This review was written by Dr. Donald Lateiner, Professor Emeritus of at Ohio Wesleyan University Humanities-Classics & AMRS departments, regarding a book recently published by Dr. Deborah Kamen discussing insults and derogatory language among the Ancient Greeks. We would like to thank Dr. Lateiner for contributing this article, and for being willing to work with the OWU Trident.

Kamen introduces her understudied, dark corner of Athenian social and anti-social history with a flourish. She assembles contemporary cross-cultural anthropological and sociological approaches to insults before addressing ancient Attic comments and acts that denigrate others. Such discourse helps negotiate status, especially in an agonistic society—one in which competitive values are displayed more obviously than cooperative ones. The five chapters that follow treat the creative varieties of doing down others—intimidating equals, inferiors, and superiors—in classical Athens, chosen for its rich evidence. Kamen discusses the regulation of insults, especially the extreme level—hubris. Public and private, informal and legal means of preserving honor and blocking or redressing objectionable behaviors receive due attention.

Her five chapters advance from playful banter, “benign insults,” to more seriously offensive active and passive forms of one-upmanship and literal smack-downs. First come three categories of socially acceptable “benign insults:” nasty comments, then mockery in comedy, third, abuse and railery. She then turns to forbidden insults, that is, hurtful words that could be litigated. Kamen’s fourth category of slander and libel, anticipates hubris of the legal kind—not tragic aggressive pride but verbal assault and physical battery. The law here poses conceptual pitfalls, knots of intentionality and attitude. The Athenians meant harm for which you could not apologize.

One has no scale now to measure the degree of humiliation involved in the “pervasiveness of mockery in many different Greek rituals” (28). Mockery (chapter 1) featured prominently at Demeter festivals. Rituals included visual obscenities, originating according to myth in the miserable goddess Demeter’s sidekick Iambê’s playful joshing. Humans too suffered “hazing” (22) in Eleusinian initiation, a series of verbal and ritual events into an Athens-based Mystery cult promising a joyful afterlife.. “Playful whipping” (24) seems a more problematic category of festive mockery. Carnivalesque social reversals may explain some vigorous vigorous venting of insults in Dionysiac phallic processions. The fun of the symposium or drinking party, when not Platonic, included barbed remarks, gestures, and rejoinders, Some scholars discern unwritten limits (cf. 31 discussing Aristophanes’ Wasps 1222-49). Kamen thinks insults at these parties “could aid in the cohesion of the group’s members through laughter,” but offers no examples.

Kamen’s rosy view of Spartan “benign insults” misunderstands Plutarch’s fantastic and anachronist report about their their severe rules for “preventing light hearted mockery from turning abusive” (33, Plutarch, Life of Lycurgusurgus 12.4). That harsh but poorly documented society offered no mercy to chosen victims of humiliation, whether cadet cadet citizens, full Spartiates, or the defenseless serf-like class of helots. As we all know, shaming insults often cross the invisible line from witty jest to permanent hurt for the victim’s self-esteem or public status.

Chapter 2 surveys mockery in Attic Old Comedy, the parameters of insults against public and private persons tolerated in a specific public, state-sponsored venue. One cannot determine their “relative harmlessness” (37) when cast chiefly at people of “wealth, high birth, and influence” (see Pseudo-Xenophon Government of the Athenians 2.18). She doubts any ban ever passed prohibiting making fun of politicians by name. They are mocked for foreign birth, especially when it was barbarian, low origins (servile), and menial occupations, cowardice in battle, sexual or gender deviance such as multiple available receptor orifices), animality, abuse of parents, and decrepit old age. Kamen could have added to these forms of character assassinations excessive wine-consumption.

Chapter 3 focuses on invective in Attic oratory, and how court briefs progressed from the self-imposed courtesy of the fifth-century orators to the coarse genealogical and sexual gibes uttered in the later fourth century. In Demosthenes, for example, the sexual escapades for pay performed by a competitor’s mother took place in an outhouse next to a hero’s shrine. “The right to denigrate” faced few Athenian law-court limits—a theatrical branch of government. Humorous gibes gained bored citizen-jurors’ grateful goodwill. Such invective both diminished one’s opponent’s standing, boosted a speaker’s credibility, and aligned him with community morals (85).

Chapter 4 advances from permitted insults (religious and convivial, stage, and court) into taboo verbal abuse, statements actionable at law by a variety of private law-suits. One could not say a man was a ‘killer,’ a father- or mother-beater, or a shield-thrower in battle. It remains unclear whether truth was a defense (100-1). How often did mocked persons sue their enemy? Such litigation advertised the insult and suggested humorlessness (112). It might be easier and more pleasurable (Aristotle Rhetoric 2.26) in a rowdy performance culture to retaliate, to escalate to night street-violence (as Demosthenes argues) or in daylight.

