There are many authors committed to writing about black British communities in England. These are just a few of those authors that represent different immigrant and marginalized communities. These writers are writing across all different platforms including poetry, playwriting, song writing, and narrative writing. All these authors have their own unique perspective and experience that they bring to their work. Here are a few to check out.

Black and Asian British Playwrights

Roy Williams

Roy Williams was born in Fulham, London on January 5th, 1968. He is a West Indian Britain playwright with a focus on a West Indian background. He was the youngest of four siblings in a single-parent home, with his mother working as a nurse after his father moved to the US. He left school at the age of 18 to be able to work to help support his mother. His favorite job was working in a prop house and this is where his love for theatre began. When he turned 25, he earned a degree at Rose Bruford College. He produced his first full length play, The No Boys Cricket Club, in 1996, which premiered at Theatre Royal Stratford East. Since then has written twenty plays. Williams has done writing and producing in television, including adapting his own play Fallout. He also co wrote the script for the 2014 British film Fast Girls. His plays have won many awards. Including the South Bank Show Arts Council Decibel Award 2003 for his play Fallout. In 2001, his play Clubland won the Evening Standard Charles Wintour Award for Most Promising Playwright and Lift Off. He was the first recipient of the Alfred Fagan Award and winner of both the John Whiting Award in 1997 and the EMMA Award in 199 for his play Starstruck. In 2008, he was appointed Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) and now sits on the board of trustees for the Theatre Centre. William’s addresses problems of race, ethnicity, and the importance of cultural knowledge in many of his plays.

Bola Agbaje

Bola Agbaje was born in South London, England in 1981 to Nigerian parents. After earning her media communications degree and a brief acting career, she found passion in writing about the tribulations surrounding race relations. Agbaje is a popular English playwright whose most renowned work, Gone Too Far!, was made into a film in 2013. Her career as a playwright began in 2006 when she joined the Young Writers Program at London’s Royal Court Theatre. It was here that she created her first play, Gone Too Far! After graduating just a year later from the program, her play was performed at the Royal Court. This successful showing gave the play immediate attention from fans and critics alike. In 2008, Agbaje received the “Lawrence Olivier Award for Outstanding Achievement in an Affiliated Theatre” for Gone Too Far! It was this year that she was also nominated for the “Most Promising Playwright of the Year.” This work made such an impact in English theatres that it was made into a movie in 2013. Gone Too Far! was performed in an array of London theatres: the Young Vic Theatre, Soho, and the Hackney Empire. Although this play is one of her most successful works, she has plenty of worthy plays: Detaining Justice (2009), Off the Endz (2010), Belong (2012), and Take A Deep Breath and Breathe (2013). An exhaustive list of her plays can be found here.

Tanika Gupta

Tanika Gupta was born on December 1, 1963 in Chiswick, Hounslow, London, England. Her nationality is British with Bengali descent. She has not only written works for the stage but has written television scripts and radio plays as well. She completed her education at Oxford University with a degree in Modern History. Before she started writing plays she worked as a community worker as well as an Asian Women’s refuge for several years before she began writing full time.

Gupta started writing plays in 1995 and continues to write plays today. She started with her play “Voices on the Wind,” which was produced at the National Theatre Studio and has continued with at least one play per year through her most recent work Anita and Me, which was performed at the Birmingham Rep. She has won multiple awards in her career in theatre including John Whiting Award for The Waiting Room, Laurence Olivier Nomination for Outstanding Achievement in Affiliate Theatre for “Fragile Land “I” Hobson’s Choice.” She has also won the Asian Women of Achievement Award (Arts and Culture Category) in 2003, and she is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature (2016). In 2008 she also became a member of the Order of the British Empire.

She has also given back to the arts community through teaching her craft to others. She has taught writing courses at Royal Holloway College, University of London and at the Central School of Speech and Drama, while also offering seminars in Glasgow and at Oxford University, her alma mater.

In an interview with the Guardian, on February 14, 2011, she stated that she rejects the label of an Asian writer. She does not want her work to be labeled in a way that only reaches out to one specific audience or covers one issue; her plays are for everyone. Gupta notes the treatment of treatment of colored playwrights in her interview, “You don’t hear Tom Stoppard being referred to as a Czech writer or Harold Pinter as a Jewish writer.” They are read for the greatness of their plays not who they are written for.

