Who are the fae, and what do they want with humankind? Conceptually far from our modern, Doylean concept of tiny, winged fairies, the supernatural fae of medieval literature are much closer in physical form to J. R. R. Tolkien’s elves of Middle Earth. But more important than their physicality, the fae can be sinister, prone to abduction, and dangerously unpredictable. When they encounter these mysterious fae, the heroes of medieval Breton lais– poems of a rhyming, relatively short literary genre revolving around tales of love– are often presented with choices. While an engagement with these mysterious fae is fraught with danger for the human protagonist, such encounters also hold out the prospect of tremendous rewards. In the medieval tradition, fae — both female and male –may choose to grace a favored human, offering everything from magical purses, supplying endless wealth, to the amorous pleasures of companionship with a fairy lover

But to what degree are medieval fae merely agents of human wish fulfillment, and what do they really want with those they encounter? To answer this, I must defer to the knowledge of a quartet of fellow students who, in turn, refer largely to Lanval and Yonec, two Breton lais by Marie de France.

Marie de France

Writing in the late 12th and early 13th centuries, Marie de France was of debatably French origin. She came from a background of some means, allowing her to be literate and well-read. She may have even visited the court of King Henry II of England, to whom her lais are most probably dedicated.1

The world in which Marie de France wrote was enmeshed in cross-cultural exchange. The now-legendary figures of King Richard the Lionheart and Salah al-Din waged the Third Crusade across the Mediterranean. Marriages– and subsequent divorces– between the rulers of France and England created a tapestry of domestic and political drama with long-lasting consequences. Weaving stories in this context, it is no wonder that Marie de France wrote about faerie wish-fulfillers with a degree of cynicism– nothing in life is that easy.

The Lais

The two lais discussed here by Marie de France include protagonists who are socially struggling and their respective faerie that offers them help. Sir Lanval is set in King Arthur’s court and features a forlorn knight who encounters an impossibly rich faerie who, rather than abduct him outright, gifts him wealth. In Yonec, a lady locked in a loveless marriage– and in a tower– prays for a lover, and a faerie appears to her in a series of shifting “semblances.”1

Student Responses

Q: What are the fae up to in these lais? Let’s start with Lanval.

Morgan Vaughn: Lanval is a knight without the backing of King Arthur, despite being a relation. Though a good knight, he is generally disliked. The faerie offers him love and wealth.

Anya Shevchik: A brave, handsome knight, Lanval is forgotten, alone, and has lost all he had. He is “in a strange land,” coming from royalty and ending in Arthur’s court, broke, and with no one to support him. Lanval’s fae mistress comes and offers him all he wants– a woman and an endless purse– and all for the low price of secrecy.

Emma Weber: In both Lanval and Yonec, the fae are drawn to the main characters when they are very lonely, and some might even argue depressed. Lanval is contemplating his life while laying in a field “see[ing] nothing that pleased him.” The faerie that visits Sir Lanval brings about much desired companionship. But Lanval faces another issue for the faerie to solve: he is broke. Lanval’s faerie queen gives him an endless purse– a never-ending money supply– which is a common motif in Breton lais.

Jacob Tschertan: Sir Lanval is an unmarried, poor knight. He wants an end to the loneliness and isolation that clings to him, and the faerie provides him with endless wealth, which he can use to regain fellowship with his knightly community.

Q: What about Yonec?

MV: The Lady wishes explicitly for a knight to rescue her from her isolation, and the fairie complies. He does not take her from her room, but he does keep her company.

AS: The female protagonist, the mal mariee, is locked in a tower, alone but for her husband’s sister, with no children, friends, or hope. Due to these circumstances, a once beautiful woman loses her beauty and lives each day in despair, cursing her jaloux. Her faerie, Muldamerec, comes as a knight in shining armor, offering her love and his body for, as in Lanval, secrecy. In both Lanval and Yonec, the fairies tell their newfound partners that they have loved them from afar for a long time.

EW: Similarly depressed, The lady locked in the tower in Yonec loses her beauty due to her sorrow and goes so far as to ask for “death to take her quickly.” Although their situations differ– Lanval is free, but the lady is imprisoned in her lord’s tower– they are parallel in their deep unhappiness with their current lives. They are both lonely humans, desperate for company and connection. Here, the lady’s faerie also brings companionship.

