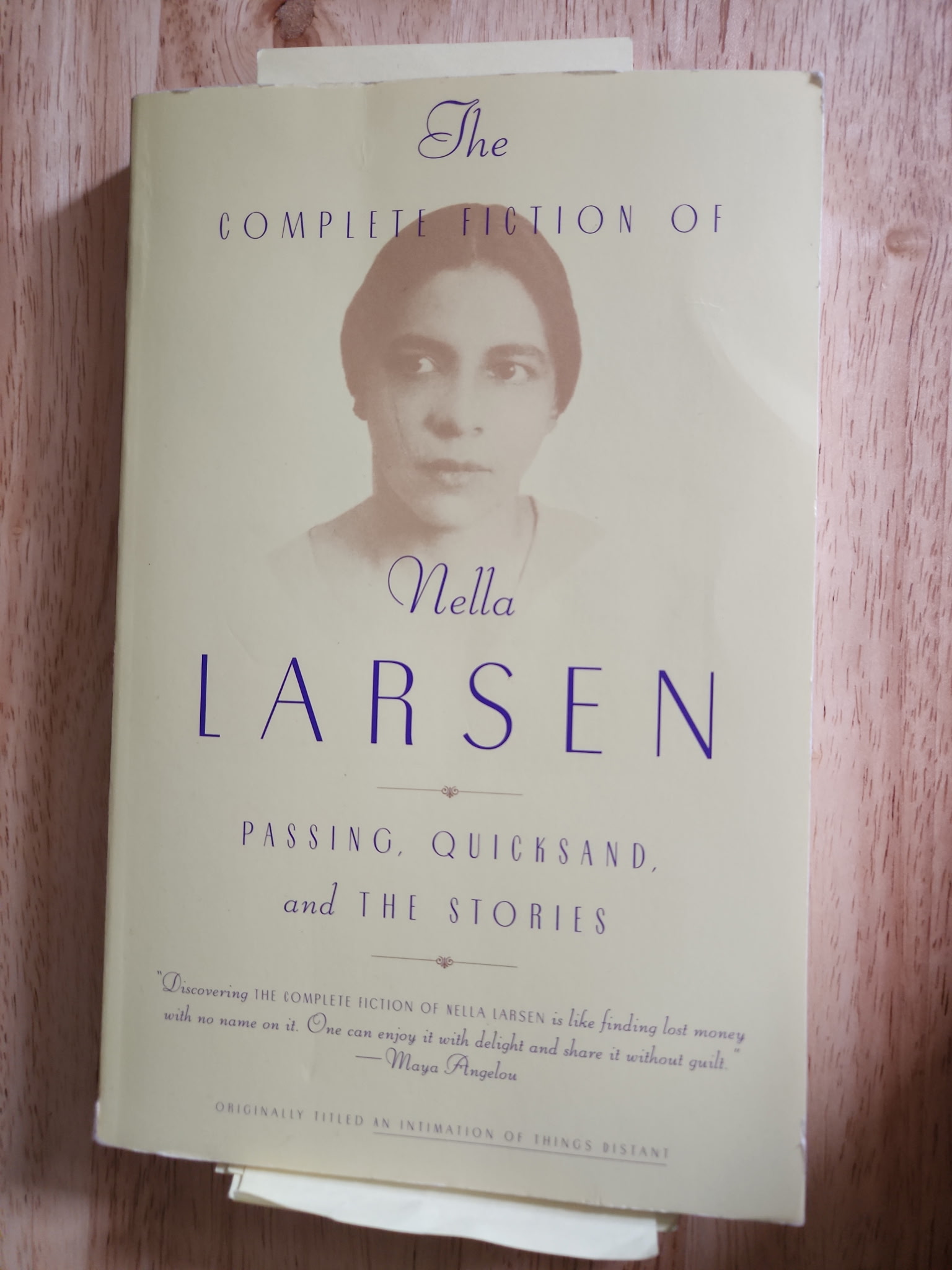

The Complete Fiction of Nella Larsen was originally titled An Intimation of Things Distant. It consists of five fiction stories by Nella Larsen that were written in the 1920s during the Harlem Renaissance, which was a movement to foster Black culture and pride through literature, art, and music. The pieces in her collection discussed tensions and hardships of the Black middle class in Harlem during the 1920s: restlessness, isolation, searching for belonging, psychology, marriage, race, and the complexities of having mixed-race heritage.

It is important to continue to shed light on Black history, culture, and the Black experience. I hate to use the worn-out saying: “This is relevant now, more than ever!” However, it really is true now as the current administration has threatened to erase the history of people of color, especially of Black persons. They want to achieve this by removing diversity and inclusion programs, and trying to ban the teaching of America’s history of slavery, and prominent Black figures from schools across the nation. If Black history is not taught to future generations, then millions of people will be erased. Black people have been erased throughout history long enough, and it is outrageous how it can possibly still be seen as permissible in America today.

I wanted to highlight two of Larsen’s fiction pieces. One of which is titled “Freedom” and is a short story about a man who wrestles with the blissful independence and the guilt of leaving his wife. The second story is her most widely acclaimed novel titled Passing, which is about the deterioration of a woman’s marriage, and sense of herself when her childhood friend who is passing for white returns to Harlem. These two stories in particular are a couple of my favorite fiction pieces from Larsen, and they both have very similar themes that drive their stories. I love these two stories because of the way they bend reality and the heart-wrenching, thrilling descriptions of the protagonists’ struggle to hold onto their sanity. Both stories further explore love and its misfortunes in a compelling, unique way as the characters face many unexpected challenges.