She is married to David Archer who is an anti-poverty activist whom she met in college. Her play Sanctuary is based on their honeymoon location, a war-torn Srinagar in Kashmir in 1988.

debbie tucker green

debbie tucker green was born in London, and is of Jamaican descent . She asks that her name, as well as the titles of her work be written in lowercase letters. green began her work in the theater as a stage manager, a position she worked in for 10 years before a friend encouraged her to submit her work She Three for the Alfred Fagon award. This award is given to playwrights of African or Caribbean descent who reside within the U.K. green did not win the award but her play brought her work into the attention of the Royal Court Theater and thereby began her career shift into writing and production.

Her productions tend to be about the darker sides of normal situations, such as families and conflicts between locals and tourists (like in her work, trade). green’s works dirty butterfly, born bad, and stoning mary all focus on the hidden complexities of family relationships including topics of domestic violence, sexual abuse, and murder within the family. green works largely with language and uses intertwining and overlapping dialogue between her characters to create both tensions and understandings between them.

green has won multiple awards, including the Olivier Award for Most Promising Newcomer for her play bad born and a BAFTA award for her movie production of random. She has now worked as a screenwriter and director for movie productions for her works, second coming and random.

Black British poets and songwriters

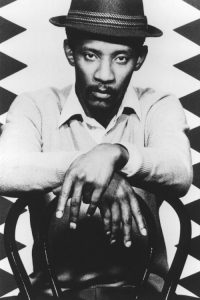

Linton Kwesi Johnson

“It is noh mistri/Wi mekkin histri/It is noh mistri/Wi winnin victri.”

The “father of dub poetry” and the first Black author to be featured in the Penguin Classics series, Linton Kwesi Johnson’s poetry tells blunt and shocking stories of police violence, racism experienced by Black youths from white supremacists, and outright violence that protesters want to throw back at the oppressors (British Council, “Linton Kwesi Johnson-Literature”).

Johnson was born in 1952 in British-colonized Chapelton, Jamaica. In 1963, he moved to London to live with his mother. He eventually went on to study Sociology at Goldsmiths College, University of London, where he graduated from in 1973. The university holds his old class papers in their archives. While at university, Johnson got an early start as a social activist, joining the Black Panthers in 1970 and starting a poetry workshop and movement within his chapter (Poetry Archive, “Linton Kwesi Johnson”). He also joined a group called Rasta Love, which featured both poets and percussionists. Johnson created the term “dub poetry” himself to describe poetry styles that mirrored how reggae DJs would blend verse and music together. But, he refrains from describing his own poetry as “dub poetry,” preferring to be a poet first and not a musician (British Council, “Linton Kwesi Johnson-Literature”).

A year after graduating from university, Johnson joined the Brixton-based collective Race Today, which published his first book of poems titled Voices of the Living and the Dead. His second book, Dread, Beat An’ Blood, was released as a book in 1975 and later as record with a reggae band in 1978. He went on to release several more albums like this on the Island record label before starting his own label called LKJ (British Council, “Linton Kwesi Johnson-Literature”).

In 1977, Johnson earned the C. Day Lewis fellowship at the London Borough of Lambeth and was their writer-in-residence. He also worked at the first British center for Black art and theatre, the Keskidee Centre, as the Library Resources and Education Officer. He won a silver Musgrave medal in 2005 from the Institute of Jamaica for his work in the poetry field (Poetry Archive, “Linton Kwesi Johnson”).

Johnson has lived in the historically Black neighborhood of Brixton almost all of his life in England, and much of his work focuses on the injustices that people of color, poor people, and the working class experienced in Brixton. His work particularly features stories he witnessed firsthand while growing up of exploitation in the workforce and the “sus” (suspicion) laws used by the police force on Black citizens. In speaking about the era, he argues, “Writing was a political act and poetry was a cultural weapon.” (Poetry Archive, “Linton Kwesi Johnson”).