JT: In contrast to Lanval, the protagonist in Yonec is a married, wealthy lady. But like Lanval, she desires an end to her loneliness. It is this desire for community that the fae principally address in each story. Secondary needs are taken care of as well– the faerie restores the Lady’s beauty.

Q: How do the humans respond to these gifts?

MV: Lanval uses [the wealth granted him] to win favor among his fellow knight and noble men by affording gifts and granting mercies. The faerie’s deal could have just simply made him rich, but Lanval applied the riches to his fellows, highlighting his true wish for companionship and favor.

In both of these stories, the fae do not or can not solve the whole problem, but they do give Lanval and the Lady opportunity to fix the problems themselves. Lanval receives riches, and he has to have the initiative himself to apply his wealth to earn favor. The Lady is given seemingly just love, but also it is noted that her beauty and happiness return. She is the one who flings herself out of the window, and on her quest to find dying Muldumarec, she receives the gift to make the lord forget, thus gaining her freedom.

EW: Lanval shows his worthiness through his generosity and sharing with others. The prisoner wife seems content with the situation (although she misses the faerie when he’s gone).

JT: In addressing their needs and interests, the fae enable the humans to realize the chivalric ideal.

Q: So to what degree are medieval fae merely agents of human wish fulfillment, and what do they really want with those they encounter? Is there a benevolent bone in their supernaturally beautiful bodies?

MV: While fairies do grant wishes, we see here that these fairies only provided half a solution, and Lanval and the Lady had to take action to solve the rest.

AS: To a degree, fairies are simply wish fulfillment agents for partnership and sexual intimacy. However, fairies are much more than beings for sexual fulfillment of humans. The fae work for themselves, and the gifts simply help them get what they want.

To look at other lais form this period, in Tydorel, the lady is in a happy marriage, but when the fairy knight approaches her, it is for his own desires and fulfillment; he even manipulates the happy woman by telling her she will never know joy again if she does not accept his proposal. Similarly, in Sir Orfeo, Heurodis is kidnapped for no reason other than she was beautiful, she was in a liminal location, and the fairy king wanted her.

EW: In these two stories, compared to others, the faeries are good-guy wish-fulfillers. They tell their story straight-forward and fulfill the humans’ wishes without a catch. Lanval is commanded not to tell or else the faerie won’t return, and the lady is cautioned that her beauty will kill her faerie.

In the lai of Sir Orfeo, the fae are not so clear. The faerie king is cast as a bad-guy. He kidnaps Sir Orfeo’s wife and only gives her back when he himself is tricked into a rash boon.

So the question really is– are fae as the humans’ disposal, or are they led by their own desires and motives? Perhaps Marie de France is too optimistic and overlooks the sinister side of the fae world. Or perhaps the humans, such as the old, wealthy lord and Queen Guinevere, are the bad guys all along.

JT: Although being agents of wish fulfillment is an aspect of the role fairies fill, it would be erroneous to say that that is all they are. In both stories the fairies impose on the humans a geis, not merely fulfilling their wishes, but also tacking on an obligation. The geis shows us that these fairies are not just benevolent wish granters, but have their own agenda, goals, and desires.

1 Kinoshita, Sharon, and Peggy McCraken. Marie de France: A Critical Companion. D. S. Brewer, 2012.

Cover photo courtesy of Howard Pyle, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Arthur-Pyle_Sir_Gawain.JPG.

a Anonymous author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Richard_the_Lionheart_Illumination.png

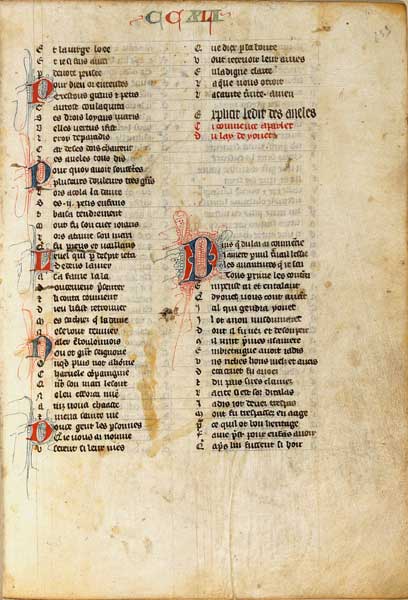

b Yonec manuscript. Bibliotheque Nationale de France, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Yonec_manuscript.jpg.

c Norbert Kenntner, Berlin, CC BY-SA 3.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/, via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Northern_Goshawk_ad_M2.jpg.