Written by Carrinna Muncy

“Goddess, sing of the cataclysmic wrath of great Achilles, son of Peleus.”1 This is the first line of Homer’s Iliad, which sets the tone of the epic. The Iliad is a story of Achilles’s rage and the consequences of it, but Achilles’s story extends far beyond Homer’s epic. So, where does it end? Where does the famous “Achilles heel” come in? To find out, we need to examine the ever-changing nature of Greek myths.

Achilles in Homeric Texts

Homer’s Iliad is by far the most well known piece of literature that deals with Achilles. Compiled in the 8th century B.C from an earlier oral tradition, it is also one of the oldest surviving texts that mentions the character. The Iliad recounts a short period of time set towards the end of the Trojan War, a battle between several Greek city-states and the kingdom of Troy. It details an argument between Achilles and his fellow Greek commander, Agamemnon, in which Achilles is slighted, and in turn refuses to fight any longer. Given that he is one of the best Greek fighters, this is an issue, especially when Achilles asks his mother—the sea nymph Thetis—to call in a favor from Zeus, and turn the tides of war further into Troy’s favor.

Eventually, Achilles joins the battle again, but only after his closest companion, Patroclus, dies. He is killed by the Trojan Prince Hector after donning Achilles’s armor and fighting in his stead to inspire the Greeks. Achilles then goes on a warpath in his grief, killing Hector, prince of Troy and killer of Patroclus, and desecrating his body by dragging it around the city for days on end. The Iliad ends with the return of Hector’s body to King Priam, his father, after he supplicates Achilles for the body.

This is where the Iliad ends, but where and how does Achilles meet his end? Technically, his death is predicted in the Iliad’s text. Achilles reveals that he knows he is fated to die in Troy, based on a prophecy told to him by his mother. With his final breaths, Hector also predicts that Achilles will be killed by Paris and Apollo. The next we hear of the hero’s death from Homer is in the Odyssey, when King Nestor—who fought alongside Achilles—tells the son of Odysseus that Achilles died in Troy. Later in the Odyssey, the spirits of Achilles and Agamemnon have a conversation about their deaths, and we learn that there was a fight for Achilles’s corpse, and that after death, his ashes were mixed with that of Patroclus, and that his burial mound was at the Hellespont.2

