Last we left off, the state of the kingdom of the Franks was an unsteady one, as the balance of power had suddenly shifted with the death of Sigibert and Chilperic. In short order, their wives were in charge of their kingdoms as regents for their sons. Brunhilde and her son Childebert II waxed in power, seizing much of the lands once belonging to Chilperic and putting his wife and son on the knife’s edge. Considering the political history between these royal factions, it seemed unlikely that anything could stop the violence. It was at that point that Guntram made himself known.

Guntram had been quietly governing his own kingdom of Burgundy ever since he inherited it in 561, occasionally getting involved in the disputes of his brothers and their wives in order to secure gains for himself. He would wage war for both the Austrasians and the Neustrians. Twenty years on, he was well established and powerful, and was looking forward to using his seniority in the royal dynasty to secure even greater authority. As the royal uncle, he could serve as a mediator for the feuding cousins and their mothers, and bolster his own prestige in the eyes of the nobility.

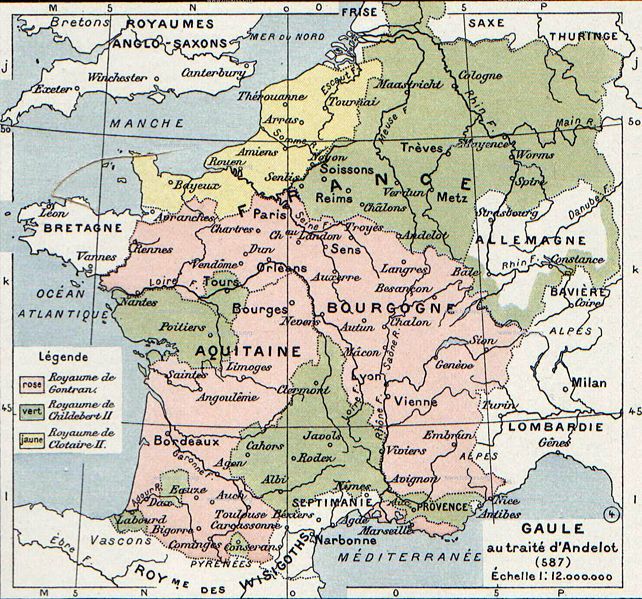

Guntram also could dangle the prospect of inheritance over his nephews; he had no living sons, having killed his eldest and losing his younger son to illness. According to Gregory of Tours, the first was at the instigation of his new wife, and the second was God’s punishment for the sin of filicide. Already he had negotiated with Childebert and Brunhilde in the treaty of Andernach, gaining territorial concessions in return for an alliance and for naming Childebert as his heir. In addition, he chose to stand as godfather to Fredegund’s son Chlothar II, which gave him a position of superiority over Chlothar’s court. He assembled the nobles of Neustria, the kingdom Chilperic held, and before them confirmed the legitimacy of Chlothar II as his father’s true son and heir and assisted his elevation, as well as that of his mother. In addition, he refused to turn over the boy king and his mother to the power of Childebert and Brunhilde. In doing so, he confirmed their power while also keeping much of it to himself. As long as Guntram reigned, he would ensure that neither faction could destroy the other, and he would remain the hegemon of the Merovingian dynasty.

Guntram needed the aid of his nephews, as he himself was facing a great threat from the south. Gundoald, a Frank claiming to be Guntram’s brother and therefore a legitimate heir, had invaded, receiving support from several dukes and counts of Guntram, as well as former retainers of Chilperic. Much of southern Gaul fell to his control, and it would take over a year for Guntram to crush the revolt. During this time, Chlothar’s generals, under orders from Fredegund, captured back several cities in the north that Childebert had taken from them, bolstering the position of Chlothar and evening the balance of power between the younger kings.

This power grab was seen as unacceptable to Guntram, and once he had defeated and killed Gundoald he came north and put Fredegund under house arrest, making himself regent for Chlothar and effectively annexing his kingdom. Eventually Guntram was back in the south of Gaul, this time to fight the Visigoths in Spain when Fredegund managed to escape and reassert herself as regent for her son. Guntram returned again with force but this time was unable to dislodge her. This, for him, was the final straw. Fredegund clearly was not willing to become his subordinate, and so he solidified an alliance with Childebert, and the two kings, supported by Brunhilde, pursued the total destruction of Fredegund and her son.

