It is tempting to begin by writing “It all started in my Grade 12 literature class with Mr. Ames. . .” because there is a certainly some truth to that sentiment. As is likely the case for most of us, my first significant encounters with Shakespeare came in high school, whether it was acting in Othello in my Drama class (I’m not going to tell you what role. . .), or studying Hamlet, Macbeth, and the Sonnets in various English classes. Yet, unlike many who have gone down the academic path, I did not immediately make the jump from high school to college. In fact, other than obtaining two perfunctory vocational degrees in my twenties, it took me fifteen years to finally fulfill a long-latent love of literary scholarship and ultimately enroll in the full-time degree programs that have led to my pursuit of a Ph.D. at OSU.

After a brief stint at a community college, I was accepted to the undergraduate English program at the College of William and Mary, where I had the great good fortune to have the late Paula Blank as my advisor. A research seminar on Shakespeare’s Sonnets, co-taught by Paula and her colleague Thomas Heacox, opened my mind to a world of possibilities concerning the individual poems, and the work as a whole. It was then that I discovered my interest in textual anomalies in certain of the Sonnets. By the time I stared my Master’s at the University of Maryland, this interest deepened into more critical questions about the printing of the Quarto edition, and thanks to some excellent guidance from various UMD professors (not to mention the close proximity of the Folger Shakespeare Library), I arrived at what is now my primary research interest.

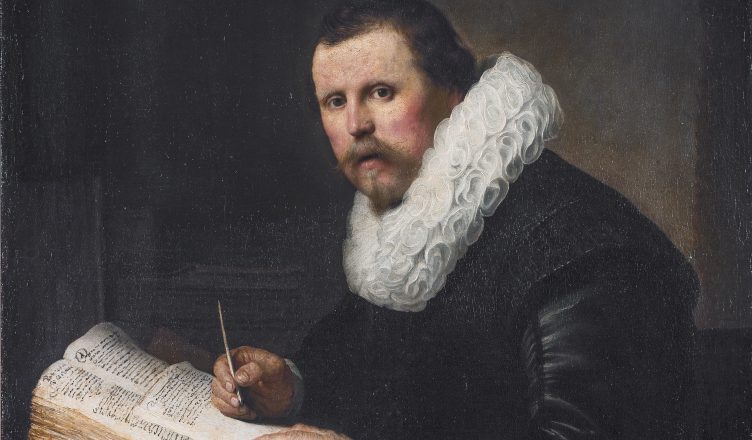

When the Quarto edition of Shakespeare’s Sonnets was first released in 1609, it was largely ignored by the populace. Theories abound as to why this is the case, but what I find most interesting is that the next edition released, publisher John Benson’s Poems Written by Wil. Shake-Speare, Gent., was remarkably popular. In spite of (or just as plausibly, because of) Benson’s stripping of the poems’ distinction as sonnets (often fusing multiple sonnets together), his replacement of numerical titles with textual ones, his reordering of the poems, and—most egregiously, by modern standards—his omission of eight of the sonnets altogether, records indicate that his edition sold surprisingly well. All of this has been well-documented, of course, but further research revealed that with one minor exception, Benson’s edition—not the original Quarto—formed the basis of all subsequent editions of the Sonnets until 1766. For years I was convinced that, as many scholars over the decades have posited, Benson’s actions were heinous; yet over the past year and a half upon gaining a much broader understanding of book history and early modern publishing practices, I have come to believe that Benson does not deserve to be demonized to such a degree. In plainest terms, what he did was a perfectly acceptable, if slightly morally ambiguous, act of a profit-seeking publisher. And it clearly paid off.