This school year has seen an increase of AMRS events on campus. The latest of these, a student led recitation of the Old English epic Beowulf, took place on a fittingly dreary March day and attracted a sizable crowd of professors, majors, minors, and the casually interested. This event marks the revival of the campus tradition of hosting epic poetry “marathons,” which allowed students to experience foundational works of literature outside of the classroom and in the spirit of their original oral presentation.

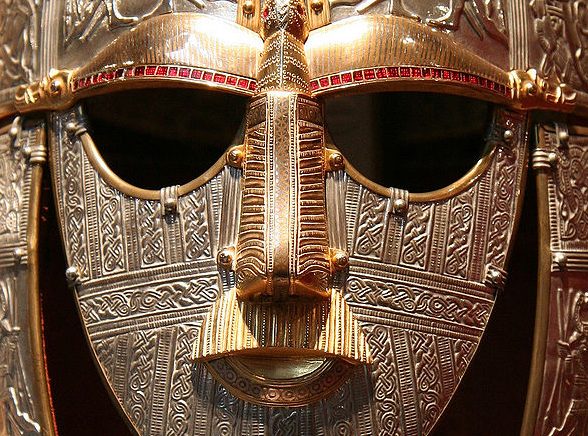

Though a rarity in modern times, the oral recitation of epic poetry has a rich history in cultures throughout the world. Both of the foundational works of Western literature, The Iliad and The Odyssey, are believed by most scholars to have been poetic accounts that were entirely memorized and recited by skilled bards prior to their being preserved in writing. Old English, German, and Norse epics (such as Beowulf) were similarly preserved through memory and performance, though many of these works were lost when the Germanic peoples of Northern and Western Europe were Christianized. Those poems and works which do survive—namely Beowulf, The Nibelungenlied, various fragments of sagas, and the two Eddas—are all that remain of the beliefs and attitudes of the ancient Teutonic peoples. Edith Hamilton, the renowned classicist, notes that the material for an epic that would rival The Iliad exists in the “somber grandeur” of the Germanic myths and poems. Unfortunately, these works never had a Homer to work them over in the way that the ancient Greek stories did. Nevertheless, she maintains that many of the stories are “splendid. . .the best Northern tales are tragic, about men and women who go steadfastly forward to meet death, often deliberately choose it, even plan it long beforehand. The only light in the darkness is heroism.”

Beowulf proves no exception. The fact that the poem survived at all is a miracle, as the only known manuscript copy very nearly was destroyed in an 18th century fire. After this, the poem was properly transcribed, edited, and translated until it entered the canon of English literature.

The edition used at the marathon reading was Seamus Heaney’s translation, which captures the somber, heavy characteristics of the Germanic epic described by Hamilton. The plot of the poem is carried by the heroic deeds of the Scandinavian prince for which it is named—in particular, his defeat of the monstrous terror Grendel, who has been mercilessly preying on the Danes and their king, Hrothgar. The heart of the poem is not only concerned with the encountering and overcoming of the monstrous, but also the manner in which one continues to live in the aftermath of such encounters. True to its origins, there is a certain fatalism which permeates the poem right up to its bitter end, culminating in Beowulf’s fight with a dragon and subsequent death. But this existential bent is what gives the Germanic poems their defining, memorable quality; that is to say, eventually there comes a time when courage, endurance, and great deeds prove not to be enough. Nonetheless, a true hero will choose to live by ex- ample and not yield, even in the face of death. Again in the succinct words of Hamilton,“for the poets of Norse my- thology. . .the power of good is shown not by triumphantly conquering evil, but by contin- uing to resist evil even while facing certain defeat.”