Johnson’s style of patois used in his poetry has been read by literary critics as a way to fight back against the white English repression of Black heritage and the determination of English schools to brand Black dialects as “incorrect” or just “wrong.” The phonetic style it is written in adds to the music and protest chant aesthetic, and some academics think it creates a bridge for British-Jamaican immigrants to feel connected to their heritage and culture. Frequently, Johnson also writes poems to the memory of anti-racist protesters, strike coordinators, and socialist activists that were killed by authorities in riots and protests (British Council, “Linton Kwesi Johnson-Literature”).

As an Afro-Caribbean immigrant writer growing up during a time of social upheaval and injustice towards minorities, Johnson’s poetry stays relevant today in an England that struggles with political decisions of gentrification, immigration, and economics.

Photo courtesy of allmusic.com.

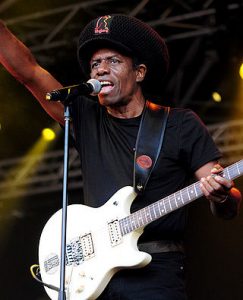

Eddy Grant

“We’re gonna rock down to Electric Avenue/And then we’ll take it higher.”

Best known for his 1982 reggae smash hit “Electric Avenue,” Guyanese-British singer Eddy Grant did more than just write chart-toppers. At a young age he was experimenting with his cultural background and putting it into the practice of his musical talents. In 1965, he created one of the first multicultural pop bands in Britain to ever find mainstream success, The Equals. The Equals were Grant, twin Jamaican immigrants Lincoln and Derv Gordon, and white Englishmen John Hall and Patrick Lloyd (Greene, “Eddy Grant Biography”).

Grant’s life of music started on 5 March 1948, in British-colonized Guyana (World Factbook, “Guyana”). He grew up listening to tan singing, an Indo-Caribbean vocal performance style of South Asian descent. When his family moved to working-class Stoke Newington in London in 1960, Grant integrated his tastes with blues, rock, and R&B (Greene, “Eddy Grant Biography”).

Grant’s contributions to music within the next decade–including multiple international singles with The Equals, the opening of his own British reggae label Torpedo, and a few solo works here and there–were cut short by a heart attack at the age of 23. He lived, but had to give up his busy lifestyle, which was deemed the cause of the illness (Greene, “Eddy Grant Biography”).

Grant refused to give up his passion, though. In 1972 he opened The Coach House, a recording studio where he helped artists signed to his new label, Ice. But he still wanted to use his own talents and released Message Man in 1977. It was a political album filled with lyrics of racial violence, neglect from the majority, and working-class struggles that Grant witnessed during his adolescence. The album flopped commercially, but still proved a springboard for Grant’s solo career. It also created a great deal of music press hype about the new style Grant was pioneering; he combined calypso with modern soul (Greene, “Eddy Grant Biography”).

The real success came with Grant’s major hit “Electric Avenue” in the early 80s, an upbeat-sounding but dark song about the 1981 Brixton Riots. The Riots were fueled by tensions between black youth and white British police, specifically over “stop and search” procedures put in place to try and stop crime, and with frustration among West Indian and East Indian residents about the declining state of life in Brixton since the end of World War Two. High unemployment among black British residents of Brixton also caused anger. Riot tensions started on April 10 when police tried to help an injured black man, but had their actions misinterpreted and were attacked. This lead to severe police patrol among the area, with up to 84 officers in the streets of Brixton at a time. After a young black taxi driver was stopped and searched the next day, riots broke out in the streets and an estimated 324 people (both rioters and police) were injured (Felix, “Brixton Riots”).

Grant emigrated to the Barbados in the mid-80s, opened a studio called Blue Wave, and dedicated his career to helping young and emerging calypso artists navigate the music scene. He also became a successful music publisher and remained in control of Ice Records (Greene, “Eddy Grant Biography”).

A witness to black working-class immigrant frustration, a man who came of age during significant changes in the ethnic landscape of Great Britain, and the musical mastermind who pioneered innovations in both traditional West Indian music and British rock, Grant remains a multitalented product of the British Empire–and his lyrics let an intuitive listener know just that.

Farrokh Bulsara (Freddie Mercury)

“Mama/Life had just begun/But now I’ve gone and thrown it all away.”

