We’d expect literary works from differing cultures to mirror that in their writing, however, The Iliad and The Song of Roland are more similar than expected. In their most basic explanations, both texts retell deeds—both good and wicked—that were carried out by men who fought in wars. It is through the innovation of the poets that their distinct and fanciful characters took shape, each drawing on the prevailing attitudes of the times in which they were performed. In The Iliad, what was probably a case of raiding and plundering across the Hellespont by Bronze Age Greeks became the story of a war that began because the most beautiful woman in the world was abducted, and the presiding king had a rage that could not be assuaged. In The Song of Roland, the historical defeat of a Carolingian rear-guard during an engagement with renegade Basques at Roncevaux Pass is transformed into an epic struggle between the Frankish forces of Western Christianity and the Saracen forces of Eastern Mohammedanism—the center of which is a lesson on how to fight and die well.

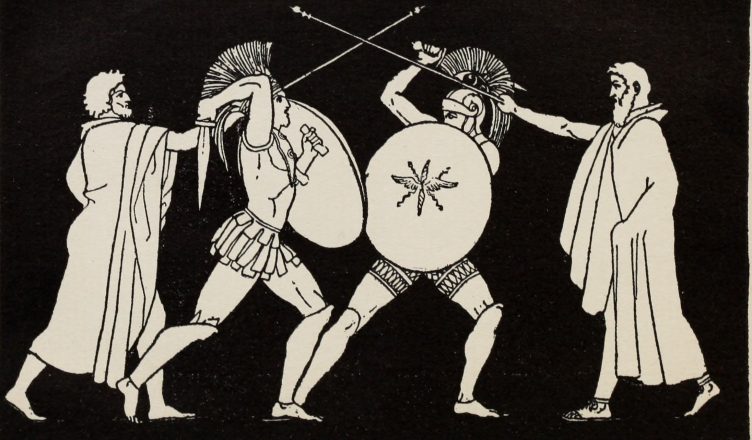

Neither poem shies away from depicting war as it is—brutal and bloody. Questioning the morality of war, however, is not essential to either poem. What the Homeric and Medieval poets are more concerned with is the human response to an unquestioned reality; that is, how do different characters act in the face of confrontation, and what can readers learn from their example? Achilles and Charlemagne teach us that a faithful companion will not let one die in vain. Oliver and Nestor show us that the best way to tackle an obstacle is with wisdom’s graces. Roland and Hector stand as a warning for brash actions; they not only affect you personally but those around you as well. If war is the centerpiece upon which both poems rely, the characters are the details that keep us engaged. The stories are told through their actions, and the wars are conduits through which they are driven to act.

Another running theme in both epics is the respective characters’ commitment to some modus operandi. In The Iliad, the Achaeans and Argives view the Trojan War as an opportunity to win glory for themselves, and it is this preoccupation with glory and fame that leads to Achilles’refusal to fight until his honor is restored. Eventually Achilles will conclude that the personal honor accrued by the spoils of war is trivial when compared to honoring a friend—in this case, Patroclus. Avenging the death of Patroclus becomes his new motivation for reentering the conflict. By committing to this new goal, however, his death at Troy is sealed, as it had been foretold that Achilles had too choices—stay, fight, and win eternal glory at the price of a shortened life, or go home, live long and prosper, but die ignominiously. Like any good hero, he chose the former.

In a similar vein, Roland sees the rear-guard action as an opportunity to demonstrate his commitment to the feudal principles that guide the actions of the Twelve Peers, even if doing so means that he will put his comrades’ lives in jeopardy. Like Achilles’ refusal to fight for Patroclus, Roland’s refusal to sound the horn and call for reinforcements that would have saved both his life and the lives of his fellow knights is the binding choice that will seal his fate. Like Achilles, Roland chooses to stand and fight despite the impossible odds.

The idea of facing your fate rather than circumventing it is the most central theme to both The Iliad and The Song of Roland. Two remarks showcase fate as the major theme in these works: Oliver’s remark to Roland —“Charles will never again receive our service”—and Achilles’ resigned answer to his horse, Roan Beauty, when the latter informs him of his impending death—“I know, well I know— I am destined to die here, far from my dear father, far from mother. But all the same I will never stop till I drive the Trojans to their bloody fill of war!” It is not only Roland and Achilles who have to reckon their fates with their actions; for the Franks, Saracens, Argives, and Trojans, the unavoidable end and the dread of its ceaseless approach is never entertained with as much concern as how the individual arrives at it.

Both poems come to an end poignantly with the deaths of Achilles and Roland, but without any sense of finality. By The Iliad’s final chapter, the walls of Troy still stand and the Greeks have yet to reclaim Helen. Similarly in The Song of Roland, the remaining Franks predict future bouts of conflict with the Saracens. Though the stories are over, the epic worlds in which they lived survive as settings and backdrops for later poets. It is as if the poets themselves intended that the words they had sung would continue to be taken up, in one form or another, long after their own performances had ended.