Kamen’s fifth category of abuse unleashes the elephant in Athens’ insult agora. Revenge could be sought legally or extra-legally (thrashing, stomping, punching), running the risk of litigation. Hubris acts were open to a public lawsuit (graphê), that is, the law regarded such “exuberant, deliberately dishonoring arrogance” offenses as harmful to the commonwealth of the polis and to the immediate victim. Verbal and nonverbal assaults on person and honor multiply—think of gestures, looks, tone—attitude crucial! Somewhat oddly, no example of such a prosecution survives among many law-court briefs. While various speakers insist they had the elements of a graphê hybreôs, none chose that route (130), usually preferring the less risky private charge of outrageous behavior (dikê aikeias). After the bully Konon crowed over Ariston lying prostrate, behaving like a cock flapping his arms–arguably symbolic rape–even humiliated but anxious Ariston chose this path of lesser offense (Demosthenes speech 54, Against Konon). Hubris was difficult to prove because showing intention was essential. Moreover, losing a hubris suit opened one up to serious penalties. Demosthenes’ brief Against Meidias employs the word hubris 101 times, a script of vulnerability. But the lawyer and politician expresses the idea without running the risks of bringing a hubris suit.

How consequential were the insults of public mockery? Kleon, insulted frequently in Athens’ theater, himself insulted the Athenian generals (as not “real men”) when they were stumped about how to seize Pylos island from the besieged Spartans. Subject to mocking laughter himself in the assembly for his crude style and fatuous boasting (Thucydides Histories 4.27-8), he nevertheless maintained his popular support. After deserting immediately at the start of the battle of Amphipolis and being quickly speared dorsally, Kleon died ignominiously. Is the shaming death-scene that Thucydides wrote a malicious riposte by an enemy, since he was another Athenian general embarrassed defending Thrace (5.10)? Plato has Sokrates claim in court that Aristophanes’ comic mockery harmed his reputation (Apology 18c-19c). Joined to other parties’ irritation and humiliation having served as targets of Sokrates’ frequent and barbed ironic insults, it proved fatal to him.

Kamen regrettably does not treat the visual evidence that vase-painters produced in this period rich in daily-life satire. Many vases sketch the pleasures experienced in insulting out-groups such as barbarians, women, and slaves. We observe drunken (often aristocratic) symposiasts engaged in less than convivial, violent brawling, with or without impromptu weapons. Kamen purposely sidesteps epic forerunners of the Athenians–Homeric insults (D. Lateiner 2004: Homeric Insults. Dis-Honor in Homeric Discourse, San Diego). She could also investigate behaviors including threats and thrashing in contemporary Athenian historiography, tragedy, philosophical texts, and stylish pottery, even graffiti and curse tablets in a polis which was most civilized of the primitive and most primitive of civilized states. These sources illustrate the lush ecology of conceptually egalitarian Athenian and wider Hellenic kakology—the study of bad-mouthing and ancient gestural insults equivalent to “giving the finger.”

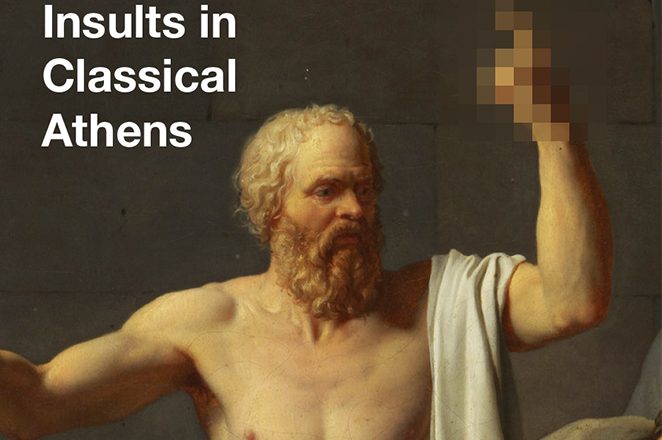

Speaking of which, Kamen’s only illustration appears on the cover: a detail from Jacques-Louis David’s 1787 painting, The Death of Socrates. Socrates, accepting the poison hemlock, sits in neoclassical colors with raised left hand and forefinger extended. The martyr’s neo-Classical gesture indicates either an appeal for rational (not emotional) attention from his weeping disciples or an appeal to the Olympian gods. On the “cheeky” cover, however, his hand has been pixelated, as if the publisher were censoring Sokrates’ Sicilian or American obscene gesture (extended middle finger, anachronistic for Athenians). Plato (Phaedo 117b) mentions Sokrates’ peculiar “look” (taurêdon, a downward bullish head-tilt)–but no gesture. Kamen has usefully hierarchized Attic insults and disparagement, but her analysis remains more legal than social.

Donald Lateiner

Humanities-Classics and AMRS Emeritus,

Ohio Wesleyan University

References

Insults in Classical Athens. By Deborah Kamen.. Madison and London: University of Wisconsin Press. 2020. Pp. xv, 258.