The quintessential band of Britishness, Queen generally isn’t seen as the product of Empire. However, lead singer Freddie Mercury–legally named Farrokh Bulsara–was born into a Parsi family in the British Protectorate of the Sultanate of Zanzibar, making him of direct Indian descent (Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Freddie Mercury”). Being Parsi, Mercury and his family practiced the ancient Iranian religion of Zoroastrianism, the oldest known monotheistic religion in the world. It is often credited with inspiring Christian and Islamic traditions (BBC, “Religion: Zoroastrianism”).

Parsis themselves got their name from their Persian history and are the descendants of a group of northern Iranian Zoroastrians who fled to India in the 10th century to avoid Muslim crusades. Not seeking conversion and not wanting their temples and sacred texts destroyed, these Persians found new life in India and still remain an active religious minority in Mumbai and Gujarat. Their Towers of Silence, a key part of Zoroastrian death ceremonies, are religious landmarks in these regions. As early as the 17th century, Parsis started trading with British East India Company posts, and historically were viewed as more “receptive” to European culture (Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Parsi”).

Mercury was born 5 September 1946 in Stone Town, Zanzibar (also known as Zanzibar City) in a family of Indian emigrants. His father moved the family from India to Zanzibar, since he was a clerk with the British government and got transferred to another part of the Empire. As a child, Mercury was sent to boarding school in Panchgani, Maharashtra state, India. During the school year in 1959, Mercury and his school friends formed a band called The Hectics. He was the pianist (Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Freddie Mercury”).

The Bulsara family moved to Feltham, England in 1964, after Zanzibar and Tanganyika gained independence and formed the new united country of Tanzania. They were fleeing local rebellions and protests by African residents against wealthy Indian emigrants. In London, Mercury attended Ealing Technical College and School of Art (which is now the University of West London), where he studied graphic design and graduated in 1969 (Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Freddie Mercury”). After graduation, Mercury performed as a singer with several local bands like Wreckage, Ibex, and Sour Milk Sea. Following the disbandment of these acts, Mercury teamed up with his friends Roger Taylor and Brian May, who were in a band called Smile. With Mercury at the helm as the frontman, the band changed their name to Queen and released their debut in 1973, Queen, followed closely by 1974’s Queen II (Queen Productions, “Freddie Mercury”).

While the albums initially failed to garner much attention in the United Kingdom, the album Sheer Heart Attack (1974) and A Night at the Opera (1975) lead to almost overnight success. Songs like “We Will Rock You” and “We Are The Champions,” both released in 1977, have become integral pieces of both United States and United Kingdom pop culture and sports life (Queen Productions, “Freddie Mercury”).

Queen also gained a massive following with their live shows and are often credited with starting the subgenre of “stadium rock.” Mercury was well known for his flamboyant costumes and stage presence, but was allegedly quite shy off stage and didn’t give interviews frequently. His sexuality was also constantly debated among the gossip press, as Mercury dated both women and men but never revealed much about his personal romantic life (Queen Productions, “Freddie Mercury”).

Mercury’s life was unfortunately cut short in 1991 when he died of AIDS-related pneumonia. While the music of Queen lives on in the public consciousness, Mercury’s tale of multiculturalism and symbol of the product of Empire remains relatively unknown.

Young Fathers

Young Fathers are one of the most politically-vocal rap groups since Public Enemy or N.W.A in the 90s. The group consists of Graham ‘G’ Hastings, Kayos Bankole and Alloysious Massaquoi. Hailing from Edinburgh, this outfit won the Mercury Prize in 2014 for their second album, Dead. Bankole and Hastings both were born and grew up mostly in Edinburgh while, Massaquoi was born in Liberia and moved to Edinburgh when he was four. They publicly refuse to talk to right-wing newspapers like The Sun or Daily Star and were extremely critical of the Brexit decision. Hastings commented on the Brexit vote in Dazed Magazine online: “I think a lot of people voted Leave because a lot of people are xenophobic, even if they don’t say it out loud. If you think we should go back, that’s only because you’ve had it too good at the expense of those who haven’t. Yes, it was a simpler time when people weren’t aware of other cultures or how the UK has raped half the world for its own benefit – simple, but a lie” (Bulut 1). Their social media presence solidifies their politics with posts of the band holding up a flyer stating, “Stand Up To Racism & Fascism,” and using hashtags such as: #refugeeswelcome, #dontbombsyria and #blacklivesmatter. Their past tour was called “We Are All Migrants Tour,” which featured imagery of people holding signs, pieces of paper or writing on their bodies #weareallmigrants.

