What comes to mind when you think of prehistoric civilizations in North America? The Aztec pyramids in Mexico?1 Or maybe the cities carved into stone cliff faces in Colorado?2 While those are stunning examples of pre-modern architecture (in the most literal sense of the term), there is one region of the continent that is often forgotten in popular history, the Midwest.

Even if you grew up in Ohio like myself, it may be surprising to learn that the state has been continuously inhabited for nearly 13,000 years,3 and was once the center of a vast, nation spanning trade network; as well as an epicenter for spiritual and scientific activity. By the time the Roman Empire reached its peak of power an ocean away, Indigenous Ohioans were building vast earth work complexes and creating artwork made from materials sourced from the Rocky Mountains to the Gulf of Mexico to the Atlantic Coast.4 All this around a century before the cliff dwellings in Mesa Verde would be built—not that it’s a competition.

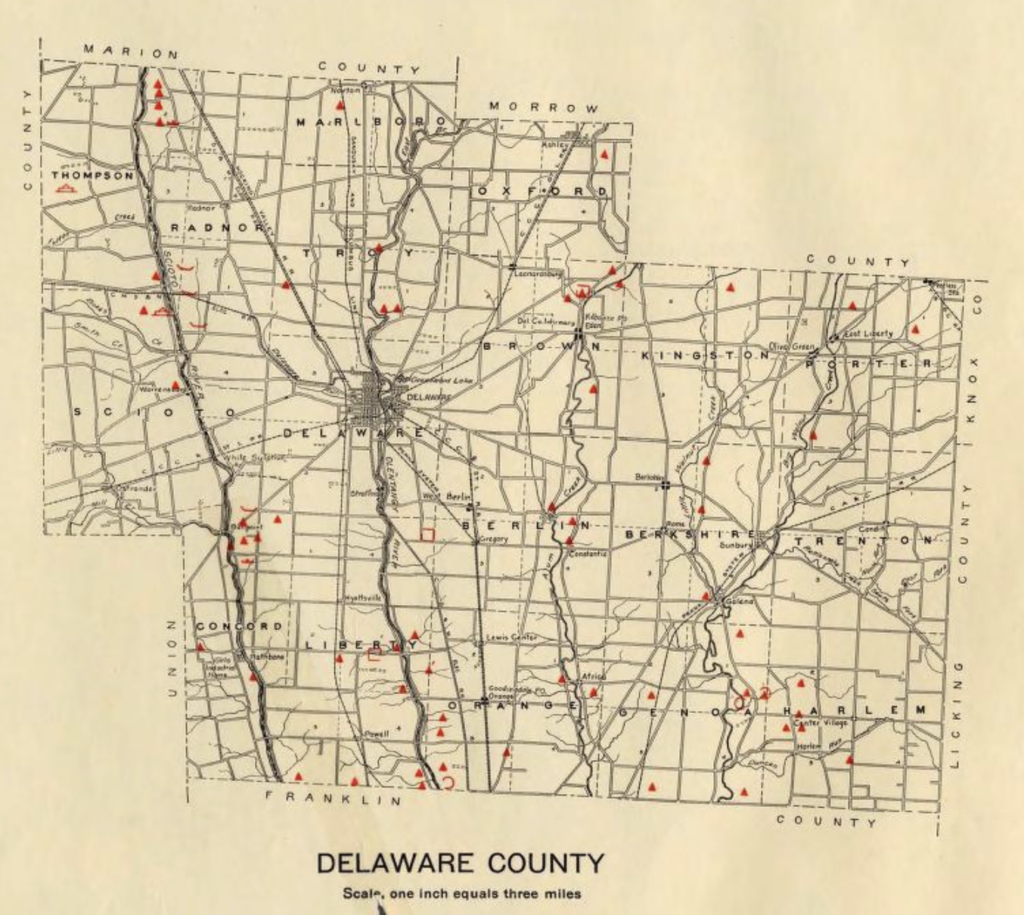

The Hopewell Culture (c. 200 B.C.E—500 C.E.)—named after the Hopewell Farm (owned by Mordecai Hopewell) in Ross County, Ohio where the first mound group was discovered by archeologists—did not, of course, adhere to colonial state borders. They lived throughout what is now Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, and Kentucky, and left a visible mark on the landscape of the Midwest with their architecture. Ross County, Ohio is home to the largest of the Hopewell mounds, which are estimated to have originally measured 500 ft by 180 ft and 30 ft tall (equivalent to about a 3-story building). The entire group, which includes a total of 7 mounds, would have been surrounded by a 35 ft wide wall that enclosed 111 acres of land. This is the largest known single walled earthen enclosure built by the Hopewell Culture.5 Though Ross County holds the superlatives for size, Delaware County had its fair share of earthworks. Unfortunately, most were destroyed by European settlers.6

