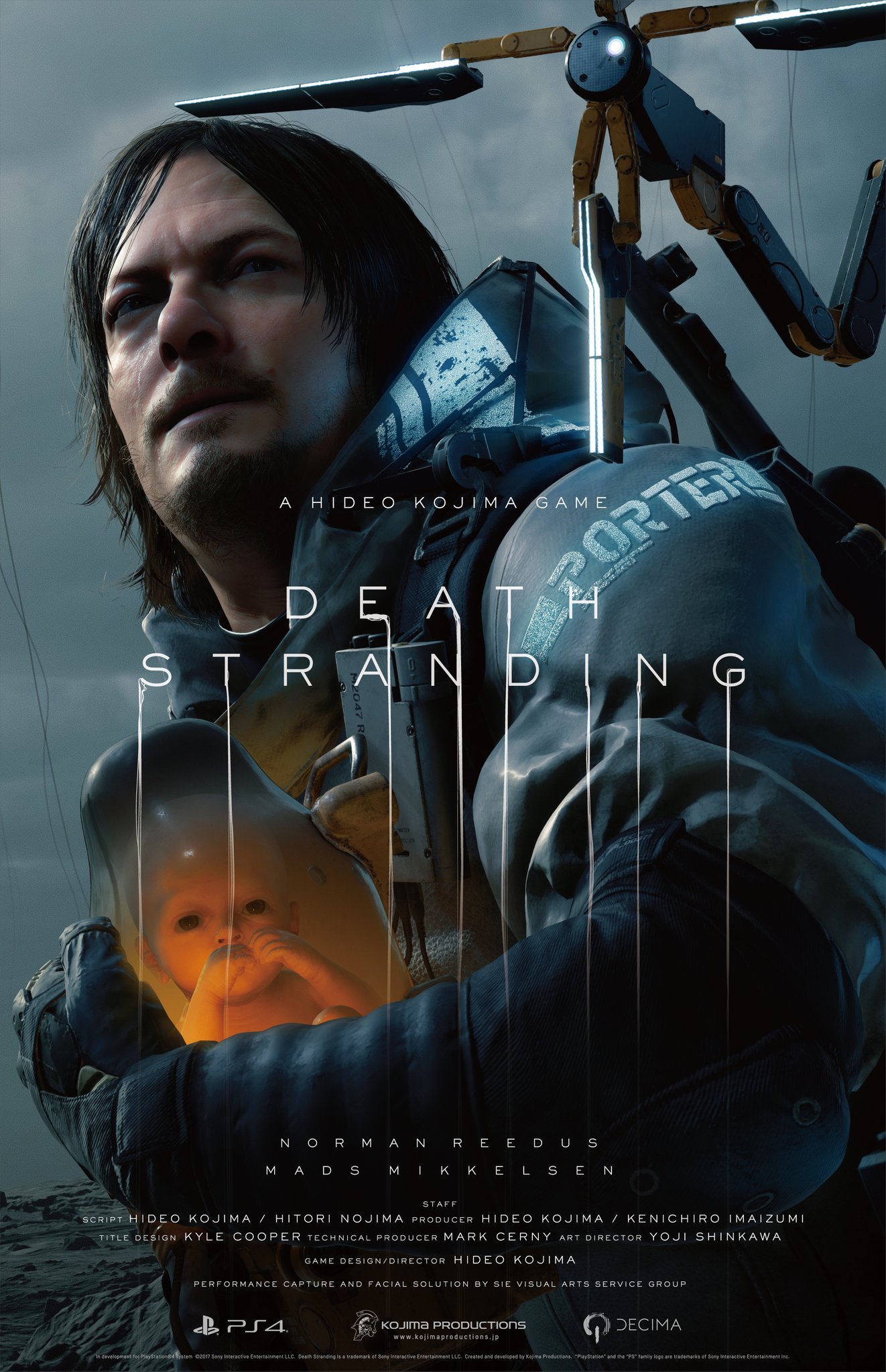

Kojima is often put front and center when discussing Death Stranding, as his name and vision were what people in the gaming industry had come to love and trust. Kojima is the project head, the face of the campaign, and appears in multiple trailers for the game, some of which are edited by Kojima himself, marketing the game as “A Hideo Kojima Game.” The trailers for Death Stranding were vague, dreamlike, and rarely gave a whole picture, let alone any image of what the game really was. What was the game actually like to play? Why did so many people find it controversial? With the long-awaited sequel, Death Stranding 2: On the Beach, arriving this year, what will Kojima be seeking to task his players with next?

