Written by Roland McGurr.

If asked to consider the vampire, most people would imagine the portrait of the vampire that was popularized and immortalized in Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel Dracula: a humanoid figure with an aristocratic air and something registering to an onlooker as not-quite-right, whether in disposition or features. The traits that may begin to materialize in this mental rendering would be fangs, pointed ears, and a ghastly pallor. This is the prototypical vampire in our culture today, though differing versions of the vampire have been present for millennia.

This characterization of the vampire in our pop culture is an interesting amalgamation of folkloric elements and history from across cultures and centuries, culminating in a vision now nearly universal. There is a long tradition in these legends and literatures forewarning against the vampire as a malevolent imitation of humanity, setting the vampire at the intersection of themes of sexuality, religion, politics, and death. The longevity of the vampire comes from its ability to allow people to examine their own values through a twisted reflection, and while associations and aspects of the lore have been altered over time, the vampire has functioned this way since its inception.

Blood and death are inescapable parts of human existence, and it is only natural that they should crop up frequently in the stories people tell, especially when considering what the world looked like before modern medicine and science. This association of blood and life is an early one, and the vampire and its bloodlust also has ancient origins.1 Romans spoke of blood-sucking ghosts, an idea of the vampire more paranormal than some others. What makes these ghouls really resemble the modern vampire is the fact that they were a means of cultural projection. These ancestors of the vampire were associated with the Goths and their misdeeds, who Rome was at war with.2 This trend is not unique to this instance: the vampire cannot be extricated from its role as a dividing line between us and them, between the dignified and the depredators, the virtuous and the wicked.

Other ancient depictions of vampires establish fear due to their upheaval of order and their disruption of moral standards, another way of setting individuals against one another. There was great interest in vampires as a creature that returns from the dead to feed on the blood of children, tying together themes of blood and purity, an essential fixture of many vampire tales. Stories such as these have origins in Ghana, Babylonia, the Philippines, and Greco-Roman mythology;3 clearly, there is an extensive human interest in the idea of such a creature and what it seeks to interrupt, and it continues to this day, even as the historical context shifts.

Dracula is praised, rightfully so, for how it manages to depict the anxieties of the Victorian age through its villain and the discussion surrounding him. Count Dracula serves narrative purposes, but overall, he is “othered” from the heroes of the story by his foreignness, which his vampirism is tied to. The unfamiliar Dracula and his eastern associates are seen to be polluting Britain with their immorality and promiscuousness. The vampire, in all its iterations, is either the result of or the cause of societal ills; it’s a mechanism of confrontation.

Ironically, given the xenophobia present in the novel that has typified the vampire, many of the characteristics and ideas recognizable in the modern vampire come out of Eastern Europe. It is difficult to track an exact origin, but many early Slavic stories connect the vampire with sinners or heretics who come back from the dead, or those with desecrated or disturbed graves who rise.4 There is a clear correlation here between the vampire and the societal expectations of conduct in these societies. A tale like this gives someone a reason to fear an excommunicate, for example, for more than just a distaste towards their perceived lack of faith: when this heathen dies and becomes a vampire, they could endanger everyone. Concerns spawning from these stories may encourage the continuation and enforcement of the pre-existing values, such as those regarding care for the dead, so that loved ones do not return as vampires.

Other details that evolved in Slavic tradition are identifiable as classic vampire tropes in the modern day. The idea that vampires can be preserved as they were in life in their grave, not decaying like a zombie, was a belief.5 The bat imagery that is often coupled with the vampire did not arise until reports of “blood-sucking” bats arrived in Europe from explorers in the Americas, and it was quickly integrated into the existing beliefs.6 The idea of driving a stake through the heart of the vampire to vanquish it is thought to be inspired by some brutal execution practices in different parts of the world,7 a further example of that which is different or horrifying in the real being adapted to the vampire.

