by Helena von Sadovsky

Many popular images of hell burst with fire and torture, demons and brimstone, and modern novels, music, and television offer many opinions on what hell could look like. A recent interpretation of hell in the television show Good Omens, based on Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman’s cult classic novel of the same name, is a bureaucratic and impersonal hellscape of dark halls, dripping ceilings, and endless lines. But medieval depictions of hell and its damned may be downright surprising to us today. Both Italian poet Dante Alighieri and the “father of English literature,” Geoffrey Chaucer, compose literary judgements upon the dead, including heroes of classical myths known as the aristos achaion, the “best of the Greeks.”

Crime and punishment are central themes in Dante’s literary exploration of hell in his Inferno, the first of three books in his Divine Comedy, a narrative poem from the early 14th century. But who is punished, and for what, is just as interesting as his conception of the structure of hell itself. While Dante places many contemporary and past historical figures in the various levels of hell, he also includes a multitude of characters drawn from classical myths. These mythic heroes and villains serve a unique role. They mark both Dante and his audience as learned in the classics while also serving to judge the “classical” values that Dante considers to be archaic and unchristian. Similarly, Chaucer utilizes Classical myths and motifs extensively in his poem Parliament of Fowls. In both cases they provide a point of reference for the educated, courtly, medieval audiences of these works.

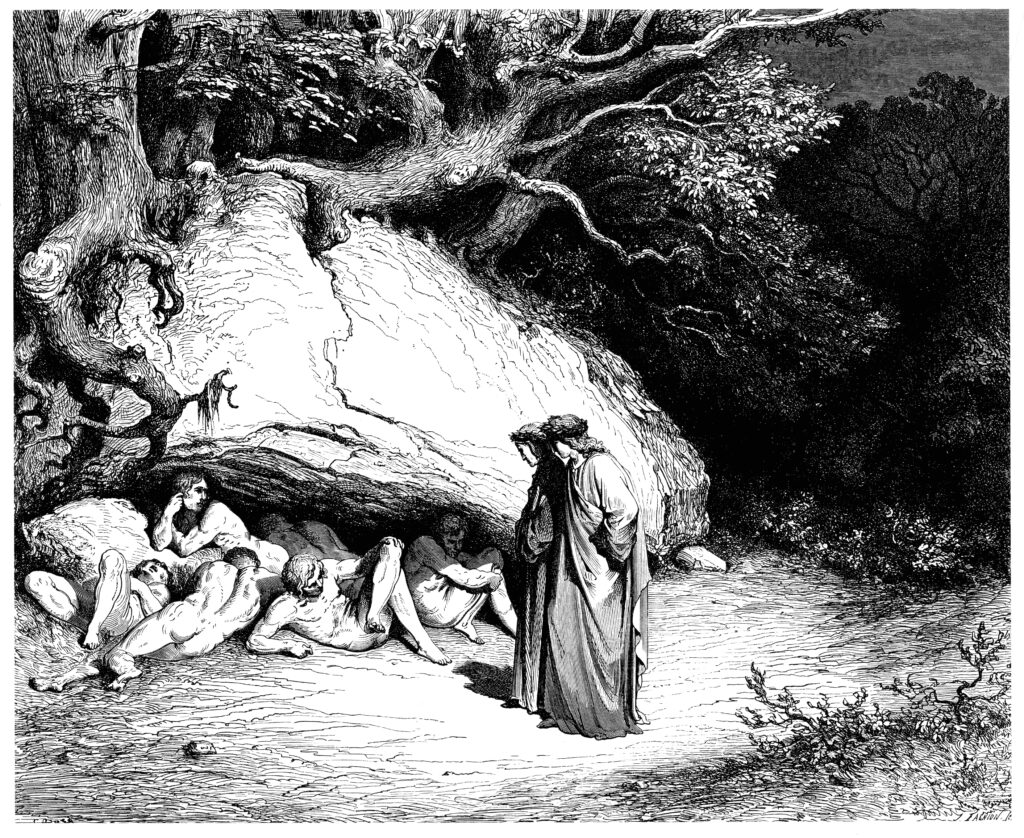

The Virtuous Pagans

The first classical figure the audience encounters in the Inferno is a real person. The ancient Roman author of the Aeneid, Virgil, is Dante’s favorite poet, and he serves as a guide for both the Dante pilgrim and the reader. He not only protects Dante through his woeful adventures but also offers wisdom for how to remain on the path to salvation. What makes Virgil’s advice particularly poignant is the fact that he himself, as a pagan, cannot follow it. Although he is not being tortured by demons or by frozen tears, he is still being tormented by the fact that he will never “know” God. He says as much to Dante, explaining the fate of those in Circle One:

“…[T]hese never sinned. And some attained to merit.

But merit falls far short. None was baptized.

None passed the gate, in your belief, to faith.

They lived before the Christian age began.

They paid no reverence, as was due to God.

And in this number I myself am one.