Unfortunately for Brunhilde and Childebert, the already aged Guntram would die in 592, before they could destroy the Neustrians. Fortunately for them, his death meant that Childebert could, in accordance with the treaty, claim his kingdom as well. Childebert was now very close to becoming the supreme king of the Franks, and set his sights upon Chlothar’s reduced kingdom. Unfortunately for him, he would not live to see his cousin destroyed, as in either 595 or 596 he and his wife died in short order from illness. Many at court, however, suspected foul play. Certainly, Chlothar and Fredegund may have been responsible, but some went as far as to claim that the king’s mother, Brunhilde was responsible. She had held power for a long time as regent for her son, and now that he had become an adult and had married a wife of his own, it seemed as if he was becoming distant from his mother’s influence. According to the anonymous author of the Chronicle of Fredegar, our new source for these later years of the 6th and early 7th centuries, this may have been the case (although the Chronicle suffers from an inverse bias to Gregory of Tours; it is very sympathetic to Chlothar II and Fredegund, and casts Brunhilde as an evil tyrant queen, so many of its claims are likely exaggerated or downright untrue).

Regardless of what the cause was, Childebert’s death meant his lands were now entrusted to his two young sons, Theudebert II and Theuderic II. The former received his father’s kingdom of Austrasia while the latter was given Burgundy, the kingdom of Guntram. Brunhilde established herself as regent for Theudebert and initially remained in his court. Fredegund tried to take advantage of the situation by sending an army to invade after the old king’s death, but saw only limited success. The next two years saw a stalemate on the frontier between Chlothar’s realm and that of Brunhilde’s grandsons, until in late 597, suffering from illness and old age, Fredegund would soon perish.

Her death must have been a joy for Brunhilde to hear. Not only had she outlived her sister’s killer, but his evil wife who instigated the deed was gone too! Now all that remained was to destroy their son, and her line would be secure as rulers of the Franks. Unfortunately for Brunhilde, her grandsons proved more unruly than she may have thought they’d be. Although she would outlive Fredegund by more than a decade, it would be Fredegund’s family line who would have the last laugh, and Brunhilde would eventually be undone.

Chlothar now ruled alone, though by this point he was now old enough to be considered a man by Frankish custom, and was thus able to begin ruling his own kingdom, with the aid of some advisors loyal to his mother and father. His court was small, and he only held about an eighth of the kingdom, but he was still firmly established, and Brunhilde knew it would take a concerted effort to dislodge him and his loyal supporters. Her grandsons were not up to the task. The two of them felt secure in their positions and saw Chlothar as no threat, and were thus more concerned with each other. They defeated Chlothar in battle around 600 and reduced his domains even more, but did not go further, as they fell into conflict with one another.

Brunhilde also began to face different opponents in the royal court in Austrasia. Several nobles encouraged Theudebert II to turn against his mother, and he increasingly resisted her advice and began to favor other counselors, until in 599 he asked her to leave his court at the urging of his young aristocratic followers, who chafed at the influence this foreign queen held. Brunhilde made her way to the court of her other grandson, Theuderic, and began to despise Theudebert for dismissing her, so much so that the next twelve years her attention turned from Chlothar, and towards the affairs of her grandsons and the royal court in Burgundy.

Brunhilde was increasingly ruthless in her governance, and where she once had been a more passive and conciliatory figure at court, she now began to dominate politics by eliminating rivals at court and appointing her own followers to high government offices. One of her targets was Berthoald, was the mayor of the palace, who was essentially the head of the royal court. For that reason alone he was an obstacle to power, and so Brunhilde, with the support of the young noble Protadius (who was rumoured to be her lover), plotted his demise. Berthoald was sent to inspect estates near the border of Chlothar’s kingdom, at which point Chlothar sent Landric, his own mayor, to attack and kill him. This plot allowed Protadius to become the new mayor of the palace in Burgundy, which allowed Brunhilde to exert great influence on the king.

In order to expand her own power, Brunhilde had to expand the powers of her grandson, Theuderic. To that end she began to encourage him to feud with his brother Theudebert, reminding her grandson how he had dishonored her by exiling him from her court, and by promising that by defeating him Theuderic could rise to become king of all the Franks. Eventually, the king agreed, and Protadius was made to accompany him in leading an army against Theudebert. The nobles, however, did not want to undertake such a bloody campaign, and rebelled against the king by targeting his advisor. While Protadius was playing dice in his army tent, a group of soldiers seized him, as well as the king. Theuderic gave orders to his officer, duke Uncelen, to have Protadius released. Uncelen, however, went to Protadius’ tent and claimed that the king ordered Protadius dead. After the deed was done, the campaign was called off, and a furious Brunhilde soon sent her followers to hunt down and murder Uncelen.

Brunhilde was desperate to see Theudebert destroyed, and so she took drastic action. Brunhilde prompted Theuderic to seek an alliance with Chlothar, going so far as to ask him to stand as godfather to Theuderic’s newborn son, Merovech. This pact was made so that the two kings could destroy the Austrasians, at which point Theuderic would be strong enough to kill Chlothar II and reunite all the Frankish Kingdoms. The alliance invaded Theudebert II’s realm, and from 610 to 612, several massive battles saw the brothers fiercely battle for control, while Chlothar aided mainly by reclaiming lands for himself in northern Gaul. Eventually, Theudebert was captured and killed by Theuderic, who was then directed by his grandmother to pursue one final war, this time against Chlothar, to finish the job. Victory seemed so close for Brunhilde, until fate struck yet again, and Theuderic II died of dysentery in late 612.