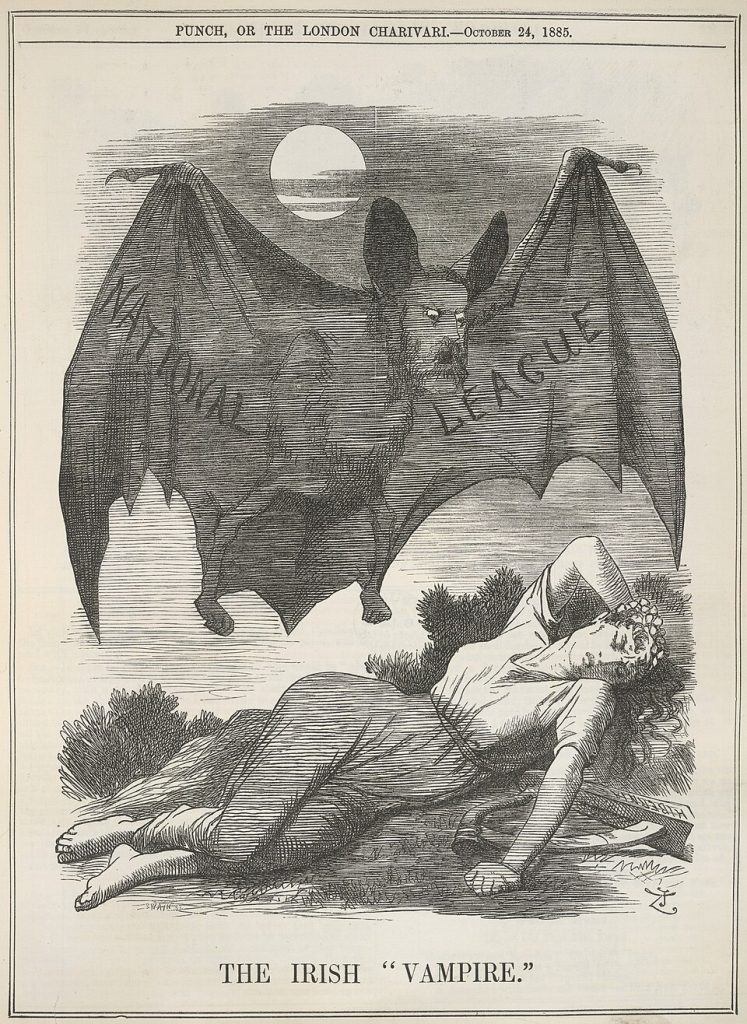

In the late 17th and 18th century there was a Renaissance in—among other things—the dialogue regarding the vampire. Not unlike our modern day “Satanic Panic”, many people at this time became worried about the threat of vampires. Due to this, earnest discussions about and reports of vampires made their way into the news, and people wrote scholarship and treatises on how to confront the issue with a diverse array of specific concerns. There was a scientific perspective with two extremes: those who thought the preoccupation with vampires to be a manifestation of mass-hysteria, and those who used it as a way to scrutinize observed maladies and death.8 It was used in theological discussions as well as in political metaphors, notably by Marx.9 This period seems to represent a transition in the vampire legend from a supernatural creature haunting villages into a framework to dissect contemporary ideas regarding science, religion, and philosophy, and how these topics overlapped. Out of this development comes the era of Dracula.

Bram Stoker did diligent research for Dracula, and one type of source he consulted whilst crafting and populating his eastern setting was the travel narrative, including one written by his brother.10 Though the ones he interacted with were not written by inhabitants of the regions themselves and instead those passing through, they provided him with ideas (however potentially misinformed or biased) about peoples and superstitions of Eastern Europe, which, as established here, was a hotbed for vampire legends. One of his sources, an 1885 essay by Emily Gerard, goes into detail about some of these vampire tales,11 many of which resemble the Slavic tales, making the evolution to Dracula clear. Another source of inspiration was Vlad the Impaler, or Vlad Dracula, a 15th-century despot who impaled his victims, evoking again the staking of the vampire.11 Such viciousness can be hard to comprehend, and it makes sense to consider that stories told about someone who inspired such terror may adopt folkloric elements to explain away such evil, or to separate it from humanity. Stoker’s work is very geopolitically concerned, but it is far from the first vampire story to seek connection between vampires and the state.