White Men are Black Men Too is the third LP by the Scottish lo-fi R&B rap, Young Fathers. WMABMT is their most confrontational and political album. It is also their most successful yet receiving critical acclaim and landing on several “Best Album of 2015” lists. Compared to Dead, WMABMT is less polished but their sound has a lasting impression. Their music is gritty and aggressive, yet at the same time soulful. Similar to many other hip-hop groups, they use combination of genres to utilize unique sounds that create music that transcends genres. “Old Rock n Roll”, contains their most overt conversations of racial politics, “I’m tired playing the good black / I’m tired of having to hold back / I’m tired of wearing this hallmark of evils that happened way back / I’m tired of blaming the white man / His indiscretions don’t betray him / A black man could play him”. In “Sirens”, we see references to police violence through their lyrics and in “27” we are given some of the best melodies being interlaced with Massaquoi yelling “Black Oppression!” Although their tracks lose some of their power towards the end of the LP, this album approaches social justice through song eloquently and effectively. With textured vocals and pop potential, Young Fathers are onto something big, it’s only a matter of time.

Laura Mvula

Laura Mvula was born in Birmingham, England in 1986. She grew up in a religious household where pop music was banned, but jazz and gospel music flourished. Her rise to soulful prominence began early. After signing with RCA in 2012, Mvula released her first EP, She, and then went on to release Sing to the Moon in 2013. Her music is electric, powerful and warm. The elaborate orchestral compositions that weave their way through each song provide lush sounds. Partnered with her textured vocals, Laura Mvula’s music feels utterly refreshing. Mvula’s voice feels familiar but has a contemporary flare that makes it refreshing. Her soul is felt throughout her tracks whether through a swell or a whisper. Paul Lester of the Guardian coined a new term “gospeldelia,” a new music genre, when describing Mvula’s music. Sing to the Moon went on to reach number 9 on the UK Albums chart and was nominated for a Mercury Prize. Mvula has described the album as “The most liberating point I’ve ever been” and “a celebration of everything I’ve ever loved about music.”

Mvula’s work would not necessarily be described as political, but rather her identity cannot be separated from politics. As a black woman, blackness is central to her music and her womanhood is worn as a badge of honor. In 2016 she declared, “Black identity is really important for me- that’s what’s on my heart now and has been in my subconscious for most of my life.” Although Mvula’s music speaks for itself, it is her music videos that make her message feel fully fleshed out and visibly show her centering blackness. Her videos for, “Overcome,” “That’s Alright,” “Green Garden” and “Phenomenal Women,” feature all black dancers. This reflects a distinct choice to center black female bodies instead of using them as props like many other musicians. She provides a platform through these videos to show strength, happiness and resilience within the black community. She is boldly and unapologetically affirming who she is with tracks such as “Make Me Lovely” and “That’s Alright”. These tracks both have positive affirmations of self love and unapologetic blackness. In “She”, Mvula voices this resilience and conviction that black women must have in order to survive as “But she don’t stop” is repeated like a prayer.

Black British Queer Authors

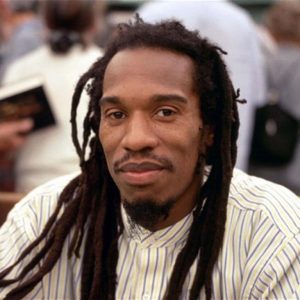

Benjamin Zephaniah

Benjamin Zephaniah is a British poet of Jamaican descent. For most of his childhood, he lived in Handsworth, a suburb of Birmingham with a heavy Afro-Caribbean and South Asian population that Zephaniah refers to as “the Jamaican capital of Europe” (Zephaniah 2017). He hated the study of poetry in school, finding it stiff, formal, and out of touch with modern life;

Benjamin Zephaniah is a British poet of Jamaican descent. For most of his childhood, he lived in Handsworth, a suburb of Birmingham with a heavy Afro-Caribbean and South Asian population that Zephaniah refers to as “the Jamaican capital of Europe” (Zephaniah 2017). He hated the study of poetry in school, finding it stiff, formal, and out of touch with modern life;

however, the discovery of spoken word poetry changed his perspective. By the time he was a teenager, he had developed a reputation of heavy civically involved by frequently attending protests and rallies and speaking eloquently on local

issues. These experiences impacted both his writing style and subject matter, and he weaves themes like identity and race into his spoken word poetry (Kay & Zephaniah 2012).

