“Great art is the outward expression of an inner life in the artist, and this inner life will result in his personal vision of the world.” – Edward Hopper

I consider myself a lover of art in all its forms, but the way I engage with, enjoy, and often admire each is different. When I read a book, short story, or poem, my brain sparks up with thoughts and ideas, working to mentally highlight the passages I simply need to remember or to make note of the ones I would have written differently. When it comes to the visual arts, though, my enjoyment is far more passive. I paint as a hobby, but I’m not under any illusions of having talent or even beginning to comprehend all the technique and skill required by the craft. I can’t imagine how many hours of work are behind a painting or sculpture, or how those hours were possibly spent–but I find in the visual arts the incredibly freeing and delightful possibility of staring at a piece for the same amount of hours without a single concrete thought in mind–an indecipherable admiration for something I cannot begin to understand. Most times, the pieces I fall in love with seem to creep up on me–they make themselves noticeable and never stop doing so, ever-puzzling mysteries I can’t help but love to never quite figure out.

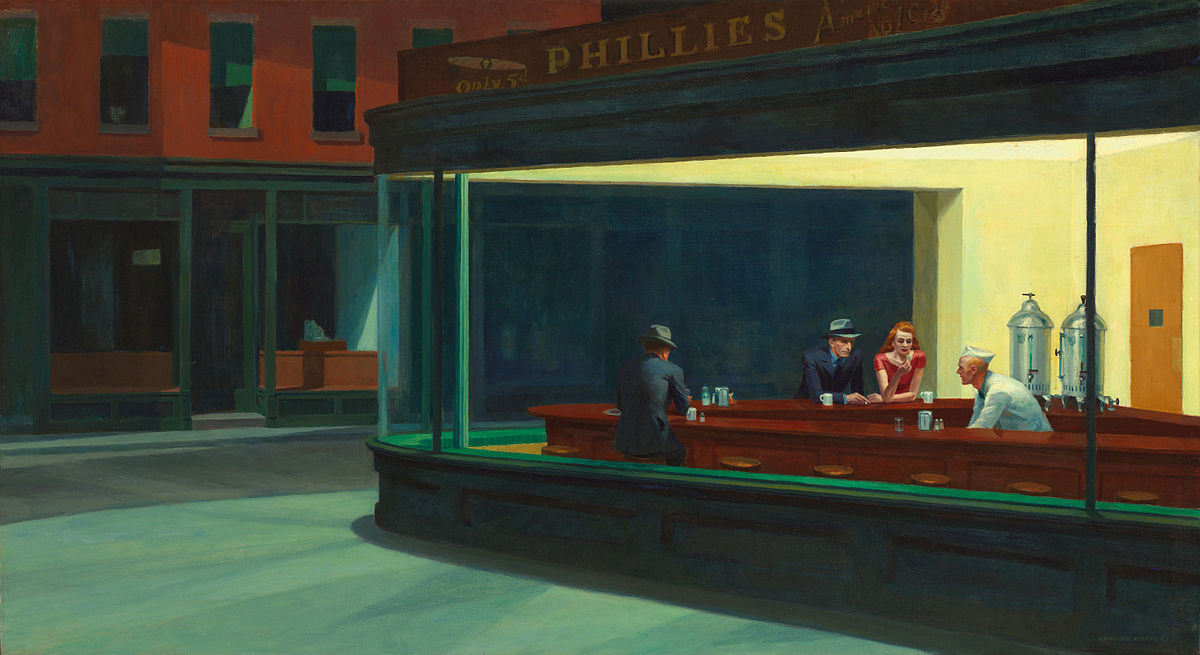

The first time I saw Edward Hopper’s painting “Nighthawks” was in fifth grade art class. I was ten years old, and like most ten year olds I didn’t have too many complex thoughts about loneliness, alienation, and the predicament of urbanity and modernization. And still, I remember with striking clarity the quiet melancholy I felt when I first looked at that painting, the same melancholy I still feel at twenty, now aware of the sentiment behind Hopper’s piece. “Nighthawks” is an oil on canvas piece completed in 1942, part of the American realism movements, and the painting portrays an almost-empty diner in a New York City intersection, where four people gather under the space’s bright lights amongst the darkening nighttime. The painting is a reflection of the solitude that often looms over life in cities, where everyone can be so cluttered together as the population grows and world around modernizes, and yet taken over by expanding loneliness.

When I looked at the painting for the first time, I didn’t know any of this. It wasn’t, to me, a commentary on anything; I couldn’t have recognized the cumulative months and years of studying, training, and working necessary to get to such a result. I was also probably too young to recognize why it got to me so much. Over the years, I learned some more about Edward Hopper and grown to admire his work far beyond “Nighthawks,” and there’s a specific quote of his that has really illuminated what it was about the piece–and maybe the visual arts in general–that broke down all the supposed barriers between us and made me feel it so deeply, so easily: “Great art is the outward expression of an inner life in the artist, and this inner life will result in his personal vision of the world.”

“Nighthawks” is a masterfully crafted painting, shows beautiful use of the oil on canvas technique, careful thought on color and composition, and a sensitive reflection on the sentiment looming over the United States in the beginning of the 1940s. But none of that is why it got to me when I first saw it, nor why it remains, ten years later, my absolute favorite painting. The heart of “Nighthawks” is the utter, unapologetic humanity in the final composition of every brushstroke. There is simply something utterly recognizable in the quietness of the night depicted–something that is not specific to a decade or a country. Many call it a sad painting, and maybe it is; personally, I tend to be very optimistic–to me, it is more of a piece about sadness. I look at the moment portrayed in the painting as a rare, quiet depiction of humanity. Some could in a single glance see in it pure loneliness, melancholy, nostalgia, suffering–to me, “Nighthawks” is the frozen frame of the intense interior lives and impossibly real emotions every single person is bound to inherently, inevitably have. It is not defined by a single word or sentiment, but instead that instance is so masterfully depicted by Hopper, with such utter honesty, that whatever feelings foreground our own self can be so effortlessly reflected in the strangers that become real in “Nighthawks.”

Hopper’s quote was so crucial for me to understand what I loved about the painting because of this exactly. Thinking of it as the “outward expression of an inner life in the artist” truly illuminated why the emotion behind it is so spectacularly tangible. It is Hopper’s vulnerability in portraying his own feelings and most internal dread about the world he inhabited that allows for each person to see themselves reflected on canvas–that allowed me, at ten years old, to see some unrecognizable thing of myself in it, and, at twenty, to recognize my own optimism in the sadness captured by Hopper’s undeniable talent.