The Achilles Heel

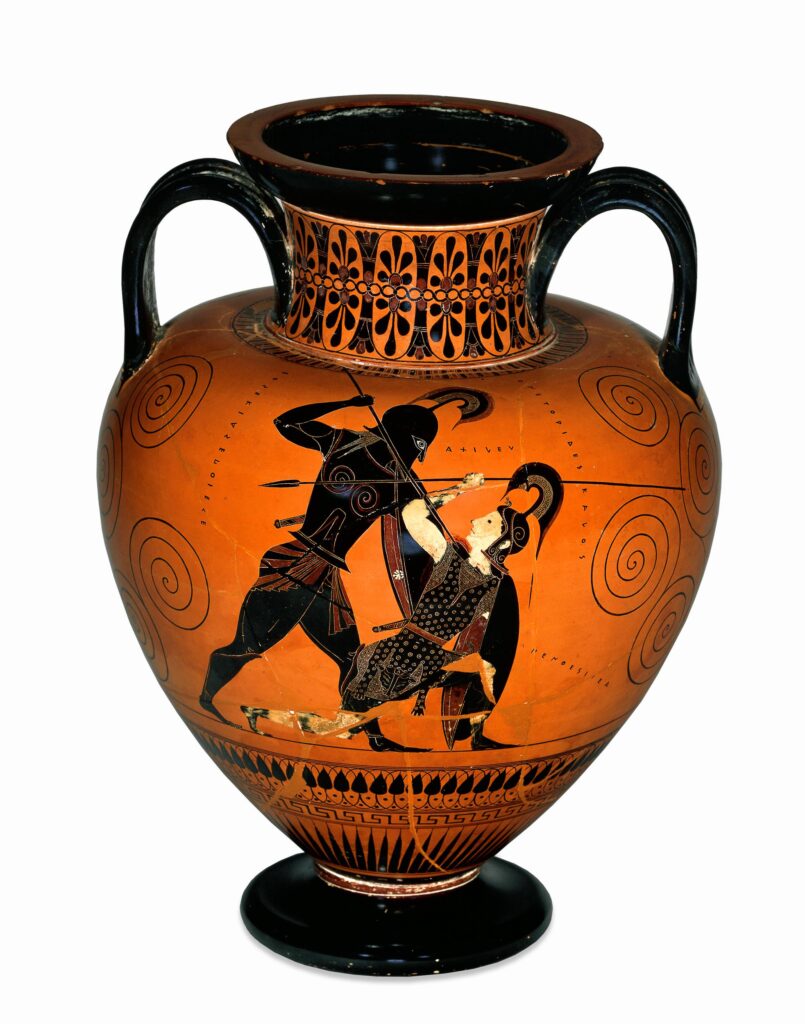

So, that is what Homer has to say about the hero, but there’s still the matter of the “Achilles heel” myth. Early depictions of Achilles’s death in art depict him with an arrow to the torso, not the heel.3 In the third century B.C., Apollonius’s epic poem the Argonautica described the means by which Achilles was made mostly invulnerable. The Argonautica claims that the infant hero was anointed in ambrosia, the food of the gods, and then dunked in fire by Thetis to burn away his mortality. He was held in the flames by the ankle, leaving him mortal, and vulnerable, in that one spot.4

A similar story is recounted later in the Achilleid, an unfinished epic by Roman poet Statius, around 95 C.E.. In this version, it is Thetis dipping baby Achilles in the River Styx in the Underworld, while holding him by his left ankle, which leaves him invulnerable everywhere but there.5 The Achilleid was an attempt to depict the hero’s entire life, but unfortunately, due to Statius’s death, the poem was never finished. Despite this, the partial epic has made a lasting impact. It was very popular; particularly the story of Achilles’s escapades in drag while on the island of Scyros, in an attempt to dodge the draft. Additionally, the idea of the “Achilles’s heel” has persisted and become one of the most well known traits about the hero, to the point where it has gained several new meanings; one anatomical, and one metaphorical.

Death and Romance

Other various endings for Achilles scattered throughout the plethora of Greek and Roman addition’s to his biography include a star-crossed romance. One popular story, which is explored in Ovid’s Metamorphoses as well as Seneca’s Trojan Women, centers around his planned marriage to Polyxena, a daughter of the Trojan King Priam. Achilles agrees to wed the princess to establish a truce between the Trojans and Greeks. Unfortunately for Achilles, the promise of marriage is a trap. Polyxena’s brother Paris hides in the temple of Apollo, where Achilles has planned to meet the princess. The Trojan Prince—in some sources informed of his opponent’s one weakness by his sister, to whom Achilles had entrusted the vulnerable secret—stealthily fires an arrow at Achilles, killing him.67

Another version comes from the Aethiopis, a lost epic composed around the 7th century B.C.E. by an unverified author. Only five lines of the original poem survive, however we are able to piece together the plot through later adaptations. Set immediately after the events of the Iliad, the Aethiopis is the earliest surviving written reference to the Amazon warrior Penthesileia and her relationship to Achilles. The story goes that when the two met on opposite sides of the battlefield, Achilles struck her through the chest with his spear, and at that moment their eyes met. He fell immediately in love, as she died in his arms. After this, Achilles is shot by Paris while attempting to storm the gates of Troy.8

Achilles’ story is a prime example of the way Greek myths were constantly shifting. Even elements that were added long after the “original” source can take on a large importance to the figure. While Achilles may not have started as nearly invincible, with only one weak spot (not literally, at least), the trait assigned centuries after his earliest appearance has become one of the most widely known and beloved parts of his story.

Carrinna Muncy is a third year student at Ohio Wesleyan University, double majoring in zoology and psychology, with a possible minor in classics. She is on the cheer team and is a part of Bishops for Accessibility, and is president of OWU Anime Club. Carrinna has had an interest in Greek mythology since picking up a children’s Greek God’s book in kindergarten, and has researched them ever since. She especially enjoys researching the through lines of myths, and how they change over time.

- Homer, Iliad. Trans. Emily Wilson. ↩︎

- Homer, Odyssey. Trans. Emily Wilson. ↩︎

- British Museum, “Who was Achilles?” ↩︎

- Apollonius of Rhodes, Argonautica. ↩︎

- Publius Papinius Statius, Achilleid. ↩︎

- Ovid, Metamorphoses. ↩︎

- Lucius Annaeus Seneca, Trojan Women ↩︎

- Fragments of Aethiopis. Trans. by H.G. Evelyn-White ↩︎

Images:

Featured image- “Achilles Lamenting the Death of Patroclus” by Gavin Hamilton c. 1760. This work is in the public domain.

