Abandoned small towns throughout the Southeastern Appalachian region of Ohio share roots deep within the mining industry. These towns are commonly called “Little Cities of Black Diamonds,” honoring their historical ties to coal, industrialization, and once flourishing economies.

Perry County, Ohio, is among these Little Cities of Black Diamonds. Once an industrial hub consisting of multiple coal boomtowns, Perry County and its residents have faced economic declines since the mid-1900s. Decades after these mines were closed, coal has continued to affect generations of residents.

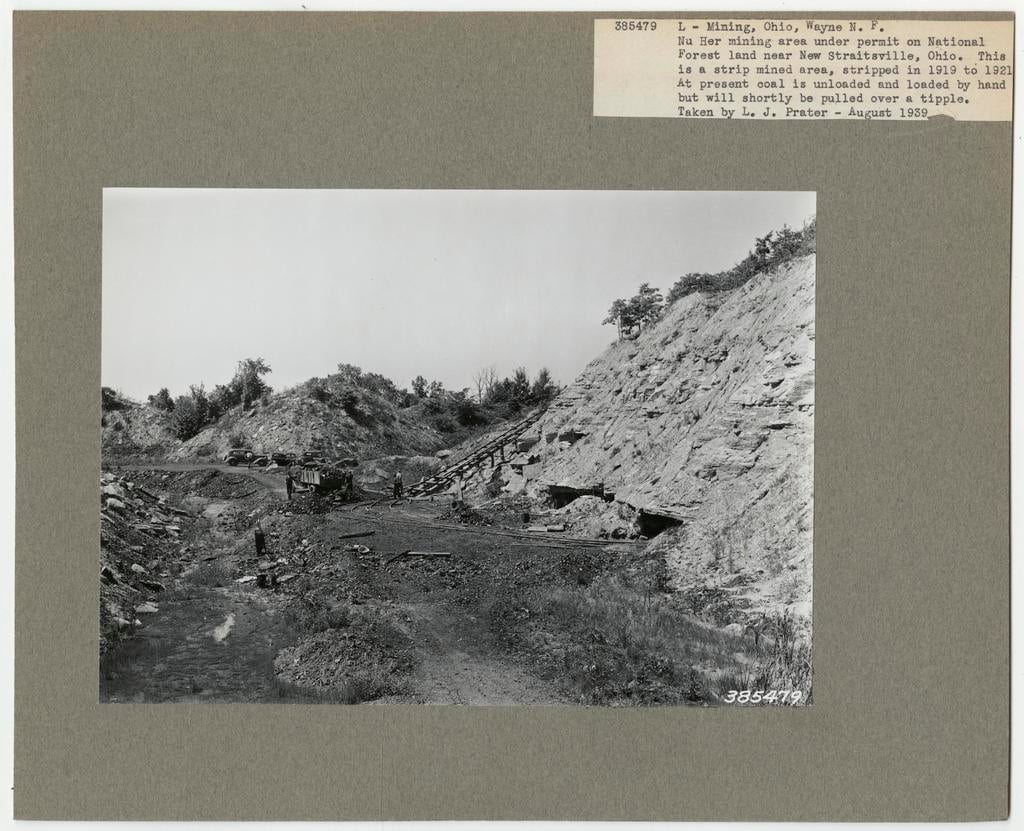

In the early 1800s, rapid industrialization combined with a lack of government regulation led to a boom in the coal industry in the Appalachian United States. The exact date coal mining reached Ohio is unknown because the industry was completely unregulated. But by 1820, coal mining had spread to 20 Ohio counties and, by 1870, to 30. The United States Forest Service reports that between 1820 and 1920 an estimated two billion tons of coal were mined from Ohio. By the late 1800s, Ohio was among the leading coal-producing states, employing thousands of workers, and fostering the development of towns dependent on the coal industry.

By the time government regulation caught up with the Ohio coal industry, it had been active for well over 100 years. In 1947, the Ohio legislature made its first attempt to regulate the production of coal, although citizens had been lobbying for better working conditions continuously for years prior, even creating one of the earliest labor unions, based in Shawnee, Ohio, in Perry County. Based on the Division of Reclamation reports from Ohio government documents, the 1947 legislation vaguely stated that conservation of land in coal mining areas would be assigned to the Chief of the Decisions of Mines in the Department of Industrial Relations, without identifying much of what this meant in terms of rules around coal mining restrictions. In the decades since, additional regulations have been added to protect coal miners; however, the environmental damage surrounding coal communities cannot be easily erased, which has led to cycles of negative health effects and poverty within the region.

The coal mining empire stretched across the Appalachian region and reigned over humans and their land. After the empire’s peak in Ohio in the 1970s, technological advancements, increasing environmental regulations such as the Clean Air Act, and competition from other energy sources led to the ultimate industry decline. Ohio’s coal industry fell apart, leaving more than 4,600 identified abandoned underground coal mines, and an estimated 2,000-4,000 abandoned mines to be unmapped. Ohio Coal reports that today, there are only 80 active mines.

However, the Big Coal industry’s legacy lives on. Today, 22,000 acres of abandoned mines run below Ohio land, and 20,000 acres of surface mines strip Ohio’s Appalachian mountaintops.

This has led to irreversible damage to human health due to environmental hazards such as landslides, erosion, toxic mine spoil, acid mine damage, and more. Once home to thriving mining towns such as Shawnee and New Straitsville, Perry County and its residents now face economic hardships. 15.5% of Perry County residents live in poverty, compared to the Ohio-wide average of 13.3%, based on information from the US government census report.

This issue is mirrored throughout Appalachian Ohio; Athens County borders Perry to the south, where 21.6% of residents live in poverty. In the greater Appalachian region, the poverty rate is 14.3%, higher than the national average of 11.1%.

This widespread economic distress can be traced directly to the region’s historical reliance on coal mining, compounded by the environmental and industrial challenges left in its wake. Generational poverty is a persistent problem, where those who historically relied on mining jobs for incomes for themselves or family members, are now limited to few stable economic opportunities. Environmental damages discourage new industries and investments in the area, perpetuating a cycle where the only remaining jobs are typically in service or industrial spheres, offering little chance for upward mobility or generational wealth accumulation.

Meanwhile, infrastructure, such as healthcare and educational facilities, in Perry and Athens counties remain underfunded, limiting residents’ access to fundamental social services. In 2022, Perry County faced an increase of 11.9% of residents who did not have access to health insurance, highlighting the continuous and long-term economic effect of the industry’s status on the region.

The Ohio government has continued to develop projects to support development across Appalachian counties, such as the Appalachian Community Grant Program which allows counties to apply and receive funding for support in the infrastructure, workforce, education, and healthcare spheres of their communities. This program is relatively new, however, having only been established in 2023.

Although these regions have a deep-rooted history of environmental destruction and marginalization through repeated governmental neglect, Southeastern Ohio and the broader Appalachian region rely on remembrance and cultural identity within the coal region. Sites such as the Little Cities of Black Diamonds Historical Society and Tecumseh Theatre in Shawnee work to maintain remembrance of their past and pave for a more equitable future. In the next post, culture and connection to history in Southeastern Ohio’s mining towns will be explored.