Written by Grace Lilly.

This past semester, I had the privilege of attending Queen’s University Belfast through the Irish American Scholars program. When I started looking into study abroad programs my sophomore year, Irish American Scholars stood out to me not only because it was the most affordable, but also because it was in Northern Ireland. I have always been interested in Irish culture and history. The two periods that interest me the most are the Troubles and the Medieval period. Despite being centuries removed from one another, they were both defining eras in Ireland’s colonial history. While at Queen’s, I was able to take two modules related to these interests: a history course called “War, Politics, and Identity in Late Medieval Ireland, c.1166-c.1521” and an English course called “Representing the Working Class: British and Irish working class life in twentieth and twenty-first-century fiction, drama and film”.

My module on medieval Ireland truly felt like a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity as a student of Medieval Studies in the U.S. Through Ohio Wesleyan’s AMRS program, I have had the opportunity to learn a lot about medieval history and literature from around the European world. Ireland, however, has not been represented much. If discussed at all, it is often in relation to England and the construction of the British Isles. Before finding this program and this module in particular, I thought that my best bet for exploring medieval Ireland would be through personal research or graduate-level studies. I felt exceptionally lucky to be able to attend Queen’s and take this course with an expert in the field, Dr. Simon Egan. The module gave a complete overview of the medieval era, starting when Anglo-Norman colonizers began arriving in Ireland in 1167 and moving through the centuries to the period of Gaelic resurgence in the early 1500s.

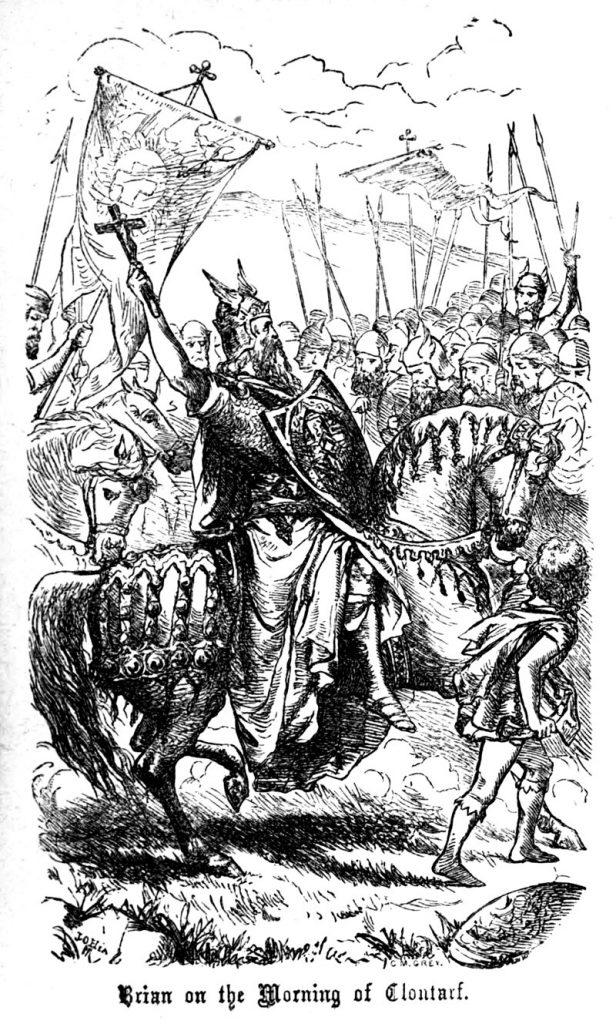

The beginning of the course was particularly interesting as we discussed what Gaelic Irish life looked like before the Anglo-Norman intervention. The island was divided by four major provinces: Leinster, Munster, Connacht, and Ulster, and ruled by a patchwork of competing royal lineages. These kingships included the Uí Chonchobhair (O’Connor) kings of Connacht, the Uí Bhriain (O’Briens) of Thomond, the Meic Lochlainn (MacLoughlins) of Ulster, the Meic Cárthaigh (MacCarthys) of Desmond, and the Uí Chennselaigh of Leinster. It was a time characterised by boundary wars but also a vibrant Gaelic culture. This period remained incredibly important as Anglo-Norman colonizers relentlessly attempted to eradicate Gaelic culture and language. In times of Gaelic resurgence, it was most interesting to see the ways medieval Gaelic lordships would continue to tell the stories of their predecessors, often claiming an almost mythic ancestry from the original Uí Chonchobhair (O’Connor) kings of Connacht or the Uí Bhriain (O’Briens) of Thomond. They would also reinstate practices of the old kings by continuing the practice of sending sons to live with other aristocratic clans or, most notably, practicing Brehon law. Brehon law is the ancient legal system in Gaelic-ruled Ireland that emphasized social hierarchy and restitution over state regulation. I think that one of the most fascinating parts of this era was the later medieval period, when many Anglo lords were sent to Ireland to conquer the land and instill English law, but began assimilating to Gaelic culture after decades of strained contact with England. They embraced the Gaelic-Irish language, artistic traditions, and occasionally Brehon law. These conversions or attempts at preservation were considered major threats to the English government and were often met by major restrictions whenever they started popping back up. While the course ended at a time in which Gaelic power was on the rise in the 1500s, it was clear from around the 13th century that total recovery would most likely never be made.

