Lucifer is an infamous figure, and writers imagine him in a stunning range of ways. Dante Alighieri’s take on the devil is seen in his medieval work Inferno, which explores nine circles of hell, culminating in the last, in which Dante sees Lucifer face to face. With how well-known Inferno is, one might expect Dante’s portrayal of the devil to be the standard biblical depiction of Lucifer; however, Dante’s portrait is quite distinctive both from that imagining of Lucifer and from other contemporary portraits of his time. Why then does Inferno, in its portrayal of Hell and the devil, remain such a significant part of the literary canon?

Inferno was written in the 14th century. Prior to the 14th century, the most common portrayal of the devil would have been derived from biblical descriptions, such as Lucifer as the prideful fallen angel. This is an imagining of the devil that has remained popular. Some theologians would specifically state pride as the reason for Lucifer’s rebellion and subsequent fall. It is interesting, then, that pride is not the circle that the devil resides in, in fact, it’s not even mentioned in Inferno at all, but rather in Purgatorio.

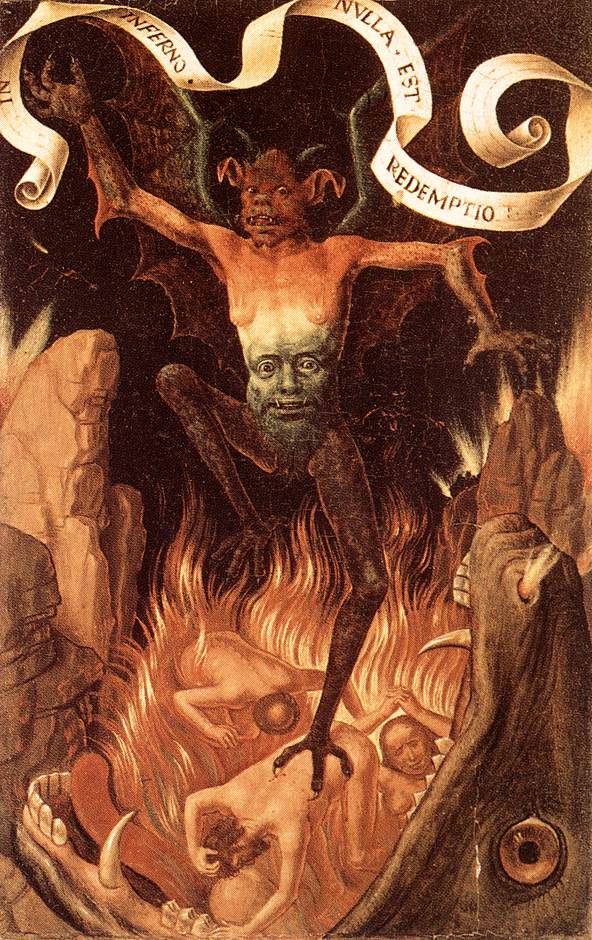

With this difference aside, within the context of the 14th century, Dante’s devil does share some similarities with portrayals of the time. At this point, with the movement away from the ‘fallen angel’ portrait, the devil became a more grotesque, beastly figure. For example, in the 14th-century manuscript, the Smithfield Decretals, the devil is shown as having claws, an anthropomorphic head, and, oftentimes, featherless wings and a tail too. In many images, the devil is shown to tower over regular humans. Similarly, Dante’s devil is depicted as a giant, with bat wings, three heads, with each head eating a sinner. The depiction is grotesque and certainly monstrous, as would be fitting of the time, if not even a little extreme.