For such deficiencies, no other crime,

we all are lost yet only suffer harm

through living in desire, but hopelessly.” (Dante, Inferno 4.34-42)

It seems harsh that those who were good people yet not aware of Christianity should suffer for all eternity in such a way. Anticipating his audience’s reaction, the Dante pilgrim appears to agree with this; he states that, “at hearing this, great sorrow gripped my heart” (4.43). However, Virgil, answering Dante’s question about the possibilities of redemption, appears to be satisfied with the arrangement. He says, “‘All these [Old Testament heroes] He blessed. / This too I mean you’ll know: until these were, / no human soul had ever been redeemed’” (4.61-63). Dante uses Virgil to rationalize the punishment, effectively saying that “it’s okay because humanity was saved.” While creating some interesting plot holes by not actually answering the resulting questions (such as: are there truly no exceptions for the ignorant, and what power do God and Jesus have over hell?) this exchange demonstrates Virgil’s ability to reason. His noble and self-sacrificing reasoning demonstrate his borderline holiness and explains why he was chosen to guide Dante. It also suggests that the damned are capable of understanding their own culpability, making those who remain ignorant of their sins all the more at fault.

Elektra: Betrayal or Justice?

While it is easy to understand why Virgil deserves this comfortable spot in hell, Dante’s qualifications appear to be less strict for others. For example, one of the people Dante sees in the First Circle is Elektra. The daughter of Agamemnon, Elektra is renowned for helping her brother Orestes murder their mother in revenge for the death of their father. However, their mother, Clytemnestra, murdered her husband for sacrificing their daughter Iphigenia and her desire to keep her affair and the throne (Shamberg). Their story begins with filicide and ends with a mariticide and a matricide, staining the entire family’s hands with blood. Why then does Elektra not reside in the Ninth Circle with the other traitors to family?

One possible explanation is that Elektra was committing an act of vengeance. Throughout the Divine Comedy, acts of violent moral righteousness, even wrath, are seen as good if committed within the grace of God. This is established by Virgil himself in Canto 8 when he responds to Dante’s harsh rebuke of a sinner and his desire to see him torn to shreds by saying, “’You wrathful soul! / Blessed the one that held you in her womb[…] And rightly you rejoice in this desire’” (8.44-45, 57). However, was Agamemnon worth avenging? Such a notable figure would surely have been mentioned among the heroes in Dante’s First Circle. But he is notably absent. Perhaps then it was Elektra’s love for her father (honoring her parent) that bought her a (slightly nicer) spot in hell.

Lovers’ Destruction

The First Circle is not the only place where Dante intersperses classical heroes. In the Second Circle there are those “here condemned for carnal sin” (5.38). They are doomed to spend an eternity in swirling winds which whip them about, painfully, causing them to curse God. Some figures, such as Semiramis, were well known for their incest; others, like Tristan, are figures from courtly romances. Helen and Paris are in this circle—their lust for one another lead to many deaths.

Dante puts Achilles in this circle, whom Virgil says “fought with love until his final day” (5.66). But who is this “love” referring to? An ancient or modern audience might assume this reference to his final day suggests Patroclus. Whether the two had any sort of romantic relationship is a common debate. However, if Dante were to insinuate a sexual relationship between the two, it is more likely that he would have placed him in Circle Three with other “sodomites.”

We must also consider how unlikely it was that either Dante or Chaucer would have read Homer’s original Greek Iliad in which a sexual relationship between Achilles and Patroclus was explored. Instead, Dante would have been familiar with the epic poem Le Roman de Troie, written by the mid-12th century poet Benoit de Sainte-Maure. Le Roman de Troie and its subsequent medieval retellings center Achilles’ romantic narrative around a female lover, Polyxena, in order to explore courtly love. According to Dictys of Crete’s account of the Trojan War, translated from the Greek and available to medieval Romance authors such as Benoit de Sainte-Maure, Polyxena was a daughter of Hecuba and King Priam of Troy (Cretensis).

Achilles’ eternal punishment in a storm seems to be based on his loss of reason, for “the passion of love destroys him in the Troie” (Thompson). The passion in question connects perhaps to his inordinate vengeance of Patroclus’ death, but it is at least connected to Polyxena:

“He saw Polixena there, a clear view of her face. This is the occasion and the means by which he will be snatched from life and his soul parted from his body. Hear what destiny did! Now you will hear how he was totally destroyed by fine amor.” (Thompson, translation of Le Roman de Troie)

But even medieval audiences had to recognize the bond, brotherly or otherwise, between Achilles and Patroclus. His love for Patroclus drove him to despair. In the Iliad, Homer states that, after Patroclus’ death, “Achilles chose to build an immense mound for Patroclus and himself” (lines 146 -147). This suggests that Achilles plans on being buried with Patroclus rather than surviving the war. This theory is further reinforced by Achilles’ anguished prayer to Spercheus:

“All in vain my father Peleus vowed to you that there, once I had journeyed home to my own dear fatherland, I’d cut this lock for you and offer splendid victims, dedicate fifty young ungelded rams to your springs, there at the spot where your grove and smoking altar stand! So the old king vowed—but you’ve destroyed his hopes. Now, since I shall not return to my fatherland, I’d give my friend this lock… and let the hero Patroclus bear it on his way.” (Homer, lines 165-174)

Directly following this, Achilles marches to battle and his death. Not only did he despair and essentially decide to kill himself, but he also abandoned his duties to his family. As a prince, he was meant to return home and eventually lead his kingdom. His love for Patroclus may have driven him to lose all regard for any of his earthly responsibilities.

