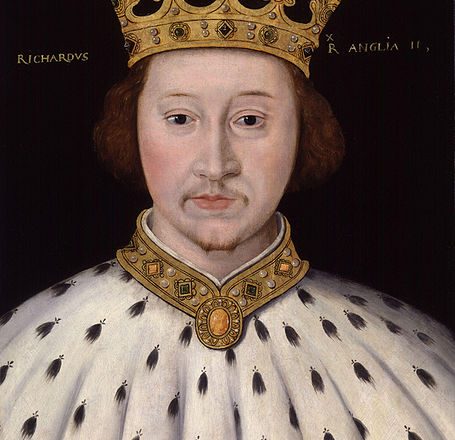

Richard II is a much maligned figure in history. Most people probably know him as one of two things, either as the tragic figure from Shakespeare’s play Richard II, or as the boy king of England. Historians instead know him as the tyrant figure who marks a turning point in political history. His death represents the changing of a dynasty and the beginning of the Early Modern Period in English history. Who, then, was this tragic boy tyrant and how did he become such a character in our history?

Richard’s story is deeply tied to both the politics and gender norms of the late medieval era in which he lived. As a boy, Richard was crowned king at the age of ten and thus denied any time period of youth in which he may have proved himself a man. Instead he became a figurehead for his council that ruled for some time in his name. Certainly, the standard which Richard was compared to was high, as his grandfather, the previous king Edward III, had been a prolifically manly man by medieval standards. Even so, Richard attempted to excel within the gender system. He received praise for his actions during the Peasant Revolt and led successful military campaigns in both Scotland and Ireland. In fact, his household records indicate that he spent more time and money hunting (a traditionally manly medieval activity) than even his grandfather had.

How then does Richard become the boy king in our history? That question is perhaps best answered by the actions of his usurper, Henry IV. Henry was Richard’s cousin, and about six months younger than him. Yet, Henry is associated with many of the manly attributes that Richard was not. Perhaps one critical factor is that Henry not only had a period of youth, but he had an exceptional one. During Richard’s reign, Henry stole his wife from a monastery where her brother-in-law had sent her, fought against rebels during the Peasant’s Revolt, fought in Richard’s Scottish campaign, received public glory for his role in the Battle of Radcot Bridge, fought in Spain, crusaded in the Baltic, toured Europe, and visited the Holy Land. During this time, he was also a prolific hunter and jouster. He and his wife also had many children whereas Richard and his wife had none.

Ultimately, once Henry had seized the throne and his cousin had died, he had the ability to hold great influence over the narrative of the kingdom’s history. Chronicles of this time praise him considerably and attack Richard in his most vulnerable area: his perceived youth. After all, in comparison to the feats of masculinity that Henry had performed Richard did seem like a boy. These perceptions certainly influence the way that Richard was perceived by future historians, but are they the truth? Possibly, but it is more likely that Richard was a figure whose public image was vulnerable and that his enemies exhibited expert precision in using this against him and thus left his reputation tarnished for fu- ture generations and historians.