The time when I read Giovanni’s Room, an extraordinary novella by the even more extraordinary James Baldwin, could have been the worst possible moment – but, surprisingly, it might have turned out to be the best. I was living through my very first real winter – all the previous eighteen had been a collection of only slightly chillier and less rainy summer days, as every winter is in Rio de Janeiro. I was cold all the time, I missed going outside not wearing a coat, I missed speaking my first language in which I manage to sound way smarter than in my second, I missed being in a big city, fighting with my sister and always winning because she is terrible at rhetoric, driving by the beach every day, and I desperately, indescribably missed my dog. In more obvious terms, I was very, very homesick. And then, by chance, I found myself reading a story that is, among so many other beautiful, crushingly sad things, about being away from the place you call home. I loved every word and every minute of it.

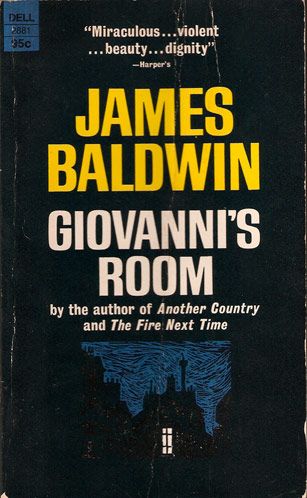

Giovanni’s Room is the story of David, a young American man living in Paris, as told by himself in a dark, quiet night as he looks back at everything that has led him to this very loneliness. His recalling of the past mainly surrounds his complicated, harrowing relationship with an Italian bartender named Giovanni, and how this affair forces David to face the questions about himself and his sexuality he has avoided asking his entire life. The themes of this book range from love and sexuality to shame and family, but the central problem that lives at the heart of the story is, in essence, the main character’s struggles with accepting his identity, and how they affect and inevitably alter both his fate and Giovanni’s.

What made this book perfectly cathartic for the moment I read it is how intrinsic to David’s struggles is the fact that he finds himself very far from home. He went all the way across the ocean to run from himself and his desires, but in Paris, though he is a perpetual stranger free to act on his urges because no one knows him, his secrets remain the same. There is something excruciatingly relatable in the paradox of needing to leave home to be who you are, but not feeling like yourself unless you are at the place you call home:

I ached abruptly, intolerably, with a longing to go home; not to that hotel in one of the alleys in Paris, where the concierge barred the way with my unpaid bill; but home, home across the ocean, to things and people I knew and understood; to those things, those places, those people which I would always, helplessly, and in whatever bitterness of spirit, love above all else.

There are a number of remarkable passages in this book that astonishingly illuminate the themes of identity, shame, and sexuality that characterize the story and David’s relationship with Giovanni, but this one, in chapter three, was especially captivating to me – perhaps simply because I desperately related to it. David’s homesickness is often a quieter, more underlying issue in awe of the terrifying greatness of everything being with Giovanni teaches him about himself, but to me it still seems that the true understanding of the story is found within everything this passage represents. David wants love and to not feel shame, but to him these are not two wishes that can come true at the same time, and his homesickness is the essence of this dilemma: he wants to be somewhere he knows, but where no one knows him, and the fact that this is impossible is the reason for the discomfort that characterizes him throughout the novella. This passage truly illuminates the paradox that is so fundamental to the character – and that, above all else, is what I relate to so much.

The fact that I shared with David this desperate longing for home, however, is hardly the only reason I was able to so deeply understand the pain this passage reflects. There is something very striking to me about his voice; he is quite clearly an agent narrator, a participant in all the events of the story, consistently causing things to happen or suffering the consequences of things that already have happened. His presence is, undeniably, a driving force of the plot. But when we take a more attentive look, there seems to be another aspect hidden beneath the surface that is highly responsible for the melancholy and emotion that comes through the words: despite his protagonist status, more often David comes off as an observer narrator. The story is told through the lens of a lonely night he spends facing the consequences of everything that has already happened, and the fact that he sees the entire picture is reflected in the mournful way in which he narrates. He is extremely self-aware about the meaning of his actions and thoughts because he knows the entirety of consequences that followed. His knowledge – which is much more than the reader’s, because of his position – creates, throughout the entire novella, the feeling that he is an observer of his own life, quietly and slowly watching everything fall apart as if there was nothing he could do – because, really, it has already happened, and there isn’t anything he can do.

Another aspect responsible for the palpable representation of feelings in the story is the fact that Baldwin absolutely masters the use of emotional language and never fails to represent the intensity of the whole spectrum of feelings David faces as the story progresses. The author exceptionally explores, through the use of language, all the shades and layers of David as a character. Specifically his use of adverbs of intensity – such as abruptly, intolerably, helplessly, as seen in the passage – is a strategy present during the entirety of the story, and it proves itself very successful in faithfully and intensely transmitting to the reader the true depth of the character’s feelings as he tells his story. In the chapter three passage, for example, this use of adverbs perfectly translates the desperation David feels – it is more than just a wish or a want; it is almost a physical craving, and, with the right words and an author like Baldwin, we are able to understand – and perhaps even feel – this desperation beyond the simplicity of assembled letters that create familiar words.

It’s a common advice given to writers: the more specific your writing gets, the more universal it can become – and this is exceptionally proven by Baldwin in Giovanni’s Room. David is an American man living in Paris in the fifties, a repressed and generally sad person who wants, more than anything, to go home. My own life is set seven decades later; I am not a man, I have never been to Paris, I am definitely not American, I consider myself neither repressed nor unhappy, and, however excruciatingly homesick, I love life away from home, and the quiet feeling that comes with it, that, day by day, my world grows bigger. And yet, despite all that I do not have in common with David, there is something utterly recognizable in every detail of his journey. Both on the good days when I know without a doubt I made the right choice to move a twelve-hour plane ride away from home and on the bad days when it’s very cold and very easy to forget the previous blissful certainty, I, too, miss every aspect and every inch of home. I miss the people who speak my language and share my accent, the room with burgundy walls in the apartment where my family waits until December, the tree that stands steadily and casts a long shadow in front of my building, every detail and every corner, that, particularly lovable to me or not, I will always love desperately, because, in their collectivity, they mean home.

That is what makes Giovanni’s Room such a remarkable read; anyone – whether or not they have been to Paris, had a secret relationship, moved away from their family, or fallen in love with a bartender – understands what the idea of home is. It may not be a house or an apartment or a big city or small town, but it inevitably is something – more than often within us, rather than without – that is perpetually recognizable. It may be your childhood bedroom, your grandmother’s backyard, the smell of your favorite food, the sound of your favorite lullaby, or the park where you had your first kiss. It may be a place, a story, or a fading memory – in spite of whatever details, there is, in David’s longing for home, something utterly recognizable within ourselves.