“Freedom” centers around a man in a passionless marriage who is away for a friend’s funeral when he is overcome with an unprovoked fervent hatred at the thought of his own wife. This feeling urges him to break away from the confines of being in his marriage, and to travel and live independently. However, after one year he begins to long for his wife, but is already consumed by the pleasures of adventure and a life of traveling on his own. Then, after a second year of this roving life, he learns the disturbing truth that his wife had passed away giving birth to his child just after he had initially left her. From then on, his desire for his wife grows erratically as the man begins to lose his sanity. His torment ends when he decides to “join his wife” and ends up stepping out of a window and falling to his death.

This story begins very ambiguously and jumps right into a moment of tension as Larsen writes, “He wondered, as he walked deftly through the impassioned traffic on the Avenue, how she would adjust her life if he were to withdraw from it” (Larsen 13). We never learn the names of the man, his wife, nor of any other person connected to either of them. This six-page story rapidly flows through two years of a man grappling with contradictory feelings towards his wife and himself. It is jarring and thrilling to read, and becomes more unhinged as the man’s sanity falls apart.

However, my only critique is that the ending felt like an awkward rush to get to the man’s death. When the man succumbs to his delusions and desires to be with his wife again, every action he makes is noted plainly, and starts to sound like a list when I would much rather be moved by more illustrative language as the pivotal, compelling last moments of the man’s life plays out. I will also admit that I felt as though the man did not receive the proper consequence for his past misdeeds. He abandoned his wife for no sensible reason, the wife who later died giving birth to his child, but the man went on to find another lover and travel and enjoy his life. Then, when he wanted his wife back, he was able to escape the burden of his tormenting delusions by falling from a window to his death. I am left with the feeling that this man never fully grasped the pain he caused his wife, and that he was just allowed to escape his problems every time they became uncomfortable. Although this story is fascinating, and conveys the hardships that may come with love and marriage, I am left wanting more from the ending.

“Nella Larsen” Collections – Get Archive

Passing follows a Black woman named Irene Redfield who lives in Harlem in the 1920s. On the one day that she decides to pass for white, she encounters her childhood friend Clare Kendry who has been passing for white for years, and is married to a viciously racist white man named John Bellew. Clare and Irene have many tense and uncomfortable interactions with each other in regards to race, passing, and the different desires they have in their life. Clare is fervently devoted to maintaining a friendship with Irene, even though Irene thinks that this is dangerous to do. As Clare grows less affectionate towards her husband, she becomes more present with Irene and Irene’s husband Brian. Irene, on the other hand, despite her alluded desire and attraction towards Clare in the novel’s subtext, starts to despise Clare’s presence. She worries that Clare will upend her ideal normal family and steal away her husband and kids.

A brief but important development in the story occurs while Irene is on a walk with a friend who has darker skin. Irene bumps into John, who is eager to greet her, but upon seeing Irene’s friend, he stands frozen and distraught with his outstretched hand, and after this moment it is apparent that John has surmised that Irene is Black. Irene incessantly worries about what John will do now that he knows that Irene, his wife’s best friend, is Black. As the story progresses, Irene’s sanity and sense of reality seems to unravel as she becomes more detached from her routine life, which appears to be slipping away from her control. Irene’s worries come to an abrupt halt however at a party with friends, when John barges into the party angered by the knowledge that his wife is Black. John steps towards Clare and she suddenly falls out of a window. The reader is left unaware if Clare’s fall was an accident, a suicide, or if she was pushed on purpose. In the brief event of Clare’s fall, Irene is described as being “maddened” by Clare’s typical smirk which compelled Irene to run towards Clare; “her terror tinged with ferocity, and [lay] a hand on Clare’s bare arm” (Larsen 271). This suggests that the vulnerable moment that Clare was in provided Irene with an opportunity to act on her suppressed anger towards Clare. Thus, it is possible that Irene had some reason to push Clare, even though Irene herself does not want to admit this to herself, so it is left up for the reader to decide.

The ending of this story was fitting to me because the ambiguity conveyed the complexities of Irene’s relationship with her husband, and with Clare. There is also ambiguity in both Irene and Clare’s relationship with race as they both had passed for white in their lives and weighed the advantages of it. Clare was illustrated as a problem, a bad seed, some alluring threat to Irene and her perfect family. I think her fall, the ridding of this threat is effective as it does not seem morally commendable for one to succeed in life by deceiving people, and trying to take things from anyone, especially one’s friends, just to gain a more comfortable life for oneself. However, in the last moments of Clare’s life she seemed like a helpless, lost creature that may have deserved mercy but it was too late for her. The threat of Clare disrupting Irene’s life any further was extinguished once her body hit the snowy ground below the apartment complex.

It is fascinating how these two stories have so many things in common. For instance, both stories involve a troubled marriage; end with the death of the person causing the disruption in the marriage as characters in both stories fall out of a window to their deaths; the protagonists are burdened with restlessness; falling out and back in love with their partners; both protagonists contemplate the death of the person causing the disruption before their deaths occur; and they both deal with the destabilization of their sense of reality and sanity. I got this collection after loving the film adaptation of Passing, and I loved all the fiction pieces in this collection, and how they conveyed the Black experience, and the mental strains that racism can put on people. I would highly recommend this book to anyone interested in any of the themes that I have mentioned. This collection will not fail to stir your soul and make you reevaluate what love means to you, and what you think is important in your life!