The architecture isn’t just visually impressive. The geometric construction of the earthworks in Newark, Ohio feature large rectangular structures that align with the 18.6 year long lunar calendar.7 Additionally, the circular earthworks that connect to these rectangular structures are all identical in diameter, even up to 60 miles apart.8 This suggests that the prehistoric Hopewell had a complex understanding of geometry and astronomy, but they haven’t always been credited with such. Brad Lepper of the Ohio History Connection writes about the controversy over the initial discovery of this link:

“Some archeologists have a knee-jerk reaction against archaeoastronomical claims especially when they involve ancient North American societies. This can go beyond legitimate skepticism crossing the border into ethnocentrism or even outright racism. After I got to know [the archeologists who proposed this theory], they told me that when they shared their early work with a senior Ohio archeologist he responded with the confident assertion that the Hopewell could not have aligned their earthworks to the complicated lunar cycle, because those people were savages.”

Brad Lepper writing for Ohiohistory.org, December 2013.

More about the archaeoastronomical history of the Newark Earthworks is currently available at the Ohio History Connection’s “Indigenous Wonders of Our World” exhibit that is now open in Columbus. The exhibit was curated with input from modern American Indian nations that trace their lineage back to the people who built the earthworks.9

The Hopewell weren’t the first or the only culture to create mounds in Ohio. The Adena Culture (c. 500 B.C.E.—100 C.E.) left behind burial mounds all over the state, including one that still stands at Highbanks Metro Park here in Delaware County. The Adena are believed to be responsible for giving Ancient America ideas such as smoking tobacco, creating clay pottery, and possibly even the development of small-scale agriculture.10

So, when did people first decide that Delaware was a good place to make a home, and why? The Middle Archaic Period (6000 BCE-3000 BCE) is believed to be when populations in the state began to increase beyond small bands of hunter-gatherers; as the Earth began to warm and summers lasted longer, the fertile river valley between the Olentangy and Scioto offered everything an ancient society could ask for—think Mesopotamia but in the Midwest. Larger groups began to settle in semi-permanent villages, traveling further north in the summer to mine the copper deposits around the great lakes.11 The earliest evidence found by a team of archaeologists at Cambridge University Press for copper working in the Midwest dates back at least 9500 years, 12 making metal working in America contemporaneous with its emergence in the Middle East.13

Similar to the reaction to the Hopewell people’s in depth knowledge of mathematics and astronomy, discussions surrounding metal working in prehistoric America tend to be dismissive of the ancient peoples’ abilities. For a long time, the fact that ancient Americans never developed wide scale production of metals such as bronze and steel was used to justify beliefs that they were less developed than metal working cultures in Europe. However, archaeologist Michelle Bebber of Kent State University has recreated various copper tools and weapons created by these Archaic cultures, and she came to a very different conclusion as to why copper working never evolved into a Bronze or Iron Age.14 In her experiments, bone and stone tools performed just as well as copper, and were far easier and quicker to make. Bebber writes that the cultures making these tools were “highly innovative,” and would “regularly experiment with novel materials,” so it would make sense for them to move on if copper just wasn’t worth the trouble.

Temperatures generally continued to rise in the Late Archaic (3000 BCE-1000 BCE), and settlements became more permanent. Staying in one place for longer stretches freed up time for these early Ohioans to focus on art, agriculture, and trade. The northern settlements continued to mine and work copper to produce tools, jewelry, and weapons that were traded “on an almost industrial scale,” according to archaeologists E.J Neiburger and Sarah Shulman writing for the Central States Archaeological Journal.