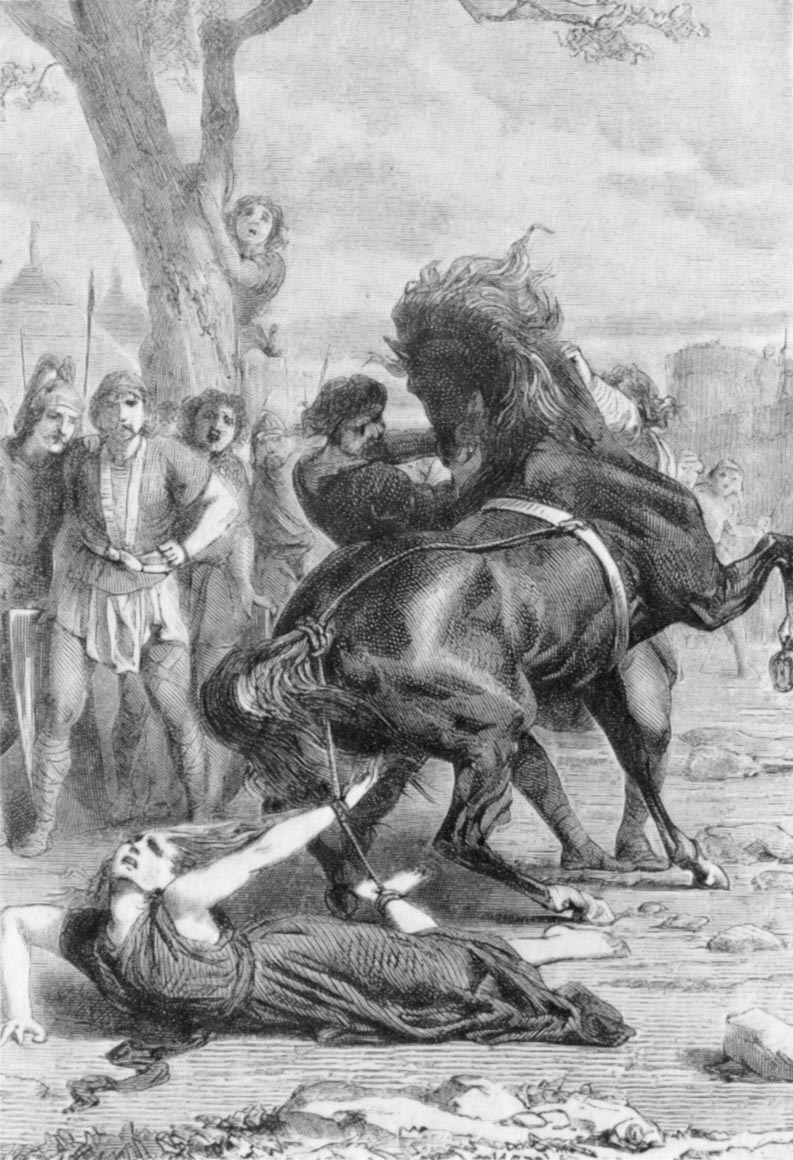

Brunhilde scrambled to put her great-grandson, Sigibert II, on the throne, but it was already too late. Her assassinations and influence on previous kings had angered a faction of the nobility, who sought to undo her. This was done by means of a secret plot, with the Warnachar, mayor of the palace of Austrasia, and Rado, mayor in Burgundy, conspiring with Chlothar II to destroy Brunhilde and her new boy king. Feigning support for her, they arrived with their regiments for battle against an army of Chlothar, followed by switching sides before the battle could begin. Brunhilde attempted to flee, but was captured along with the young king. Chlothar had his aunt executed by having her tied to a horse, which was sent running through the streets, and murdered the young Sigibert II as well, although he spared Merovech as he was his godfather. Weird, how that was where he drew the line.

With Brunhilde and Sigibert’s deaths, Chlothar II became undisputed ruler of the Franks, and held power until his death in 629. His descendants would rule the Franks for the remainder of the history of the Merovingian dynasty. Although her son would win, Fredegund did not get to witness it, and Brunhilde held great power just before her fall. The most important thing about this story isn’t the rivalry, but the fact that these two women, one a foreigner and the other a lower-class mistress, both managed to gain and hold power in their own right, garnering respect from peers and managing to effectively hold power and use it for their own ends. While there is no denying that their feud was a defining aspect of their lives, they also were patrons of art and religion, and both were virtuous (and powerful) enough to receive praise from both contemporaries and later writers. Too often is the history of women ignored, but the story of Brunhilde and Fredegund is an example of how women could and did operate with agency in the early Medieval world, and managed to change history as a result.