Situated squarely between mainland Greece, Turkey, and Crete, the Cycladic Islands sat at the heart of the Bronze Age Mediterranean world. The spiral-shaped volcanic island of Thera (now Santorini)—the southernmost of the Cycladic Islands and the closest to Crete—was home to the city of Akrotiri, comfortably nestled atop a rocky cliff face. Akrotiri was a wealthy, seafaring city, originally established as a small fishing village c. 4500 BCE.1 The city flourished due to the ideal location for trade and its production of copper and saffron, quickly becoming a key player in the Bronze Age Mediterranean.2 The resulting society was a confluence of the Cretan, Near Eastern, and uniquely Cycladic cultures of the people that lived, worked, and worshiped there. 3

Most citizens of Akrotiri lived in communal housing blocks, similar to apartments or townhouses, and cooked meals in shared kitchens. They gathered together in public squares to partake in community-wide religious rituals.4 Those with more wealth lived in multi-story mansions with large windows facing out to the busy, narrow streets, and kept their pantries well stocked with wine and olives to host guests in large dining rooms.5 Every household had the conveniences of indoor plumbing and a built-in mill.6

Nearly all of their buildings, both private and communal, were lavishly decorated with painted frescoes. Lush landscape scenes transform cramped rooms into open meadows or ship cabins decorated with vases of flowers; women in elaborate costumes pick saffron under the watchful eye of a goddess attended by monkeys and griffins, while boys carry bundles of fish and practice boxing. According to archaeologist Christos G. Doumas, in his brief archaeological guide of Akrotiri: “There is hardly a house without at least one room decorated with wall-paintings.”7 Life in Akrotiri would have been like living in a city-wide art gallery, with every space imbued with deeper meaning through the scenes on the walls.

Sometime around 1500-1450 B.C.E. Akrotiri’s time as a prosperous trade hub came to an abrupt end when the volcano erupted, burying the once bustling city in a blanket of pumice and ash.8 One can still see the layer of black charcoal sandwiched between the modern city and the gray stone of the cliff. The archaeological evidence suggests that the city was evacuated prior to the eruption, as people were likely warned by a series of earthquakes leading up to the blast. Very few personal possessions or valuables have been found at the site, aside from items such as furniture which would be too heavy to carry, and no bodies have been unearthed that were killed as a result of the eruption. 9

Unlike the later eruption of Vesuvius, which killed upwards of 16,000 people, it seems that the citizens of Akrotiri were not caught unaware. The cloud of pumice and ash, rather than raining down destruction on the citizens, acted as preservationist for their paintings. The eruption on Thera maintained the vibrancy and detail of hundreds of square meters of frescoes, and that is only what has been uncovered so far.

The Forgotten Goddess of Thera

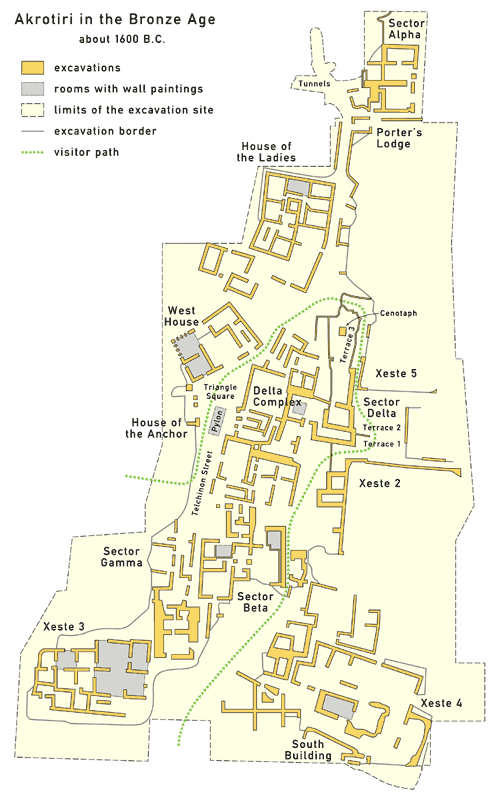

One of the most remarkable series of frescoes can be found in Xeste 3, one of the large multi-story structures found at the site sometimes referred to as “mansions.” These include a scene of a bleeding shrine where a woman sits and tends to a wounded foot, and a depiction of a seated goddess overseeing the harvest of saffron.

Many of the frescoes throughout the city depict religious rituals and scenes. Archaeologist Dr. Nanno Marinatos has identified at least seven shrines throughout the city with associated frescoes.10 The fresco programs in Xeste 3 are particularly interesting because of the Goddess and her acolytes, as she is the only confirmed deity depicted on the island. The imagery associated with the Theran goddess is strikingly consistent with goddesses depicted elsewhere in the Mediterranean, leading archaeologists to believe they may be depictions of the same, widely worshiped Bronze Age deity. She may even be a figure who we are still familiar with today.