Despite this, Irish people have never really ceased in their fight for freedom from the British government. I have a serious lack of knowledge about what Ireland was like starting in the 1550s up until the early 20th century, but, evidenced by the fact that Gaelic culture still remains and most of the island was finally able to gain its independence in 1922, it is safe to say that the fighting spirit has never gone away. This is also evidenced more recently by the Troubles, spanning from the 1960s to the late 1990s, when the Catholics of the North tried to rise again against the British. We did not specifically cover this in my Representing the Working Class module, and while I am not certain about why, I mostly think it was because most students at Queen’s would have been born near the end, with parents living through the ordeal. We did speak about several stories that mentioned the Troubles or took place after the fact and related to the endless traumas resulting from the period. Out of the twelve works covered in this module, six were set in Ireland, three in the British-occupied North. The final book we read and my favorite of the module, Close to Home by Michael Magee, was set in West Belfast and discussed the deep-seated trauma of families living in the North of Ireland, specifically that of Catholics. Gaining the knowledge that I did from these books and then being able to walk around the locations they discuss made all the difference to my learning experience. I definitely annoyed my friends as we walked around City Center, and I brought up specific passages or moments from Close to Home that took place there.

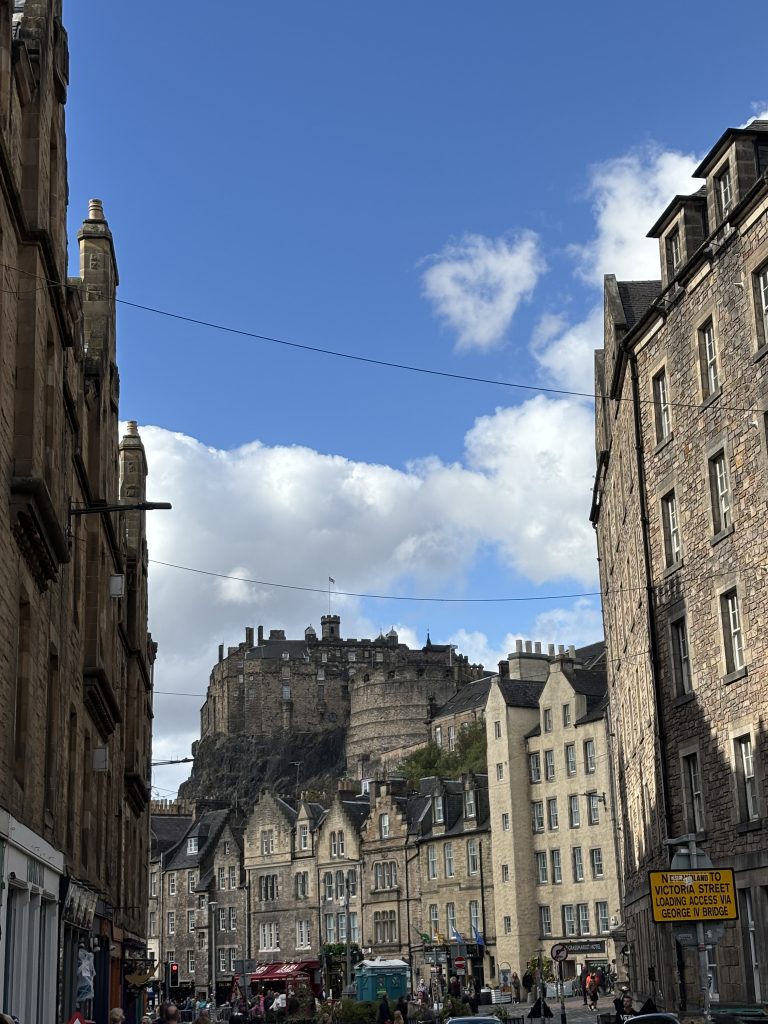

Similarly, there was nothing that could beat being able to study the island’s medieval history and then go view the relics that still remain firsthand. The Belfast Botanical Gardens were between my dorm and the academic center of Queen’s. I got to walk through them every day and walk past the Ulster Museum, which had a large collection of ancient, medieval, and modern Irish artifacts, mostly from the Ulster province. Any day of the week, I could walk into the free museum and see what I was reading and learning about right in front of me. I also got to visit several medieval locations, such as Dunluce Castle, built in the 12th century and featured as Pyke in HBO’s Game of Thrones. I viewed the Book of Kells at Trinity College in Dublin, and on a trip to Scotland, I visited Edinburgh Castle, built in the 11th century, and Blair Castle, built in the 13th century. It was wonderful to visit these monuments and have a real idea of the history they hold.

I was extremely lucky to take courses that specifically related to my surroundings, but I would not want to do it any other way. I learned material that I likely would not see in American classrooms, got firsthand experiences with history that is not accessible in the same way in the U.S., all while living in an incredible new city and making lifelong friends. Studying abroad was easily one of the best opportunities I have ever been offered, and I could not imagine life now without that experience. I encourage any English student with an interest in a specific region to do what they can to visit there while still in undergrad. It provides such a rich experience that is extremely hard to replicate once graduated.

Grace Lilly is a Junior at Ohio Wesleyan, majoring in English: Literature and minoring in Medieval Studies. She hopes to one day continue her education in Archive Studies and be able to work firsthand with the stories she loves to read.

Featured Image: Dunluce Castle

Images: Illustration of Brian Boru by John Fergus O’Hea, 1867.