Even if you haven’t heard of Hozier, you’ve probably heard his song “Take Me to Church.” Released in 2013, it catapulted the young song-writer Andrew Hozier-Byrne into the global music scene with its melancholic revelation of a revolutionary love.1 It dominated radio upon its release, becoming an alternative hit in America by 2014.2 The theme of love, in all its holy, destructive, overpowering, and gently plebeian facets, directs most of Hozier’s music. He balances this vacillating nature of love by juxtaposing the mundane with the folkloric. Additionally, his music often addresses modern movements and concerns. To tackle these two immense topics, he often turns to mythologies of millennia past. Here, we’ll look at seven of his most powerful mythological references.

7) “Take Me to Church,” Hozier

While we’re here, let’s take a closer look at Hozier’s most famous single. The lover in “Take Me to Church” rejects modern Christianity in favor of pagan worship of his beloved:

If I’m a pagan of the good times

My lover’s the sunlight

To keep the Goddess on my side

She demands a sacrifice.

Hozier returns to the theme of the beloved as “sunlight” in his song called, unsurprisingly “Sunlight,” which we’ll get to in a moment. But here he contrasts two “religions.” His experience with what he felt to be a lying, hypocritical church is revealed in the chorus: “I’ll worship like a dog at the shrine of your lies / I’ll tell you my sins so you can sharpen your knife.” But when he is with his love, his worship of her liberates him. Where he once felt condemned, he finds that “[t]here is no sweeter innocence than our gentle sin”— a sharp rejection of traditional, Judeo-Christian concepts of sin and guilt.

6) “From Eden,” Hozier

Before we get into Greek and Irish mythology, another song playing with Judeo-Christian traditions commands our attention. One of my personal favorite Hozier songs, “From Eden” immediately references the Biblical garden of paradise in its title. Its chorus nods towards the medieval concept of chivalry before the narrator identifies as the deceitful serpent of the garden:

Honey, you’re familiar like my mirror years ago

Idealism sits in prison, chivalry fell on its sword

Innocence died screaming, honey, ask me I should know

I slithered here from Eden just to sit outside your door.

As idealism, chivalry, and innocence itself seem to have lost meaning, the lover identifies as the very serpent that wedged sin into the Biblical garden of pre-historical paradise. As in “Take Me to Church,” Hozier takes an unconventional route when he suggests that the very broken nature of their love is what makes it valuable: “Babe, there’s something broken about this / But I might be hoping about this. / Oh, what a sin.”

5) “Sedated,” Hozier

But Hozier doesn’t always spend entire songs building a religious analogy. Instead, he often slips in references with clever ease:

Any way to distract and sedate

Adding shadows to the walls of the cave.

“Sedated” explores love as a destructive force by comparing it to a sedative drug. In the way that a sedative can “distract” one from the truth, so can love become a maladaptive coping mechanism, distracting a lover from the potential dangers of losing oneself in another. The allegory Hozier references here is Plato’s cave. An ancient Greek philosopher, Plato imagined a situation in which a group of people have lived their entire lives inside a dark cave. The only light comes from a fire lit behind them which casts shadows of the real world that passes by, but the cave’s inhabitants think the shadows themselves are reality.3 The “truth” sedation offers is only shadows.

4) “Nina Cried Power, ” Wasteland, Baby!

Hozier references the Allegory of the Cave again in “Nina Cried Power,” a stirring song named after American civil rights activist and musician Nina Simone. Hozier and Mavis Staples, another American activist, sing about the fight for civil rights, especially in his native Ireland:

It’s not the shade, we should be past it

It’s the light, and it’s the obstacle that casts it

It’s the heat that drives the light

It’s the fire it ignites

It’s not the waking, it’s the rising.

He uses the allegory to urge a return to reality, to see what truly creates injustice in order that we might face it directly. Building on the imagery of the fire specifically, Hozier demands that we turn from the false shades to foster the real flames of action and to face the “obstacle[s].” Only then can we rise.

3) “Talk,” Wasteland, Baby!

The tale of Orpheus has been retold countless times since Virgil recorded it in the first century BCE. The famed poet Orpheus travels into the underworld to beg for the return of his beloved Eurydice to the world of the living. The god of that realm, Hades, instructs him to travel back without looking behind him— only then will his beloved be saved. But Orpheus turns to see if Eurydice is following him, thus sealing her fate, and he returns to the world of the living without her. It captures what Hozier describes as “the lost myth of true love” in his song “Talk”— a kind of love that feels impossible and alien in our relativist day.

Retelling this story, he personifies the overpowering emotions of desperate love as… himself:

I’d be the voice that urged Orpheus

When her body was found.

I’d be the choiceless hope in grief

That drove him underground.

I’d be the dreadful need in the devotee

That made him turn around.

And I’d be the immediate forgiveness

In Eurydice.

Imagine being loved by me.

Love drives us towards desperate acts, but the end of this verse suggests that love also can be the balm of forgiveness. Most retellings do not give much space for the reaction of Eurydice to her lover’s failure. But Hozier molds an entire being in her response— forgiveness personified. “That’s the kind of love / I’ve been dreaming of,” he sings in another song (“Dinner & Diatribes”).

