When a person thinks of the concept of chivalry, they likely think of knights and fairy tales, or perhaps the modern idea of being chivalrous towards women, such as holding open a door or giving up a seat. One might even think of the phrase “chivalry is dead” and think exclusively of an absence of ‘gentlemen.’ Regardless, to many it would seem like a concept far removed from them, if they even consider it as a real concept, which some might not. They might imagine it as a concept invented exclusively for a certain type of fictional story.

However, chivalry was a real part of people’s lives in the medieval period and went far beyond being just a concept. Chivalry was a set of cultural and societal ideals and norms that shaped the behavior of the upper class. It was deeply rooted in society and daily life. Aspects of secular chivalry included concepts like fellowship, honor, service to the king, noble lineage, courtesy, and courage. Violence is also a known part of chivalry, largely because of the ways violence was connected to their secular values. For example, men would gain honor for showing prowess and courage in combat.

The church wanted to curb and direct some of the more violent behaviors and practices of the knights. The church introduced the ideas of the Peace of God and the Truce of God. The Peace of God, introduced in the year 989, identified three important things as qualifiers for excommunication: “taking ecclesiastical property by force; plundering agricultural resources from peasants; and attacking unarmed clerics” (Head, 656).1 The Truce of God, introduced in the year 1027, was intended to limit violence during specific times. For example, from sunset on Wednesday to sunrise on Monday, “During those four days and five nights no man or woman shall assault, wound, or slay another, or attack, seize, or destroy a castle, burg, or villa, by craft or by violence” (Bishopric of Terouanne, Truce of God).2 While both the Peace of God and Truce of God were not originally developed for the purpose of redirecting chivalric violence, they were repurposed through rhetoric to combine ecclesiastical and secular actions.

With these efforts of prevention, it is understandable that there were often tensions with the secular practice of chivalry and the aims of the church. Tensions between the church and the chivalric code before religious intervention were quite common, especially as the church, too, was a fundamental part of daily life. The tensions that existed do not mean, however, that those who were engaging with traditional chivalry were entirely removed from the church. Kings and knights were pious; however, they did not consider themselves entirely bound by religious ideology and constraints. Rather, the ideology surrounding chivalry, which they considered a part of their identity, had distinct values that would take precedence over the church’s values.

The crusades furthered this combination of secular and ecclesiastical actions. In part, by aiding in reconciling ideas held between the secular and ecclesiastical that previously were unable to coexist. Violence before had gone against church values such as mercy, compassion, and protection of the weak. Violence would often place the individual above the holy. Rather than following religious teachings, violence would be enacted over individual honor and personal glory. The church jumped on the chance to channel violence into something they could deem “appropriate”, and they did that through creating a narrative of “holy wars.” If the violence was done in the name of God, with the intention of protecting other Christians and the holy lands, it was righteous. The crusades also altered the narrative around divine salvation. Previously, another tension between the church and traditional chivalry was that for knights, the possibility of salvation seemed hard to reach with the violence inherent to their positions. Pope Urban II’s speech regarding the First Crusade made a specific note that those who took up arms for Christianity would have their sins absolved and their souls saved.

After the crusades, the groundwork was laid for a more cemented intersection of secular chivalry and the church’s ideology. The church and those affiliated with the church wanted to take the opportunity presented by the crusades to push the narrative combining the ecclesiastical and secular. Literature based around a more pious version of chivalry was being widely produced, though often from a clerical view, as they were the ones who tended to be educated. They wrote with the purpose to persuade others about their ideals surrounding chivalry. They argued that knights needed to have as much faith as they did courage. They also emphasized that knights were expected to have a moral code; it was not just about their skill as a warrior, but what they were fighting for. However, this does not mean that chivalry and knights became pious to the degree that the church wanted overnight. Nor does it mean that there was a complete absence of secular authors. One of the most famous chivalric tales, that of King Arthur and his knights, was written by an entirely secular author, Sir Thomas Malory. This does not mean Malory wasn’t religious, only that he was a knight first, rather than a member of the clergy.

Malory’s works were an example of literature that did not aim to erase the journey and complexities of chivalry, as it combined the secular and ecclesiastical. One notable example of this is Sir Malory’s tale of “The Holy Grail”, which places a large emphasis on Lancelot and his struggle to balance the demands of Christianity with his more traditional and secular knightly values. Lancelot tries to remain pious, and he wears a shirt made of hair as penance for his sins. However, Lancelot is not able to see the grail fully as a result of his affair with Queen Guinevere, and he consistently demonstrates a failure to trust God over his own strength. This offers a unique insight into the way people within the medieval time period, even after the crusades, struggled and thought over the development of religion into the more traditional and violent aspects of chivalry. It shows the same understanding that many modern historians hold, which is that while chivalry remained a moral and social code, it was a flexible one that evolved over time as values, culture, and the movement of history demanded.

- Head, Thomas. “The Development of the Peace of God in Aquitaine (970-1005) | Speculum: Vol 74, No 3.” The University of Chicago Press Journals, www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.2307/2886764.

- “Medieval Sourcebook: Truce of God – Bishopric of Terouanne, 1063.” Internet History Sourcebooks: Medieval Sourcebook, Fordham University, sourcebooks.fordham.edu/source/t-of-god.asp.

Featured Image: Two Knights Fighting in a Landscape by Eugène Delacroix, 1824. This work is in the public domain.

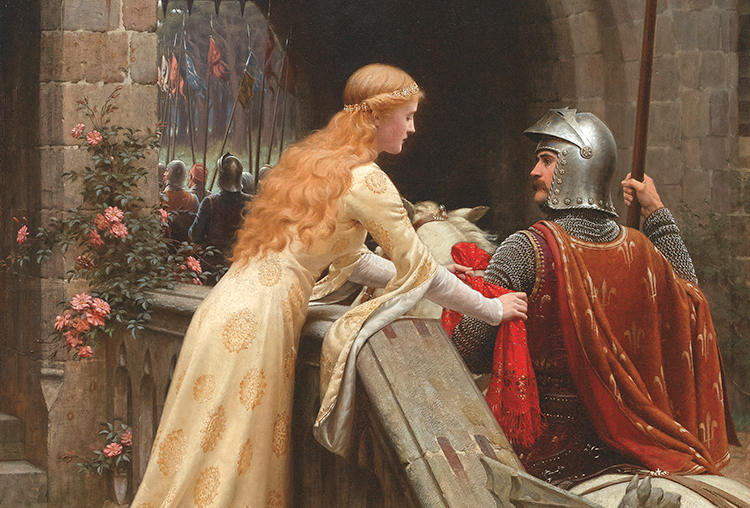

Images: God Speed by Edmund Leighton, 1900. This work is in the public domain.

The Taking of Jerusalem by the Crusaders, 15 July 1099 by Émile Signol, 1847. This work is in the public domain.

“Illustration from page 38 of The Boy’s King Arthur: “I am Sir Launcelot du Lake, King Ban’s son of Benwick, and knight of the Round Table.”, by N.C. Wyeth, 1922. This work is in the public domain.