Zephaniah’s poems are both written and performed through spoken word. He has written seven collections of poetry, four novels, nine children’s books dealing with tolerance and accepting others, and eight plays. Zephaniah also sometimes sings in conjunction with his spoken word performances, and he has recorded four albums. In addition to his work as a writer, he is currently a professor of poetry and creative writing at Brunel University in Uxbridge, England. He uses his poetry and music as forms of activism, speaking out against homophobia in Jamaica as well as racism in British schools (Zephaniah 2017).

Zephaniah’s poetry is written in simple, layman’s terms, but he uses these uncomplicated words to communicate incredibly complex ideas. His poetry is a space for him to process how the history of systemic racism should contribute to how black Britons live in Britain. He has traveled throughout the British Commonwealth to perform his poetry and encourage civic action in young people, and has performed on all seven continents.

Selected works include:

“Master Master”

“The Big Bang”

“Knowing Me”

Jay Bernard

Born in 1988 in London, Jay Bernard is one of the most prol ific young black poets in Britain.

ific young black poets in Britain.

Bernard’s grandmother immigrated to the UK in the 1960’s from Jamaica. Bernard has won prestigious awards such as for the Respect Slam in 2004, and the Poetry Society’s Foyle Young Poets of the Year Award in 2005 at just seventeen years old. The Guardian named her one of the most inspirational 16-year-olds in 2004. Her first poetry collection, titled Your Sign is Cuckoo, Girl, was published in 2008. Your Sign is Cuckoo, Girl features poems that feature adolescence and the physical and emotional pains of growing up. It was awarded the Poetry Book Society’s pamphlet choice. Her most recent poetry collection is titled The Red and Yellow Nothing, published in 2016.

Bernard has read her poetry at Buckingham Palace, the Globe Theatre in London, as well as for the Royal Shakespeare Company’s Swan Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon and on a number of television programs. Bernard’s poetry demands a visceral response from its readers. Her poetry contains an element of rawness that treats immigration issues as serious problems. Bernard’s surprising and emotional poetry does an excellent job drawing attention to the issues that need it the most. Bernard was the first international Resident Writer of The Arts House, Singapore, in 2012. In addition to being a poet, Bernard is also a graphic artist. She is still currently involved in many new poetry and graphic art projects that focus on queer and trans issues.

Patience Agbabi

Patience Agbabi, born to Nigerian parents in London in 1965, is a British self-proclaimed “poetical activist” and spoken word poet (Rosenfeld). She was adopted and raised in North Wales by a white family and studied English Literature at Pembroke College, Oxford. She earned her M.A. in Creative Writing at Sussex University (Evans-Bush). Agbabi became a prominent performer in the spoken word circuit in the late 1990s and has toured extensively through Britain and abroad, in places such as Namibia, the Czech Republic, Zimbabwe, Germany and Switzerland.

Patience Agbabi, born to Nigerian parents in London in 1965, is a British self-proclaimed “poetical activist” and spoken word poet (Rosenfeld). She was adopted and raised in North Wales by a white family and studied English Literature at Pembroke College, Oxford. She earned her M.A. in Creative Writing at Sussex University (Evans-Bush). Agbabi became a prominent performer in the spoken word circuit in the late 1990s and has toured extensively through Britain and abroad, in places such as Namibia, the Czech Republic, Zimbabwe, Germany and Switzerland.

Published in 1995, her first book, R.A.W., won the 1997 Excelle literary award, and she has since authored three poetry collections amongst other works (Rosenfeld). Much of her spoken word work draws heavily on the forms, structures and canon of more traditional English poetry, and as a queer Black woman poet, she also tends to deal with a grand variety of topics, such as issues of gender, and ideas of sexual, racial, cultural and linguistic identity (Evans-Bush). Identifying as a bicultural and bisexual radical feminist, the majority of her poetry centers around these themes, and through her poetry Agbabi extends her voice in order to give one to those who might otherwise go unheard.