Many have their own words to describe Death Stranding, but the one I often stumbled across was “walking simulator.” In Death Stranding, the gameplay is often a means to continue the progress of the game’s story. As Sam Porter Bridges (Norman Reedus), you are a courier living in isolation in a post-apocalyptic America in the wake of an event known as the Death Stranding, where spirits of humans and other dead creatures known as Beached Things (BTs) are stranded in the land of the living and seek to “connect” with humans. Your goal is to make deliveries to and from cities, known as Knots, as well as some small outposts and way-stations, to reunite a fractured America under the banner of the United Cities of America (UCA) via a resource known as the Chiral Network. All the while delivering these packages, you will be accosted by all manner of obstacles. Cargo thieves, known as MULEs, will attempt to steal these important packages while acid-like rain known as Timefall will deteriorate your cargo. Rough terrain, as well as rapid rivers and streams, will threaten to make you fall, causing you to lose your cargo. The largest threat of all, however, is the BTs, which cannot be stopped by any conventional means or weapons and must be avoided at all costs, lest you be dragged hundreds of feet from your cargo and be met face-to-face with a creature of eldritch horror.

To aid you in your mission, your most important and reliable tools are your Bridge Baby (BB), a half-dead infant, stuck in a simulated womb housed on your chest and the Odradek Navigation System (ONS), a shoulder mounted device which can be used to scan the surrounding environment. Paired together, these tools help you navigate the dilapidated America by setting waypoints and destinations to where you need to go. BB will allow you to see the normally invisible BTs. This, paired with tools made to construct bridges and other structures, unlock-able weapons and vehicles, and the occasional boss battle, should equal at least a pretty good experience. However, this culminates in an experience that, in my opinion, is more preoccupied with telling an amazing, convoluted story and meta-narrative, with a few flaws that make it a great game for some, yet runs a certain mileage with others, depending on how much deliberate annoyance they are able to endure.

To me, there is no denying the strength of Death Stranding’s overarching narrative as well as that narrative’s implementation into the gameplay. The central theme of Death Stranding is connection—overcoming the various obstacles thrown at oneself to keep them separate from others. The protagonist, Sam, at the beginning of the game, starts as separate from those whom he cares about because of the discovery of his ability to return from the world of the dead (respawn) whenever he is killed. The online functionality of the game allows you to connect with and share materials and structures with players in their own worlds, which can help you overcome a literal chasm separating you from your destination, encouraging you to connect and not go it alone. You can assist other players with deliveries, rebuild their structures, and create safe houses. The more Knots and outposts you connect and the deeper connections you forge in those areas, the more rewards you receive for your efforts such as new tools, vehicles, or weapons that make the experience more manageable. All of these mechanics are optional, and you can traverse the world of Death Stranding with nothing more than a baby and a dreamcatcher. I can understand why some people would be frustrated with this game because if you choose this path of solitude, much like the protagonist Sam, the journey will become far more difficult.

The message Hideo Kojima is trying to reinforce through the narrative is that if we stay separated like Kojima was at the start of his journey with Death Strandings development and refuse to put our petty differences and grudges aside and come together, we will never make progress, and the experience will be long, arduous, and tedious. However, if like Kojima and his fellow developers we come together and lighten the load on someone’s back, we can make the journey easier, and while there will inevitably always be suffering, at the very least, we aren’t suffering alone. Death Stranding is special to me and so many other people because I believe it speaks to that part of us that wants to help and connect with those around us. However, the sequel to Death Stranding, throughout its current string of marketing, poses a different question: “Should we have connected?”

In other words, what are the costs of the knots that tie us together? How has connecting the world of Death Stranding opened it to not just more safety and community but new potential threats? Community and a nation wide government might be reorganized under the UCA, but will this restored government oversight prove reassuring or disconcerting, and what methods will be used to enforce their laws? In the effort to establish a nationwide network will porters like Sam become more essential than ever, or will they become obsolete due to other avenues or delivery and communication. How will the UCA reach out to other countries outside the network? Will it be with diplomacy or will it be by force. Kojima and his team are hard at work to package the contents of the on the Beach and deliver it on schedule. Personally given all this potential and my experience from the first game I can’t wait till June 26th when I finally unpack the contents of this intriguing and mysterious package.