by Elijah McNemar

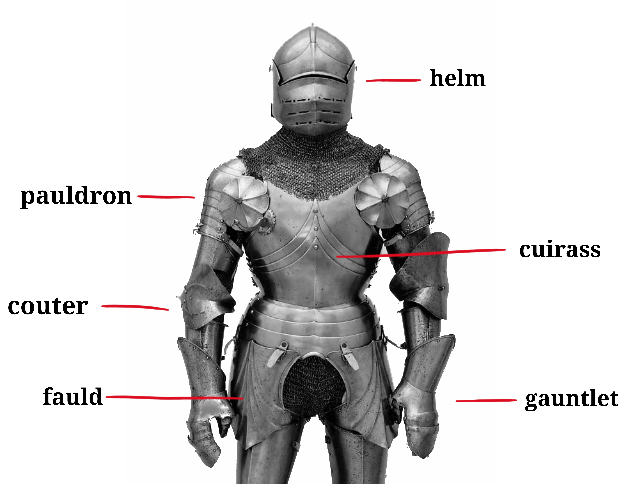

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City holds an astonishingly large collection of arms and armor within their archives. One specific set, seen in Image 1, although not incredibly flashy, is rather fascinating. It did not belong to anyone famous, nor does it have some sort of priceless metal or stone within it. It is the composition that is remarkable, from a historical standpoint. As with most armor in the 15th century, this piece shows a transitional period from the 14th to 16th centuries. An example not only of where armor once stood, given its inclusion of chainmail around the neck, it points forward to where it was heading, as can be seen in the helm, culminating to make a fascinating piece.

The Helm

To begin, the helm is an example of a transitional piece somewhere between a sallet and a close helm (Images 2-4). Sallets were wildly popular in a large portion of medieval Europe, but they found their niche in Germany and Italy. This helm in particular is closest to a sallet due to the size of the protrusion near the base of the skull, but it shows the shift towards the close helm, which would become the standard in the late fifteenth to the mid-sixteenth century. The visor in particular is reminiscent of a later design referred to as a bellows visor, which was popular on close helms. Sallets and early close helms, offering not much if any protection below the chin, were also worn with bevors, which protected the throat and chest.

The Pauldrons & Maker Stamp

Something notable about this set is its origin‒ many of the pieces were brought from different sources in order to create a composed set of armor. This is, in a sense, historically accurate, as it was common for high-ranking soldiers to buy pieces of armor as they could from different makers. The eclectic nature of this set displays multiple different aesthetic styles, all of which are regionally influenced. The armor is embossed throughout with maker’s marks, though the sources are unremarkable or unreadable. Though it is not necessarily deducible who exactly made them, the designs do follow those seen throughout both German and Italian armor. For example, while the helm is of Italian design and make, the right pauldron, or shoulder guard, was stamped as being created by Matthes Deutsch, a famous German armorer (Images 5 & 6).

The Cuirass

Moving from the shoulders to the chest and back, the cuirass of this set mirrors the pointed segment design of the pauldrons, likely sharing a similar origin despite the lack of a maker’s mark on the piece itself (Image 7). A cuirass is a combination of a chest and back plate. The right-hand side of the chestplate has a protrusion that was used to rest a lance. Contrary to popular belief, it was not designed to hold the weight of the lance for the wearer, but instead it was used to stop the lance from moving backwards on impact.

The Couters, Gauntlets, & Faulds

The arms are largely simplistic in their design, with the exception of the elbow cops, also referred to as couters. These couters have an asymmetrical design, with the left side the larger of the two (Image 8). Most cavalry armor is designed this way as it was cumbersome and redundant to arm a fighter on horseback with a shield. The gauntlets are a textbook example of mitten or clamshell designs (Image 9). The faulds, which are the leg protection attached to the cuirass, are of the same general design as the cuirass itself (Image 10). Lastly, the rest of the leg is basic and has a symmetrical design, unlike the couters.

Conclusions

Though this piece is wonderful, as previously stated, it is not currently on display at The Met. However, for those interested in arms and armor, the collection currently on display is quite remarkable, and it was a privilege to see over this past summer in person. Should The Met be too far away, and outside the realm of reasonable expense, I also recommend the Cleveland Museum of Art, not only for their impressive collection of arms and armor, but also for their collection of other artwork. Although certainly not as vast as The Met, the Cleveland Museum of Art is, in its own way, just as lovely. One can very reasonably see the museum in full in only one day, which proved difficult to do at The Met. Their Armor Court is on display and can also be viewed in a virtual tour on their website. Although far removed from their time and use, the armor in these exhibits prove undeniably useful in the study of medieval art, armor, and history.

Elijah McNemar is a freshman at Ohio Wesleyan University and plans to major in history. He is fascinated by arms and armor from around the world, specifically enjoying European pieces from the 14th to 16th centuries. He loves art and music and wants to work as a museum curator or archivist as a career. He has many hobbies and is a novice blacksmith, poet, musician and writer.

Cover photo by Henry Hustava on Unsplash.

Images courtesy of the The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/24814, under an Open Access (OA) and public domain policy.