Additionally, as a pagan, he was neglecting his spiritual responsibilities. Altogether, he was arguably committing multiple deadly sins: wrath, pride, and despair. However, Dante places him in the Second Circle because love drove him to commit these sins. As such, he is doomed to spend an eternity in a storm, in pain, with only the memories of his love and happiness to keep him company. And as Francesca says, “'[t]here is no sorrow greater / than, in times of misery, to hold at heart / the memory of happiness” (Dante, 5.121-123).

Chaucer on Heroic Lovers

Chaucer also chooses to focus on Achilles’ love. In his work The Parliament of Fowls, he mentions Achilles alongside Semiramis, Candace, Hercules, Byblis, Dido, Thisbe, Piramus, Tristan, Isolde, and many others that Dante placed in his Second Circle. Of these he writes that, “Alle these were peynted on that other syde, / And al hir love, and in what plyte they dyde” (Chaucer, lines 293-294). It is interesting that Chaucer refers to love as a plight in this instance. While it makes sense given the tragic nature of these characters, it is different from his treatment of love in other portions of the story. This passage is rather Dante-esque: love has driven these figures to destruction. However, there are other instances where he glorifies love and accepts it fully. Chaucer uses the word “noble” and the personifications of Peace and Patience in his story to describe his heavenly locus amoenus, the “place of delight.” He illustrates the positives and negatives of love in the same location. Finally, he never names Patroclus as the focus of Achilles’ affections.

Additionally, unlike Dante, Chaucer includes Hercules in his list of lovers driven to destruction. Hercules, under the influence of Hera, murdered his wife and children in a rage. But Dante places Hercules in the garden of good pagans alongside Virgil. While Hercules did commit great deeds, he also had many sins. Perhaps Dante thought that because Hercules’ misdeeds regarding his family were caused by the wrath of a pagan deity, he should be forgiven. Servius, when interpreting the Aeneid, came to the conclusion that Hercules’ destruction of Cerberus could be read through a Christian lens: “Inasmuch as Cerberus is really earth, the consumer of bodies, Charon’s remark that Hercules chained the animal and dragged him trembling from the underworld is a figurative way of saying that the hero contemned and subdued all earthly lusts and vices” (Jones 221). It stands to reason that Dante would have been familiar with Servius’ interpretations, and this likely informed his placement of the great hero in the First Circle.

Overall, Chaucer and Dante’s placement of classical characters in hell and heaven provides insight into how medieval peoples interpreted classical mythology through a Christian lens. Both Dante and Chaucer utilized Classical figures as a means of reaching their respective audiences, which would have been well versed in the Greco-Roman myths. But whether they condemn or forgive the “best of the Greeks,” both poets conclude tragically that their pagan religion keeps them from the highest reaches of heaven.

Helena von Sadovsky is a junior at Ohio Wesleyan University majoring in Medieval Studies with a minor in Art History. She has a passion for medieval armor and leaves no image nor allusion unturned when dissecting medieval literature. On any given day she can be found wandering campus with a hand and a half practice sword.

Works Cited

Chaucer, Geoffrey, and Kathryn L. Lynch. Dream Visions and Other Poems. W.W. Norton, 2007.

Cretensis, Dictys, and R. M. Frazer. “Dictys Cretensis Book 3.” Theoi Classical Texts Library, Theoi Project.

Dante, Alighieri, and Robin Kirkpatrick. Dante, the Divine Comedy. Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Homer and Robert Fagles. The Illiad. Penguin Classics. 1998.

Jones, J W. “Allegorical Interpretation in Servius.” The Classical Journal, vol. 56, no. 5, Feb. 1961, pp. 217–226.

Shamberg, Caitlin. “Who Was Elektra?” Getty Iris, Getty Museum, 2 Nov. 2020, https://blogs.getty.edu/iris/who-was-elektra/.

Thompson, Diane. “Love Destroys Achillès in Benoit de Sainte Maure’s Roman de Troie.” Troy, Northern Virginia Community College. Adapted from: “Human Responsibility and the Fall of Troy,” Diane P. Thompson, DIS., CUNY, 1981.

Cover image: The Barque of Dante. Eugène Delacroix. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

a Plate XI: Canto IV: The Virtuous pagans. Gustave Doré, ca. 1832 – 1883. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

b Electra at the Tomb of Agamemnon. Frederic Leighton. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

c Published by Guillaume Rouille(1518?-1589), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

d Battle Around the Body of Patroclus. Anonymous, School of Fontainebleau, ca. 1543–ca. 1547. Open access public domain, Metropolital Museam of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/699520.

e Marble statue of a bearded Hercules. 68–98 CE. Open access public domain, Metropolital Museam of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/247001.