The Art and Myth of Orpheus

by Jenna Nahhas

Some stories, unlike their heroes, refuse to die. The Greek myth of the musician Orpheus and his attempt to bring back his dead wife Euridice from the Underworld has been told and retold for thousands of years. Ovid recorded the myth in Latin, it was turned into a romance in medieval times and renamed Sir Orfeo, many operettic adaptations have been performed over the centuries, and today the story is being shared once again on Broadway in Hadestown.

From an untimely death to a sung speech imploring the love and reason of the underworld gods, Ovid’s retelling of the tale of Orpheus and Eurydice masterfully combines pathos, ethos, and logos. In the Middle English poem, Sir Orfeo falls into despair and must endure both the natural world and the faeries’ otherworld. Both versions abound in imagery of the fascinating places our hero must search to recover his beloved. But when creating artwork in response to these tragic and liminal scenes, artists separated by centuries have commonly chosen to recreate one of the more peaceful scenes: the bard charming wild animals with his music. In the Sir Orfeo story, Orfeo the king leaves his castle and becomes like a wildman, living amongst nature and enrapturing the animals with his musical ability.

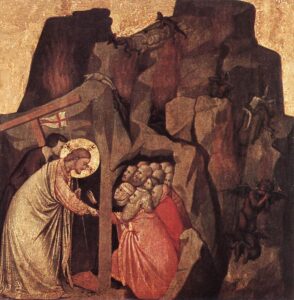

This choice of subject, a scene of musical art, lends itself to the medium, two‒ and three‒dimensional fine art. In the following six pieces, the cultural and religious contexts, be that Ancient Rome, Christian, or medieval, of each work of art influence the composition of forms within the format as well as the portrayal of Orpheus himself. Ancient Roman art based on a tragic retelling uses balance and expression to memorialize the moment before tragedy. Conversely, Medieval art based on the more happily concluded Middle English poem, although more varied, uses horizontal lines and space to exhibit a scene of isolation.

The most noticeable aspect when first observing art is how the figures are placed in the format. One difference in composition between Ancient Roman and medieval representations of the tale of Orpheus is the placement of animals around Orpheus. Both made in the early third century CE, the mosaics seen in Image 1 and Image 2 share many similarities.

Orpheus is placed in the center, holding a lyre in his left hand. As described by Ovid in the scene before Orpheus’ death, the animals literally circle the bard, a way of visually condensing their “triumphal procession”; they float in the space below, above, and on either side of him (Ovid, 423). The balanced placement of the creatures, even divided between prey and predator in Image 1, visually represents the uniting power of his music. Animals gather despite their natural status, and when a maenad tries at first to throw a stone Orpheus, his “lyre and voice united to break its force” (Ovid, 422).

In a similar manner, the relief from the fourth century CE in Image 3 places Orpheus and his lyre center, surrounded by animals. Above his left shoulder is a composite creature with the head of a human and body of an animal, perhaps a horse. As his musical prowess controls for a time even the maenads, so here he holds power over a mythological creature. However, by portraying a scene so easily remembered as connected to his brutal death, the artists invoke melancholy.

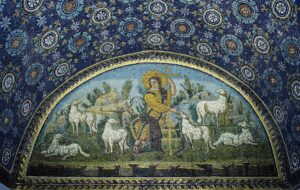

Conversely, Christian art of this musical scene is not burdened with the melancholic connotations. Concerning composition, much medieval and especially Christian art portraying this scene places figures on the horizontal axis. Although still created during the Roman Empire in approximately the third century CE, Image 4 shows a mosaic made for the tomb of a Christian, Domitilla, and therefore is conceivably composed similar to how later Christian medieval pieces would be composed.

Orpheus sits in the center, and animals gather on either side of him. The flat ground and rolling hills ground these figures on a horizontal axis. In a similar manner, the relief in Image 5 from the mid-15th century pictures Orpheus sitting on rocks while the animals on either side of him sink into the forest background but remain on the same horizontal axis as he. Once more, Image 6 features a standing Orpheus and surrounding animals in the foreground while distant buildings fade in the background. The difference in composition of Christian art from most Ancient Roman depictions of the bard can be traced back in part to their respective texts. The medieval text emphasizes the landscape into which Sir Orfeo flees, calling it a “wilderness” where he will live with “wild beasts in forests hoar” (Tolkien).

While Ovid describes the Cyprus tree picture in Image 2 as part of the “shady cluster of trees” that Orpheus sits in, he does not detail the loneliness and dirtiness of the landscape as much as the medieval poet. By placing figures on the horizontal axis as in Image 6, the artist leaves open the great sky above, increasing the sense of seclusion in which Sir Orfeo suffers. He is, before even entering the liminal lands of the faerie, in a space between earth and sky, neither who he was nor who he will become.