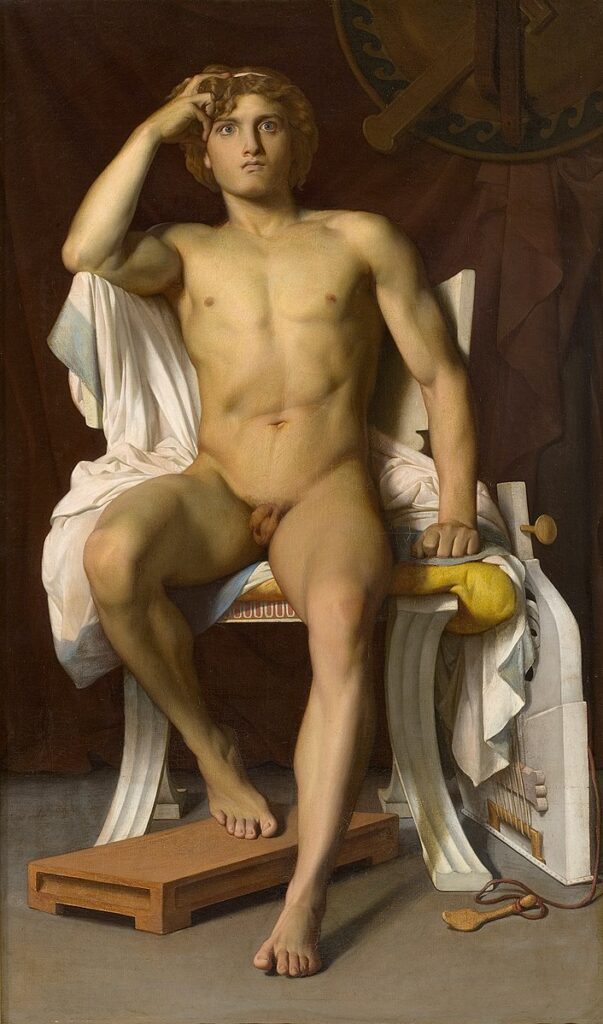

Leon Benouville’s The Wrath of Achilles courtesy of the Fabre Museum. This work is in the public domain.

John Flaxman Jr. sketch courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This work is in the public domain.

Thetis and infant Achilles sculpture courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This work is in the public domain.

Jan de Bray’s The Discovery of Achilles among the Daughters of Lycomedes courtesy of the National Museum in Warsaw. This work is in the public domain.

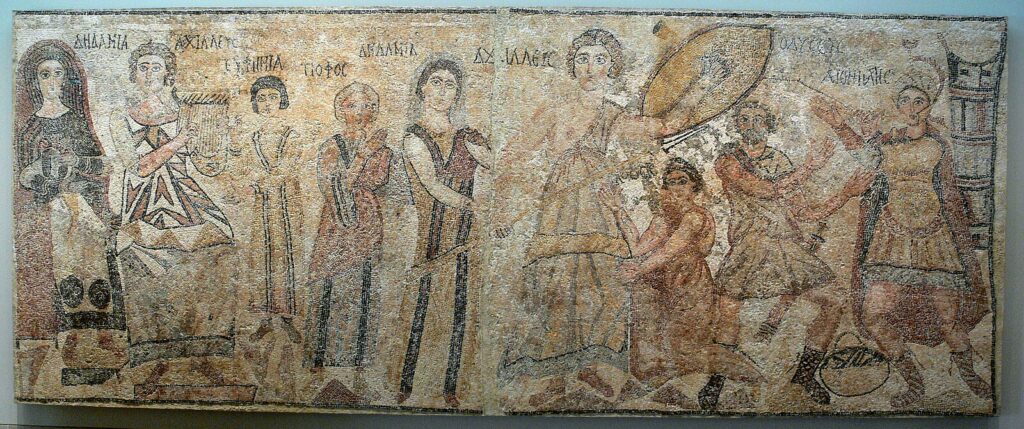

Byzantine mosaic depicting Achilles in the court of Lycomedes courtesy of the Dallas Museum of Art. This work is in the public domain.

Tapestry of Peter Paul Ruben’s The Death of Achilles, woven c. 1630 by Jan Raes. This work is in the public domain.

The Exekias amphora courtesy of the British Museum, this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license.

One thought on “Tracing the Myth of Achilles”

Comments are closed.