While this is in no way an exhaustive overview of all the existing vampire myths and their precise genealogy, these examples demonstrate the beautiful nuances that have always permeated the vampire legend in their musings on humanity and death and eventually politics, including the imperialist concerns at the center of the world’s most popular vampire media. Though the role of the vampire evolves as societies shift their ideologies, the human propensity for the macabre never wanes. Both a proto-Slavic peasant faulting the undead for the plague on their crops and a 21st-century partygoer dressed as a count and wearing plastic fangs on Halloween are participating in a rich tradition of the story of the vampire.

1 Beresford, Matthew, “Thee Ancient World: Origins of the Vampire” in From Demons to Dracula : The Creation of the Modern Vampire Myth. (London: Reaktion Book, 2008), 21.

2 Groom, Nick. “Dracula’s Pre-History: The Advent of the Vampire,” in The Cambridge Companion to Dracula, edited by Roger Luckhurst, (11). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

3 Beresford, “Thee Ancient World”, 20-23.

4 Oinas, Felix, “Eastern European Vampires & Dracula,” Journal of Popular Culture 16, no. 1 (1982): 108, DOI: 10.1111/j.0022-3840.1982.00108.

5 Oinas, “Eastern European Vampires & Dracula,” 109.

6 Oinas, “Eastern European Vampires & Dracula,” 109.

7 Oinas, “Eastern European Vampires & Dracula,” 110.

8 Groom, “Dracula’s Pre-History,” 16-17.

9 Groom, “Dracula’s Pre-History,” 22.

10 Lucendo, Santiago. “Return Ticket to Transylvania relations between Historical Reality and Vampire Fiction,” in Dracula, Vampires, and Other Undead Forms, edited by Edgar Browning and Caroline Joan (Kay) Picart, (118) New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, (2009).

11 Gibson, Matthew. “Dracula’s and the East,” in The Cambridge Companion to Dracula, edited by Roger Luckhurst, (100-101). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

12 Groom, “Dracula’s Pre-History,” 22.

Roland McGurr is a senior at Ohio Wesleyan University majoring in English, Classical Studies, and Medieval Studies

Featured Image: The Vampire by Philip Burne-Jones, 1897. This work is in the public domain.