The character revealed by the visual aspects of Orpheus differ as well between Ancient Roman and Christian and medieval art. The Roman mosaics in Image 1 and Image 2 portray Orpheus with almost uncanny similarity. With a Phrygian cap, dark curls, dark tunic, and a red cloth covering his left shoulder, his expression is peaceful if not mournful in both mosaics. His prominent nose and delicate lips suggest a noble yet sensitive nature. His large eyes gaze upwards under heavy eyelids and thick eyebrows as though in search of divine inspiration, judgment, or rescue, subject to an outside will. Both are clad in shoes, as is the relief figure in Image 3. But while Image 3 also shows an Orpheus with curly hair and heavy eyelids, this portrayal is less youthful. As Ovid’s retelling ends in tragedy, the bard’s face carries extra weight from both his sorrow and the marble from which he is carved. Again, fate and tragedy are never far forgotten in these works of Ancient Roman art.

Christian artists varied from both the Roman representation of Orpheus and their cultural contemporaries. Unlike the previous artworks, the catacomb fresco of Image 4 as well as the Image 5 relief and Image 6 drawing all show a shoeless bard, again referencing the state in which he lived entirely in the wilderness. However, more differences than similarities can be found among these Christian artists’ work. The instrument that Orpheus plays appears as a flute (Image 4), as a lute (Image 5), and finally as a lyre (Image 6). Additionally, the position in which he sits or stands, his hat or lack thereof, and style of clothing also differ, even between the two pieces made within fifty years of each other.

Wikimedia Commons

The lack of design unity among Christian portrayals of Orpheus points to the great variation in how Christians tried to make the tale of Orpheus and Eurydice into Christian allegory as early as 370 CE. The image of Orpheus in the catacomb has been interpreted to be an early comparison between Christ as the Good Shepherd and Orpheus. Later, Pierre Bersuire similarly interprets Orpheus as an allegory for Christ, descending into Hell/Hades to save the sinner/Eurydice. But he is not always so compared. Giovanni del Virgilio writes that Orpheus is a wise man who, once having “lost profound truth,” humbly reconciled himself to God (Christian mythographic handout). Humanist William of Conches argues that the bard “stands for wisdom and eloquence,” but not Christ (Christian mythographic handout). The emergence of Christianity within the Roman Empire and its preeminence in Europe during the middle ages led to this great variety of Orpheus allegories.

The connotations of recreating the scene of the Thracian bard charming the animals differs significantly depending on the time period and culture in which the artist worked. In Ancient Roman art, Orpheus’ death looms, and his life is suspended in the art in a moment of beauty and balance. In Christian and medieval art, Sir Orfeo’s isolation, while complete, is not the end; his figure is in movement, far from its final days and eternally debated by Christian scholars. Portraying a tragic hero or a king in seclusion, artists were driven by a tale that storytellers have repeated and will continue to repeat for millennia. Whether Orpheus or Sir Orfeo or any other character lost in liminality and desperate to find their love, the Thracian bard lives on.

Works Cited

Attributed to circle of Baccio Baldini; circle of Maso Finiguerra. Orpheus charming the animals, in a landscape crowded with animals and bird listening to his harp [left]; Animals, birds, fish and mythological creatures including a mermaid gathering by the shore to hear the music of Orpheus. c. 1470-75. Artstor, library.artstor.org/asset/AGERNSHEIMIG_10313157917 Eastern Roman Empire, near Edessa, European; Roman Empire; Eastern Roman Empire.

Orpheus Taming Wild Animals. 204 A.D.. Artstor, library.artstor.org/asset/AMICO_DALLAS_103843516

Good Shepherd (Christ as Orpheus). 3rd or 4th century. Artstor, library.artstor.org/asset/SCALA_ARCHIVES_10310196969

Luca della Robbia. Panel from the Campanile; Orpheus (Music or Poetry). 1437-1439. Artstor, library.artstor.org/asset/SCALA_ARCHIVES_10310197443

Orpheus and the animals mosaic. 200-250, 3rd century, Image:Summer 1971. Artstor, library.artstor.org/asset/BRYN_MAWR_955__955_19070283

Ovid. Metamorphoses. Translated by David Raeburn, Penguin Books, 2004. Relief: Orpheus with the Animals. 4th C. A.D. Artstor,

library.artstor.org/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822000305597

Tolkien, J. R. R. “Sir Orfeo.” All Poetry, https://allpoetry.com/Sir-Orfeo. Accessed 22 January 2022.

One thought on “The Art and Myth of Orpheus”

Comments are closed.