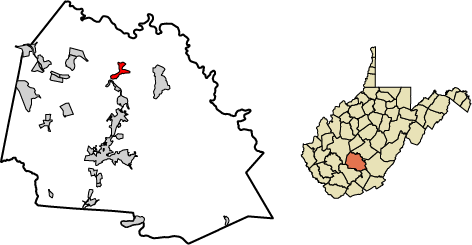

West Virginia is known for its natural beauty and remote communities, nestled in the Appalachian mountains and valleys. Minden, West Virginia is located in the center of the state, lodged between two peaks, and is home to 250 dying residents.

In Minden, nearly 36% of residents have been diagnosed with a form of cancer.

Minden is situated within the central Appalachian region, an area also called the “Cancer Cluster”; the high rates of cancer and other chronic illnesses are the result of environmental hazards, such as toxic waste in the air, soil, and water due to chemical runoff from the coal mines, industrial sites, and increased manufacturing.

A story mirrored in many Appalachian communities, Minden was a once thriving mining town. In 1970, Minden’s population was around 2,000; today it is less than 15% of that. The trend of declining population is attributed to a lack of economic opportunity due to the decline of the Big Coal industry, leading to persistent and extreme poverty; this creates a vicious cycle in Appalachian communities, where individuals are exposed to hazardous chemicals but are unable to seek help due to the lack of resources and governmental aid, perpetuating a cycle of poverty and negative health effects.

In Fayette County, where Minden is located, 24.1% of residents do not have health insurance, and 21.5 % of residents live in poverty.

From 1970 to 1984, a coal mining equipment manufacturer, Shaffer Equipment Company, was based in Minden. Shaffer manufactured multiple types of transformers, capacitors, and other distribution devices, all produced using oil-containing polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs. PCBs are highly hazardous chemical compounds that can cause various health effects, such as cancer. PCBs were banned by the federal government in 1979; however, these chemicals linger in exposed regions due to the time it takes them to break down. Areas exposed still test positive for PCBs decades later. PCBs travel through and contaminate entire ecosystems due to a chemical makeup that allows them to be transported through water, soil, and plants, moving throughout the food chain.

Due to Shaffer’s mismanagement of manufactured materials, the Minden community was exposed to dangerous chemicals. Residents were unaware of these threats.

In 1984, the West Virginia Division of Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Agency investigated the site and found that was soil was positive for PCBs. Between 1984 and 1991, soil removal actions were conducted. Through two remediation processes, 4,735 tons of contaminated soil were removed from Minden and transported to a chemical waste site in Alabama for disposal.

Unknown to residents, these contamination relief efforts were unsuccessful. A report issued by the EPA in 2024 states that, due to rainfall and flooding, PCB-contaminated soil spread through the environment by deposits carried downstream. The report also states that community members claimed that PCB contaminated sediments were improperly and illegally disposed of throughout Minden, in abandoned mines, pits, and on roadways.

Noting the correlation between high rates of terminal illness and environmental contamination, residents pushed for additional testing. Eleven community members joined forces to form Concerned Residents to Save Fayette County, a grassroots community organization designed to spearhead requests for federal aid.

However, Minden resident’s pleas for help were widely ignored due to the misleading data about the cancer mortality rate in the area. Minden houses zero medical facilities, meaning that most cancer patients under medical care will die away from home. And since mortality rates are recorded where an individual dies, data was skewed around Minden to hide an already invisible killer.

Eventually, the EPA would conduct additional removal actions between 1990 and 1993, consisting of additional soil testing and removal of identified contaminated soil. Then, in 2001, following a fire on the removal site, the EPA conducted a third removal action which consisted of installing a barrier cap over the PCB contamination and buildings, with surface water drainage systems to redirect runoff away from the contained site. Yet the cancer diagnoses continued.

After continuous attempts to contact the West Virginia Division of Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Agency, residents finally received a federal response in 2017, leading to the collection of more soil samples. Testing showed that the area was still contaminated by PCBs.

In 2019, the site was finally added to the National Priorities List under the Superfund Program, becoming site number WVD988768909, SHAFFER EQUIPMENT / ARBUCKLE CREEK AREA SUPERFUND SITE.

Beginning on March 13, 2023, the EPA held a 30-day public comment period to allow community involvement within the new removal action plan. Then, on March 21, 2023, the EPA held a public meeting at the New Beginnings Church in Minden to inform local officials and citizens about the proposed cleanup plan. According to EPA Administrative Records, several residents requested permanent relocation. The EPA responded that “Permanent relocation is only considered in cases where contamination poses an immediate threat that cannot be mitigated or remediated, implementation of remedial measures would require the destruction of homes, or the cleanup requires residents to be temporarily relocated for over one year.”

However, the residents in Minden distrust the effectiveness of promised cleanup efforts due to numerous previous failures, and the growing cancer rates in their community. The March 21 transcript records their frustration:

“What makes you think you’re going to get rid of it now? What are you going to do, burn it again?”

“It makes it seem like the comments that the community has really doesn’t matter. So why do we even make comments? Why do we make comments? Because if that’s what you want to do, that’s what you’re going to do. Because in all reality, you’re still not listening or you’re listening in your ear, but you’re still not listening what the people here want.”

“The question is when are you going to stop telling us you’re going to do this, do that and help us when you’re not doing nothing to help us?”

“Why in the last 17 years was not EPA overseeing what was happening to the people or the site? What about all the cancer then and PCB levels?”

Minden, however, is not alone in the struggle for safe and habitable living conditions. This is a human rights issue, amplified across Appalachian communities, where socioeconomic hardship is compounded by environmental hazards. Applachaia’s isolated communities lack access to proper healthcare services, with residents forced to travel for care; when coupled with few preventative care options, cancer and other terminal illnesses become silent epidemics.

Although residents are now aware of the looming health threats, many are unable to leave. Simultaneously, the presence of unsafe living conditions discourages new investment or economic opportunity, preventing the kind of economic stability that could encourage future cleanup efforts or relocation of residents. All the while residential values in the community drop, further exacerbating the cycle.

In the United States, 12.5% of residents live in poverty. In comparison, the poverty rate in the Appalachian region is 14.5% and, in Fayette County, 21.5 % percent. We see this link amplified in the coverage of the cancer mortality rate: the annual death rate from all cancer types is 12.5% higher in Fayette than in counties without persistent poverty, according to data from the National Cancer Institute.

Historically, the Appalachian region has been aggressively harvested for economic gain by industry at the expense of those living within the region. Central Appalachia’s deep history within the Big Coal industry, rooted in harmful mining practices such as mountaintop removal, continues to impact residents. Once economic opportunity via environmental degradation is complete, these regions are typically abandoned, leaving empty mines, contaminated land, habitat loss, and landscape destruction. This creates a cycle of long-term job instability, declining property values, and displaced social structures.

Today, Minden is at a standstill; residents are unaware of the future of their community, subjected to living at the mercy of structures that have failed them so many times before; at the hands of those who poisoned their plateaus, and forced them to wade through polluted streams they call home.