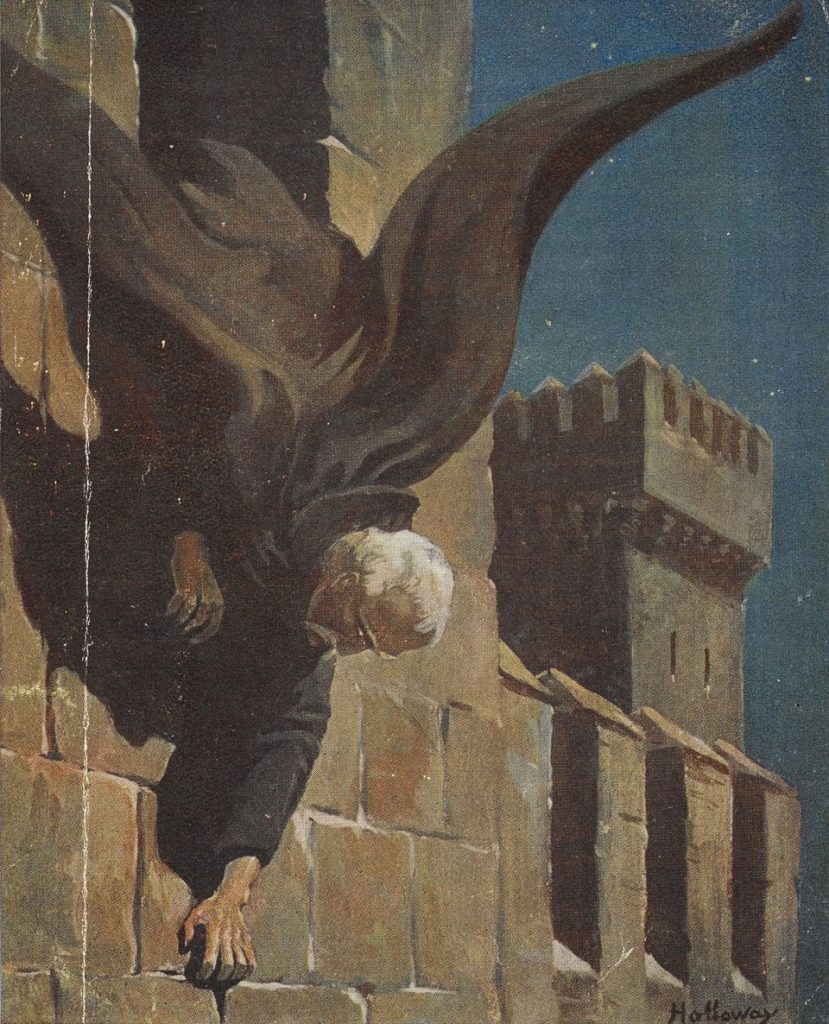

Images: Dracula by Edgar Alfred Holloway, 1919. This work is in the public domain.

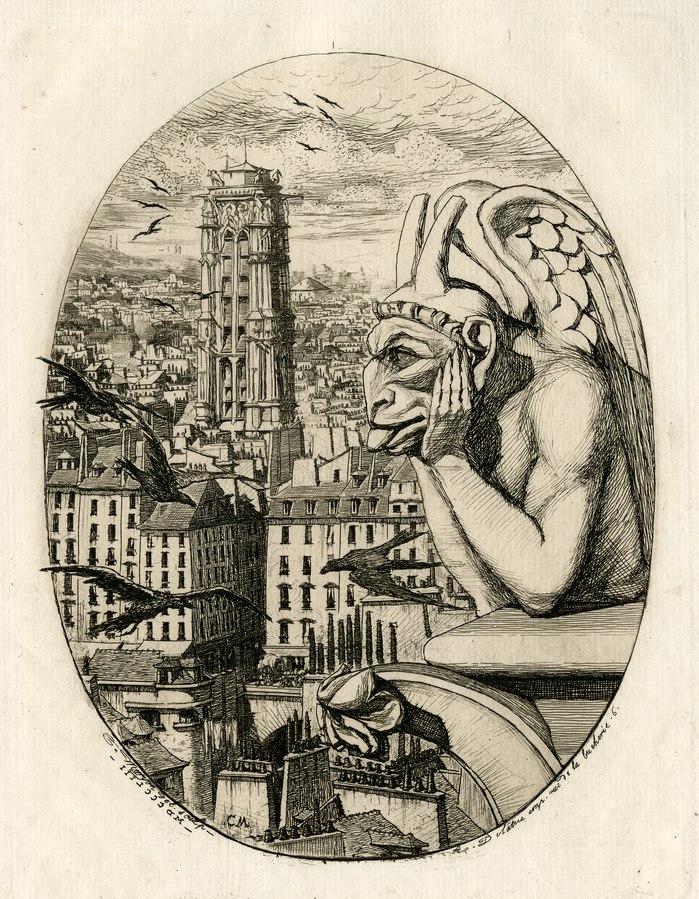

La Stryge by Charles Meryon,1853. This work is in the public domain.

The Irish “Vampire” by John Tenniel, 1885. This work is in the public domain.

Dracole Wayde by Markus Ayrer, 1499. This work is in the public domain.