Greco-Roman myths can be horrifying, there’s no doubt about it. Any well-read student today could give you a laundry list of Zeus’ wrongs, and the mortals are hardly better– wronged parties often respond in excessive violence. But human sacrifice, abduction, and cannibalism were not common among ancient Greeks themselves or their Roman successors. Instead, these literary horrors served to both garner the attention of audiences and build upon the specific tragic themes of a given piece of work, all while the storytellers wrestled with what justice and punishment should look like in the real world.1

The House of Atreus

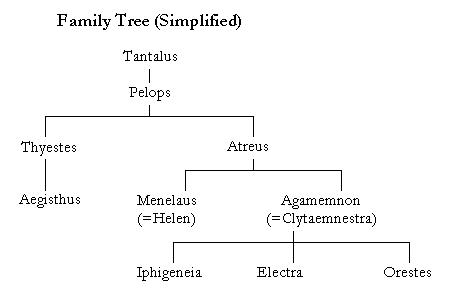

One collection of myths concerns a particularly morbidly-minded family: the House of Atreus. Their cannibalism habits begin when Tantalus, dining with the gods themselves, chops up and feeds his own son Pelops in a soup to the gods to test their wisdom and perception. While the gods damn Tantalus to Hades, they resurrect Pelops, who is later cursed by a man he throws off a cliff. The actions of these men have lasting consequences on the violently twisted House of Atreus, named after Pelop’s eldest son. 1

Atreus and his brother Thyestes fight over their father’s throne. Despite a series of deceptions and incidents of marital infidelity revolving around a certain golden fleece, Atreus eventually wins the kingdom. But when Atreus learns of his wife’s affair with Thyestes, he invites his exiled brother back into his kingdom in an act of deceptive forgiveness. Having gained the trust of his brother, Atreus kills his brothers’ sons in a gruesome rite and then serves up the boys’ flesh to their penitent father for dinner, revealing the gruesome punishment to an increasingly horrified Thyestes.

Long after the Greeks had woven the myths of the tragic House of Atreus, the Stoic politician, philosopher, and dramatist Lucius Annaeus Seneca wrote his tragedy of Thyestes. He was especially interested in what Roman justice should look like and the role of kingship in maintaining that justice.3 Thyestes’ affair with his sister-in-law is just one example of incestual relations connected to the House of Atreus. Their affair is written as pseudo-cannibalistic, making Atreus’ punishment of Thyestes not as excessive as it initially appears and arguably justified under talionic, “eye for an eye” justice. Thyestes “ate” his own kin when he lusted after his sister-in-law, so Atreus punishes him in kind.

But such violent vengeance was far from accepted by either the Romans of Seneca’s time or the Athenians. They were concerned about what fell under proper justice. Enmity required legal and civil attention, but it was limited in its vengeance by the ideals of Athenian democracy, such as the “equality, freedom, and security of each individual citizen.” 3 Violence was unacceptable. But Atreus twists justice in this myth: “Crime is owed some limit when you commit crime, not when you repay it.” 2 Moving beyond talionic justice, Atreus revels in an insatiable desire for revenge that compounds violence on violence. Today, whether Atreus’ revenge was excessive or not remains a lively debate.

Incest and murder continue to run rampant within a family driven by imbalanced desire.2 In one of the family’s final tragedies, Atreus’ son Agamemnon sacrifices his daughter Iphigenia to win back the favor of the goddess Artemis. The horrors begun by Tantalus have continued for generations. But just as Atreus finds no ultimate satisfaction after his revenge on Thyestes (“Even this is too little for me.” 2), neither do the myths of the House of Atreus as a whole end with any kind of satisfactory retribution for all their crimes. Justice appears only in the natural, tragic consequences of their unchecked violence.

Ancient-Inspired Poetry

This tale of horror and hunger remains influential to many creatives and story-tellers, such as Ohio Wesleyan sophomore and Ancient Studies major Ronan Thompson. In the three sections of his poem “A House, A Stomach,” he writes about the tragic legacy of the House of Atreus.

A House, a Stomach

by Ronan Thompson

I.

Brother,

if these walls could talk, they’d talk of hunger.

A hunger for which we have no words,

a hunger that grows the more it is fed,

a houseripping, toothful ache pulsing

from its very foundations.

A father tucks the tender flesh of his child

beneath divine tongues, and the floors savor

the taste of their own blood. This is where it all begins;

A punishment, a curse, a house, a stomach, a haunting.

A wound that festers and spreads, and gnaws,

and remembers.

II.

Brother,

It’s nothing personal, it’s just that sin drips

through the pipes, and pools on the floors,

and if you don’t drown I will.

Have you missed these halls?

Have you heard them calling you?

Come now, do not clasp my knee and weep.

It is time to eat, beneath the vaulted ceiling

of the heavens, heavy with black smoke.

We were born with the flesh of family

between our teeth—rotting and fetid.

Sometimes when I look at you, it is hard to not see meat.

III.

Brother,

Doesn’t he know he is acting out a play?

We’ve been here before, it is a memory,

or else it is a prophecy, and what difference is there, really?

The daughter is bridled before her father slits her throat,

lest he be swallowed whole.

Another child’s blood won’t sate the househunger,

but at least the Goddess has had her mouthful.

His hand is steady because the space for his blade

already exists. Flesh grown knowing its fate is to be a wound—

a wound that remembers.

Ronan Thompson is a sophomore at Ohio Wesleyan University majoring in Ancient Studies. He was introduced to classics in high school when he read Oedipus Rex and was struck by how a story from a culture and time so distant from his own still managed to evoke such strong emotions. The tragedies are his favorites and a big inspiration. He has been writing poetry almost his whole life. In his work, Ronan tries to explore the humanity of mythological characters, characters that tend to get over-simplified or flattened in modern retelling.

1 Powell, Barry B. A Short Introduction to Classical Myth. Pearson Education, Inc., 2002.

2 Fitch, John G., editor and translator. Seneca IX Tragedies II. Harvard University Press, 2004.

3 Alwine, Andrew T. Enmity and Feuding in Classical Athens. University of Texas Press, 2015.

Cover image courtesy of Unsplash

a House of Atreus family tree, CC BY-SA 2.5 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5, via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:House_of_Atreus_family_tree.jpg.

b Underworld Painter, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jason_Pelias_Louvre_K127.jpg

One thought on “Poetry: A Royal House with a Savage Appetite”