It was out of these Archaic Copper Working Cultures that the Adena, Hopewell, and other Woodland Cultures (1000 BCE-100 CE) would evolve. The introduction of pottery was a major game changer, allowing people to store and transport large quantities of food. Agriculture began to become a major source of sustenance, and evidence of complex ritual activity and social stratification began to appear in the archaeological record.15

Like so many great civilizations, the prehistoric cultures of Ohio disappear from the record quite suddenly. There was not one thing that could have destroyed such a massive civilization, and historians and archaeologists believe that a combination of cooling climates, increased warfare, and natural disasters all contributed to the fall of the Woodland Civilizations. Despite this, many holdovers from these ancient cultures were carried into later civilizations, with some groups continuing to inter their dead alongside those laid to rest in centuries old mounds up until 1000 C.E..16

- Heidi King, “Tenochtitlan: Templo Mayor: Essay: The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History,” The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, January 1, 1AD, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/teno_2/hd_teno_2.htm. ↩︎

- “Cliff Dwellings.” National Parks Service. https://www.nps.gov/meve/learn/historyculture/cliff_dwellings_home.htm.

↩︎ - “Prehistoric Inhabitants: Encyclopedia of Cleveland History: Case Western Reserve University.” Encyclopedia of Cleveland History | Case Western Reserve University, June 18, 2018. https://case.edu/ech/articles/p/prehistoric-inhabitants.

↩︎ - “Hopewell Culture.” Encyclopedia Britannica, July 20, 1998. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Hopewell-culture.

↩︎ - “Hopewell Mound Group.” National Parks Service, July 18, 2023. https://www.nps.gov/hocu/learn/historyculture/hopewell-mound-group.htm.

↩︎ - Mills, William C. “Delware County .” Essay. In Archeological Atlas of Ohio: Showing the Distribution of the Various Classes of Prehistoric Remains in the State, with a Map of the Principal Indian Trails and Towns, 21–22. Columbus: For the Society by F.J. Heer, 1914.

↩︎ - Lepper, Brad. “The Archaeoastronomy of the Newark Earthworks.” Ohio History Connection, March 14, 2022. https://www.ohiohistory.org/the-archaeoastronomy-of-the-newark-earthworks/.

↩︎ - Ruby, Bret J. “Hopeton Earthworks to Be Nominated to the World Heritage List (U.S. National Park Service).” National Parks Service, March 24, 2021. https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/hopeton-earthworks-to-be-nominated-to-the-world-heritage-list.htm.

↩︎ - “Indigenous Wonders of Our World – The Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks.” Ohio History Connection, April 27, 2022. https://www.ohiohistory.org/visit/ohio-history-center/current-exhibits/indigenous-wonders-of-our-world/.

↩︎ - Abrams, Elliot M. and Ann Corinne Freter. Emergence Of Moundbuilders: Archaeology Of Tribal Societies In Southeastern Ohio. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2005. ↩︎

- Neiburger, E.J., and Sarah Shulman. “Collapse of Prehistoric Midwest Civilizations.” Central States Archaeological Journal 64, no. 1 (2017): 36–41. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44159825. ↩︎

- Pompeani, David P, Byron A Steinman, Mark B Abbott, Katherine M Pompeani, William Reardon, Seth DePasqual, and Robin H Mueller. 2021. “On the Timing of the Old Copper Complex in North America: A Comparison of Radio Carbon Dates from Different Archaeological Contexts.” Radiocarbon 63 (2). Cambridge University Press: 513–31. doi:10.1017/RDC.2021.7. ↩︎

- Malakoff, David. “Ancient Native Americans Were among the World’s First Coppersmiths – AAAS.” Science.org, March 19, 2021. https://www.science.org/content/article/ancient-native-americans-were-among-world-s-first-coppersmiths.

↩︎ - Bebber, Michelle. “The Role of Tool Function in the Decline of North America’s Old Copper Culture (6000-3000 BP): An evolutionary and experimental approach.” Doctoral dissertation, Kent State University, 2019. http://rave.ohiolink.edu/etdc/view?acc_num=kent1562332469526957 ↩︎

- Ibid, Neiburger and Shulman. ↩︎

- Redmond, Brian G. “Intrusive Mound, Western Basin, and The Jack’s Reef Horizon: Reconsidering the Late Woodland Archaelogy of Ohio.” Archaeology of Eastern North America 41 (2013): 113–44. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43868947. ↩︎

Images

Featured image by Mike Sharp, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike International 4.0, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/

Serpent effigy image by Daderot, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike International 4.0, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/

Render of Newark Earthworks courtesy of The Ancient Ohio Trail

Adena pipe image by Tim Evanson, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic Licence, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/deed.en

Cahokia copper plate image by John P. Rogan, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike International 4.0, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/

Woodland pottery image by Deborah Platt, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic Licence, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/deed.en