An overarching theme throughout much of Agbabi’s work is that of language itself. She concerns herself with how language works, who owns which words, and how forms and traditions can be made to intersect and work together.

She is also a former Poet Laureate of Canterbury for the year of 2009.

She has since performed her work worldwide on both projects sponsored by the British Council and independent engagements, and is currently on the Council of Management for the Arvon Foundation (Evans-Bush).

Some of her selected works include:

- The Wife of Baba

- Telling Tales

- Bloodshot Monochrome

- Transformatrix

- The Doll’s House

- R.A.W.

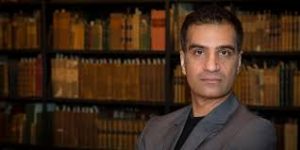

Saleem Haddad

Saleem Haddad was born in 1983 in Kuwait. His most popular novel is called Guapa and it was

released in March 2016. Saleem is an out gay man and this has inspired him to write about the different issues that the gay community faces. In his book, he writes about the story of Rasa who is going through a lot of trouble with his own identity and trying to figure out where he fits in within society.

released in March 2016. Saleem is an out gay man and this has inspired him to write about the different issues that the gay community faces. In his book, he writes about the story of Rasa who is going through a lot of trouble with his own identity and trying to figure out where he fits in within society.

Another interesting fact about Saleem is that he has worked with Doctors Without Borders and has contributed to a lot of different organizations that are set out to help people. He has a lot of interviews out talking about the struggles that he has faced being Arab and queer and how he has overcome the different labels. This transfers into a lot of his works where he has the main characters going through a lot of the same issues that he has faced within society. Saleem addresses a lot of current political and societal issues that are occurring around him in his books and that is what helps create the plotlines within his stories. Saleem meshes well with the other authors that we have researched because he has talked about. He currently resides in London with his partner.

Black British Authors

Caryl Phillips

Born in St. Kitts, Caryl Phillips moved to Britain when he was four months old and grew up in Leeds. He studied English Literature at Oxford University. Phillips says that he was compelled to begin writing because he wanted to share the story of being a black Briton. Many of Phillips’ novels and essays center around the idea of identity, of which he says race plays an important role for both himself and for Britain as a whole. In his writing, Phillips uses characters to tie a reader into the story, hoping that readers will then take their connection to a character and further it to understand the world from a new perspective. From his understanding of writing as a “political act”, it is clear to see why Phillips is such an eminent black British writer, holding over 25 literary awards. Phillips has taught at various universities across the world and is currently a Professor of English at Yale University.

Born in St. Kitts, Caryl Phillips moved to Britain when he was four months old and grew up in Leeds. He studied English Literature at Oxford University. Phillips says that he was compelled to begin writing because he wanted to share the story of being a black Briton. Many of Phillips’ novels and essays center around the idea of identity, of which he says race plays an important role for both himself and for Britain as a whole. In his writing, Phillips uses characters to tie a reader into the story, hoping that readers will then take their connection to a character and further it to understand the world from a new perspective. From his understanding of writing as a “political act”, it is clear to see why Phillips is such an eminent black British writer, holding over 25 literary awards. Phillips has taught at various universities across the world and is currently a Professor of English at Yale University.

Important Quote: “Traveling has helped liberate me from ever being tempted to view literature as a cultural product that is slavishly tied to nation.”

Century when there were significant Black populations in the country. So, in one sense, The Emperor’s Babe is a dig at those Brits who still harbor ridiculous notions of ‘racial’ purity and the glory days of Britain as an all-white nation.”