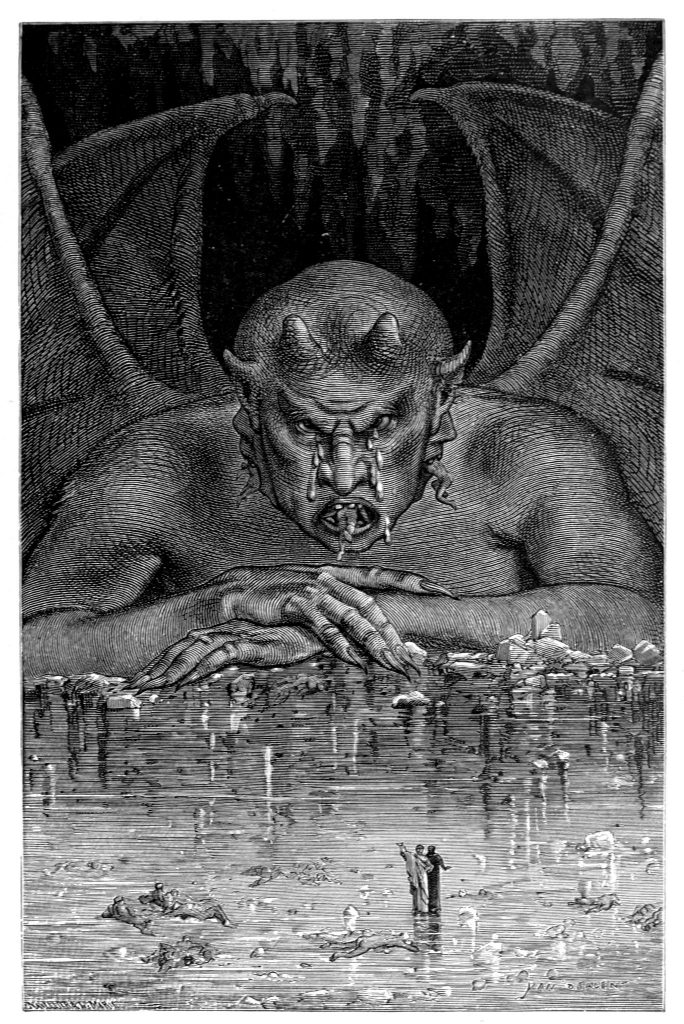

However, Dante’s devil differs drastically in notable ways from both the medieval period and our own modern perception of the devil. Dante describes Lucifer, “[w]ith six eyes…and three chins” down which “trickled the tear-drops and the bloody drivel” coming from his eyes. (Canto 34, ll. 53-54). This is interesting because the devil is oftentimes portrayed as confident and in control, ruling over Hell, but in Dante’s narrative, he appears to be a victim of Hell and suffers just the same, as all the other damned souls Dante encounters do. It is also unique in the sense that the medieval perception of Hell often includes an eternal fire, as does the modern idea of Hell. However, Dante imagined the devil as trapped in ice. This furthers the absence of power the devil holds in what should be his own domain.

It is also important that the devil resides in the ninth circle, the worst circle, which Dante devotes to the treacherous. As mentioned previously, the devil is often known for being prideful, and pride has even been called the “first sin”, leading to Lucifer challenging God. However, Dante considers the betrayal of God by Lucifer to be the worst sin, regardless of whether pride was what motivated his treachery. Taking away the devil’s pride also works to strip him of his power and control. Pride is a feeling that carries with it confidence and self-satisfaction, and it allows for a level of dignity. Dante deprives us of the devil who smirks, who laughs, who revels in his own evil, and instead gives us a crying victim in the face of God’s punishment.

Even though in modern day, the confident trickster devil figure is what most would likely think of if told to imagine the devil, it does not take away from the significance of Inferno or Dante’s take on what Lucifer looks and behaves like. He deprives satan of his uniqueness and power, making him just another sinner to be punished. Although certainly it was not Dante’s intention to suggest pity or sympathy for the devil, portraying Lucifer as a weeping victim of his own actions opened pathways for more complex, unique, and nuanced takes on the devil.

Featured Image: Lucifer King of Hell by Gustave Doré, 1861-1868. This work is in the public domain.

Images: The Fallen Angel by Alexandre Cabanel, 1847. This work is in the public domain.

Earthly Vanity and Divine Salvation by Hans Memling, 1485. This work is in the public domain.

Satan in the Frozen Lake by Jean-Edouard Dargent, 1870. This work is in the public domain.

Dante and Virgil in Cocytus by Gustave Doré, 1866. This work is in the public domain.