2) “Sunlight,” Wasteland, Baby!

Each day you rise with me

Know that I would gladly be

The Icarus to your certainty

Oh my sunlight, sunlight, sunlight

Strap the wing to me

Death trap clad, happily

With wax melted I’d meet the sea

Under sunlight, sunlight, sunlight.

The balance between water and sunlight is a struggle that both plant-owners and the characters of ancient myth deal with. The myth of Icarus recorded in Ovid’s Metamorphoses follows Daedalus, the ingenious architect for the Minotaur’s labyrinth, and his son Icarus. Exiled on the Isle of Crete, they look to the sky for escape. Daedalus fashions wings of feathers held together by wax which they use to fly away, and those who see them soaring through the sky mistake them for gods. But Icarus, in pride or joy or simple foolishness, flies too close to the sun and melts the wax off his wings. His “unlucky father” sees his feathers floating on the water below and knows his son has drowned. He buries Icarus on the shore, all the while taunted by the song of a partridge. In tragic irony, the partridge is his nephew whom a goddess had previously transformed into a bird to escape the jealous wrath of Daedalus.4

Hozier personifies the sunlight in this myth as his beloved and identifies himself as the doomed Icarus. As he so often does, he paints himself as a willing victim to the overpowering force of love.

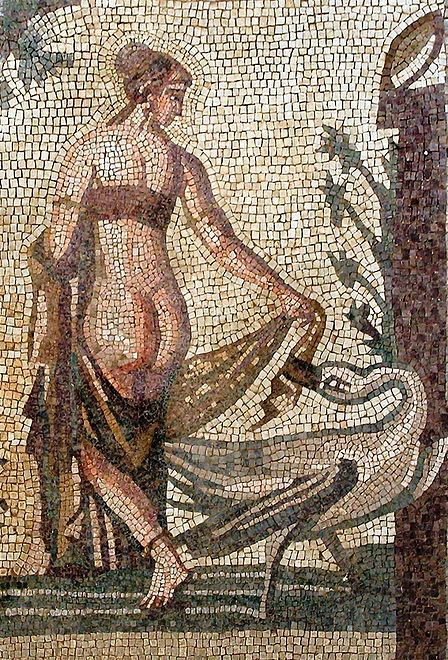

1) “Swan Upon Leda,” from the upcoming album Unreal Unearth

While Hozier often makes brief allusions to myth, he molded his newest single entirely on the frame of one Greek myth: Leda and the Swan. He released the song in October of 2022 in response to two major events: the Supreme Court ruling that overturned Roe v. Wade in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization in June 2022 and the ongoing protests in Iran concerning civil rights.5 But to understand the link Hozier is making between myth and our modern day, we must first learn about Leda.

Her story is almost too simple. Leda is a queen of Sparta, wife of King Tyndareus. But Zeus, as he often does around beautiful mortal women, finds himself taken with her. So he transforms into a swan and seduces her. Versions of the story vary in how consensual the pairing was. Leda lays two eggs from which hatch two of her daughters. In some versions, these two daughters marry into the House of Atreus, a family with a history of disordered desires and cannibalism. The story is somehow both tragically mundane and epic in consequences, fertile ground for centuries of retelling.

A husband waits outside

A crying child pushes a child into the night

She was told he would come this time

Without leaving so much as a feather behind

To enact at last the perfect plan

One more sweet boy to be butchered by men.

The song opens with this enigmatic verse, and the rest of the song is hardly more straightforward. Hozier is working on multiple levels. First and foremost, he is creating a parallel between Leda’s story and the stories of many women today. To do this, he recreates the character of Leda as a “crying child,” pushing the story sharply into an obvious tragedy and offering no room for a “romantic” spin on the tale. But this scene is a metaphor for a larger pattern of injustice against women. In mythology, the daughters of Leda become part of a grand story that spans wars and peace, empires burned and empires rebuilt. But in “Swan Upon Leda,” the tragedy continues in cycles of pointless violence: “One more sweet boy to be butchered by men.” Hozier’s cynical take on Leda’s story is not unsurprising given his track record, but neither is it gratuitous. When he released the song, he explained that he used the myth to describe “the global systems that control and endanger women” today. 5

On another level, Hozier is speaking about “occupation:”

The gateway to the world

The gun in a trembling hand

Where nature unmakes the boundary

The pillar of myth still stands

The swan upon Leda

Occupier upon ancient land

“The recent pushbacks against civil liberties and human rights respect no boundaries or borders,” says Hozier.5 Occupation implies an outsider, an imposition, an unwanted occupant. It also implies a land, a body, a violated self. “The swan upon Leda / Occupier upon ancient land:” these lines are dense. Zeus was an occupier upon Leda, Leda who was reduced to the role of land, an object in the grand purposes of epic and empire. The systems that endanger women today serve the same occupying role as Zeus.