Since the discovery of the frescoes in Xeste 3, academics have been drawing connections between the scenes depicted and the later Greek deities Demeter and Persephone, mainly due to the associations with youth, nature, rebirth, and the protection of girls and young women.11 12There have also been clear connections drawn to contemporary Egyptian and Assyrian deities with similar associations.13 Cretan art also frequently depicts a similar goddess, attended by animals and female worshipers.14 This may have all been depictions of the same goddess, who would have been easily recognizable to an ancient, and likely well traveled, audience. This mystery goddess is often referred to as Potnia, the name of a goddess frequently found in Linear B inscriptions who has similar natural associations.15

The Bleeding Woman fresco is positioned directly above the adyton (the innermost part of a shrine, literally “not to be entered”) on the ground floor. Due to its position in such a sacred part of the building, it can be assumed that the scene depicted is of particular significance. It is generally believed that the Bleeding Woman is a depiction of the same Seated Goddess that is portrayed in the room above, and together the frescoes depict a mythological narrative centered on the deity. 16

Could it be that, after fleeing the destruction of the island, the citizens of Akrotiri brought their goddess with them, and pieces of her story can still reach us through stories of Demeter and Persephone? Or was she already being worshiped beyond the island before its destruction, carried around the Mediterranean alongside the city’s other exports? It has even been proposed that the Xeste 3 frescoes represent the story of the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, as their painters would have presumably been familiar with the orally transmitted poems that would come to be compiled under Homer’s name.17 It is impossible to know for certain, but there is still a lot of Akrotiri left to be excavated. More information about the goddess might be waiting just beneath the ash and stone. In 2019 a large cache of artifacts was discovered in the House of Desks, a neighbor of Xeste 3, including a Protocycladic marble figure in the shape of a woman, encased in a wooden box with a bright red interior, a color closely associated with the Seated Goddess.18

Though there are still unanswered questions about who and how exactly they worshiped, it’s clear Akrotiri was bustling with women and girls of all ages working to serve their deity. Young girls, often neglected in later Greek art, were depicted overseeing rituals connected to some of the most important parts of life in Akrotiri, including seafaring and the crocus harvest. The frescoes give us an intimate glimpse into that civilization, seen through the eyes of those who built it; the landscapes and the people that inhabited them, all awash in color and bursting with life.

- Doumas, Christos. Santorini Archaeological Guide. 10. ↩︎

- Knappett, Carl, Tim Evans, and Ray Rivers.“Modelling Maritime Interaction.” 1016. ↩︎

- Brink, Jessica Hendrika van den.“The Global Village.” 67. ↩︎

- Palyvou, Clairy. Akrotiri Thera: An Architecture of Affluence. 29. ↩︎

- Marinatos, Nanno. Art and Religion in Thera. 23. ↩︎

- Doumas, Chritos. Santorini Archaeological Guide. 14. ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Marinatos, Nanno. Akrotiri and the East Mediterranean. 25. ↩︎

- Palyvou, Clairy. Akrotiri Thera: An Architecture of Affluence. 175. ↩︎

- Marinatos, Nanno. Art and Religion in Thera. 22. ↩︎

- Jones, Bernice “A New Reading of the Fresco Program and the Ritual in Xeste 3” ↩︎

- Marinatos, Nanno. Art and Religion in Thera. 80. ↩︎

- Brink, Jessica Hendrika van den. “The Global Village.” 25. ↩︎

- Marinatos, Nanno. Akrotiri and the East Mediterranean. 109. ↩︎

- Kopaka, K. “A Day in Potnia’s Life: Aspects of “Potnia” and Reflected “Misstress” activities in the Aegean Bronze Age.” ↩︎

- Marinatos, Nanno. Akrotiri and the East Mediterranean. 124. ↩︎

- Jones, Bernice “A New Reading of the Fresco Program and the Ritual in Xeste 3” ↩︎

- Machi Synodinou, “New Unique Finds in Akrotiri Excavation.” ↩︎

Featured Image- “Spring Fresco” photo courtesy of Paolo Villa licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Archaelogical map courtesy of Santorini.com

“Seated Goddess” photo courtesy of Zde licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0

“Adorants Fresco” photos courtesy of Zde licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0

“Saffron Gatherers” photo courtesy of Zde licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0

“Ship Fresco” photo courtesy of Zde licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0

Photo of recent excavation courtesy of the Greek Ministry of Culture, 2020.