Jackie Kay

Born in Scotland to a Scottish mother and a Nigerian father, Jack Kay grew up in Glasgow after

Born in Scotland to a Scottish mother and a Nigerian father, Jack Kay grew up in Glasgow after

being adopted by a white couple. It is her adoption, along with her race and her sexuality, that drives many of the themes in her work, asking the questions “Who am I?” and “Where am I from?” Kay writes about her childhood and the experience of growing up in a white family and finding her birth parents. Though she had been writing poetry since she was 12 years old, Kay became interested in writing after a car accident in 1978 left her spending her recovery time steeped in literature. Since this time, she has gone on to write a great number of novels and poetry collections. In 2010, she wrote an autobiography titled Red Dust Road, detailing her journey to find her biological parents, a somewhat traumatic experience for Kay. Ultimately, Kay’s work centers around the “ongoing quest” of understanding personal identities and focus on the power of love. Kay has won over 20 literary awards for her poetry and both fiction and non-fiction works.

Important Quote: “I still have Scottish people asking me where I’m from. They won’t actually hear my voice because they are too busy seeing my face.”

Nadeem Aslam

Born in Pakistan, Nadeem Aslam moved to Britain when he was a teenager. The author of three novels, Aslam became a writer after leaving the University of Manchester, where he majored in biochemistry. Aslam is a believer in the process of writing and handwrites the first drafts of his novels. His three novels – Season of the Rainbirds (1993), Maps for Lost Lovers (2004), The Wasted Vigil (2008), and The Blind Man’s Garden (2013) – are all connected to South Asia, focusing on the lives of those who come from Pakistan and Afghanistan. Because he lived in Pakistan for most of his life, Aslam’s novels are sprinkled with the Urdu phrases and poetry, and Aslam says, “I am grateful for my knowledge of Urdu. I don’t just have the twenty-six letters of English, I have the thirty-eight letters of Urdu, too.” At the core of his writing, Aslam is interested in stripping away the notions of religion, nation, and ideology and looking at the people that lay underneath. Aslam is a master of prose and holds over 10 literary awards.

Born in Pakistan, Nadeem Aslam moved to Britain when he was a teenager. The author of three novels, Aslam became a writer after leaving the University of Manchester, where he majored in biochemistry. Aslam is a believer in the process of writing and handwrites the first drafts of his novels. His three novels – Season of the Rainbirds (1993), Maps for Lost Lovers (2004), The Wasted Vigil (2008), and The Blind Man’s Garden (2013) – are all connected to South Asia, focusing on the lives of those who come from Pakistan and Afghanistan. Because he lived in Pakistan for most of his life, Aslam’s novels are sprinkled with the Urdu phrases and poetry, and Aslam says, “I am grateful for my knowledge of Urdu. I don’t just have the twenty-six letters of English, I have the thirty-eight letters of Urdu, too.” At the core of his writing, Aslam is interested in stripping away the notions of religion, nation, and ideology and looking at the people that lay underneath. Aslam is a master of prose and holds over 10 literary awards.

Important Quote: “England is ‘home,’ in inverted commas. Emotionally, I think of a map in which Pakistan and England are fused. The Grand Trunk road passes through Lahore and Peshawar, drops down into the Khyber Pass, and emerges into Newcastle in the north of England. That is the ‘country’ I live in.”

Bernardine Evaristo

Born and raised in London, Bernardine Evaristo was one of eight children raised by her English

mother and Nigerian father. Originally trained in theatre during her childhood, Evaristo earned her PhD in Creative Writing at the University of London. Evaristo’s writing career took off in 1997 with her first novel that details the family heritage of a mixed-race family, Lara. To date, she has written seven novels (most in verse) and published works in numerous other genres, including theatre and poetry. In reference to her prose novels, Evaristo says, “I am an experimenter at heart — pushing the boundaries of form and content. I see myself as a storyteller who uses whatever forms seem to fit the story I want to tell.” Her work often deals with identity, focusing on the areas of race, sexuality, and immigration. Evaristo has participated in 140 international book tours, has had her work (The Emperor’s Babe) adapted into a radio play, and is a well-known literary critic. She is an steadfast supporter of representation in the arts, advocating for people of color. Evaristo is currently teaching at Brunel University London as a Professor of Creative Writing.

Important Quote: “Britain has always been multicultural, and to a greater or lesser extent, multiracial, certainly from the 16th Century when there were significant Black populations in the country. So, in one sense, The Emperor’s Babe is a dig at those Brits who still harbor ridiculous notions of ‘racial’ purity and the glory days of Britain as an all-white nation.”