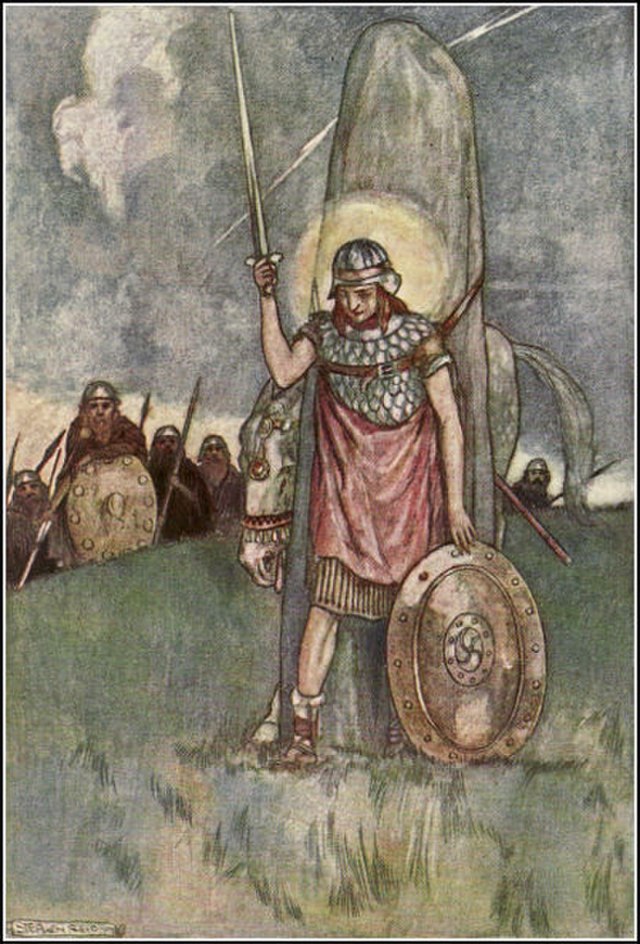

But Hozier also sings, “The swan upon Leda / Empire upon Jerusalem.” He invokes the varied history of that land and thus opens a third tier in his metaphor: political occupation. Additionally, never forgetting his home, he references Irish mythology and therefore alludes to the occupied history of Ireland: “Past where the god child-soldier Setanta stood dead,” he sings in the second verse. Known more commonly as Cuchulainn, the Hound of Culann, Setanta is a famous Irish hero and has been called the “Irish Achilles.”6 Another child of a mortal-divine pairing, his mother had him by the god Lugh Lamhfada. He died during a battle against invaders, tying himself upright to a stone when he was too exhausted to keep standing before he eventually “stood dead”— an iconic Irish symbol against occupation.

The venn diagram of topics— women today, Leda, and occupation— is complex. But Hozier is a master poet, and he does not run from the challenge. The song is slow, meditative. The listener has time to take it in and the opportunity to relisten a couple dozen times. And Hozier offers this invitation to listen closely with all his songs; he is always working effectively on many levels, musical and referential alike. He folds his music into ancient literary traditions with purpose and poise until it joins a grander mythos of gods and death, paradise and grief. But he never forgets the human.

All lyrics courtesy of AZLyrics.

1 Zollo, Paul. “Behind The Song: ‘Take Me To Church’ by Hozier.” American Songwriter. 2020. https://americansongwriter.com/behind-the-song-take-me-to-church-by-hozier/.

2 LeDonne, Rob. “Hozier and ‘Take Me To Church,’ a Four-Year Overnight Success Story.” Observer. 10 October 2014. https://observer.com/2014/10/for-hozier-and-take-me-to-church-a-four-year-overnight-success-story/.

3 “Plato’s Allegory of the Cave.” Totally History. https://totallyhistory.com/platos-allegory-of-the-cave/.

4 “OVID, METAMORPHOSES 8.” The Theoi Classical Texts Library. https://www.theoi.com/Text/OvidMetamorphoses8.html#2

5 “Swan Upon Leda.” Hozier. 7 Oct 2022. https://hozier.com/swan-upon-leda/

6 Ellis, Peter Berresford. A Dictionary of Irish Mythology. ABC-CLIO, Inc. 1987.

Cover image: Orpheus Leading Eurydice from the Underworld by Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, 1861. Public Domain. Courtesy of The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, www.mfah.org.

a The Garden of Earthly Delights by Hieronymus Bosch, c. 1490. Hieronymus Bosch, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hieronymus_Bosch_-The_Garden_of_Earthly_Delights–The_Earthly_Paradise(Garden_of_Eden).jpg.

b Ron Kroon for Anefo, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Nina_Simone_(1965).jpg

c The Fall of Icarus by Merry-Joseph Blondel, 1819. © Marie-Lan Nguyen / Wikimedia Commons. Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 Generic license. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fall_of_Icarus_Blondel_decoration_Louvre_INV2624.jpg

d Leda Mosaic. Flickr user “Ken and Nyetta”, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Leda_mosaic_crop.jpg

e Cuchulainn’s death, illustration by Stephen Reid 1904. Stephen Reid, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cuchulainn%27s_death,_illustration_by_Stephen_Reid_1904.jpg