The tales of King Arthur and his knights are some of the most well-known stories around the world, subject to many interpretations and adaptations, with one of the best adaptations being that of John Steinbeck, author and winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature. Having admired Sir Malory’s arthurian tales as a child, Steinbeck began to write his own version titled The Acts of King Arthur and His Noble Knights. Published posthumously, the work is incomplete; however, letters survive that give an indication of his interests while writing the works, and what he wanted from them. Originally, Steinbeck had set out to modernize the language, writing in his introduction to the tales, “I wanted to set them down in plain present-day speech for my own young sons, and for other sons not so young—to set the stories down in meaning as they were written, leaving out nothing and adding nothing—…” (3). However, despite intending to only modernize the language, when it came to women, Steinbeck altered the stories quite heavily. Steinbeck seemed unsatisfied with Malory’s treatment of women, as in his letters he writes, “I am going to have an essay about Malory’s feelings on women” (381) and “I am constantly amazed at the feeling about women. Malory doesn’t like them much unless they are sticks.” (385). One of the strongest examples of his alterations is the character Lyne, in the tale of “Gawain, Ewain, and Marhalt”.

The tale of “Gawain, Ewain, and Marhalt” in Malory’s 1954 edition is rather short, but follows the quest of the three knights, as they each choose a damsel of a different age, and go on adventures with their respective damsels, with the intention to meet back in a year. In Malory’s edition, none of the three damsels are named, whereas in Steinbeck, he gives the eldest maiden, whom Ewain chooses, the name of Lyne. Some have criticized Steinbeck for only naming one of the damsels; however, this is an intentional choice Steinbeck made, in order to take a dig at Malory. In the case of Marhalt and his damsel companion, Steinbeck calls attention to the fact that her name isn’t mentioned in the entire year they spent together, writing, “What is her name, sir?”, to which Marhalt responds, “I never thought to ask”. (Steinbeck, 187), a scene that did not exist in Malory’s text. Steinbeck is expressing his distaste for Malory’s treatment of women and the lack of value the knights place on them. Lyne being named and the other two being nameless serve the same purpose, of highlighting Arthurian women. In the unnamed women, it is to highlight the unfair treatment they receive, as they are viewed as tools, or perhaps “sticks”, whereas Lyne, as we will come to see, is meant to be a far more positive portrayal of women, as containing depth and complexity.

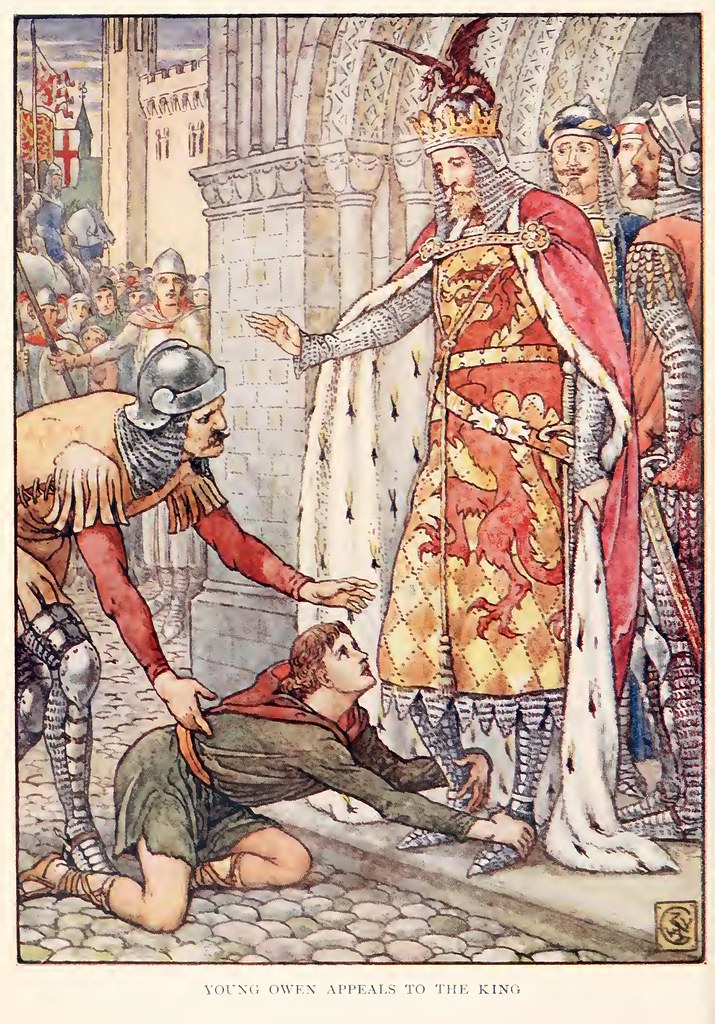

An example of a medieval women cross-dressing, as Lyne would have done.

Lyne works as a compelling character because of the duality that exists within her, that is, in her expression of both femininity and masculinity. Lyne, as she exists in Steinbeck’s tale, is a trainer of knights, nearly a warrior herself. She offers her background to Ewain, saying, “A little girl, hating embroidery, I watched the young boys practicing and I hated the hobbles of a gown. I was a better rider than they, a better hunter, as I proved, and alone with quintain I proved myself with spear. Only the accident of girlness prevented me from being more than equal to the boys. Hating my limiting sex, I sometimes dressed in boys’ clothes, masked myself against shame, and waited in a forest glade like a child errant for boys and young men. I beat them wrestling and with quarter stave, stood against them with sword and shield…” (Steinbeck, 189). Steinbeck suggests here that there is nothing in skill stopping women from being talented knights, but rather societal constraints of the time. Ewain’s response, “This is a tale of terror and unnatural” (189), while reflective of how people of the time might feel, is made memorable by Lyne’s reply, “Perhaps it is…I wonder how unnatural?” (189). Lyne subtly suggests that she can’t be the only woman who is just as competent in martial skill as men, or who longs for that kind of freedom. Steinbeck proves this later on, at least from the framework of desiring the freedom men have, when in the story “The Noble Tale of Sir Lancelot of the Lake”, he has Guinivere say, “Sometimes, I wish above everything to be a man, sir. But I must wait. My only adventures are in the pictures in colored thread of the great gallant world.” This, too, is a scene that Steinbeck created, not modernized, as Steinbeck seems to desire some evolution of thought toward Arthurian women. We can see this in Ewain, who at first is uncomfortable with Lyne’s story, and then grows to respect her deeply.

In terms of femininity, Lyne displays this too, as she expresses softness that is connected to maternal feelings and care. Though Lyne has high standards in her training, she does not deny Ewain praise when he performs well, and the gentle, maternal touches she occasionally offers him, Ewain considers accolades. The depth of the bond they have forged is revealed in a bittersweet moment, as they say goodbye when the year has ended. Ewain asks, “Will you go back to find another knight?”, and it is noted that he asks this “with jealousy” (219). The jealousy that Ewain expresses is important because it reveals that, despite Lyne being firm and exacting, Ewain values her and wants to be special to her. Lyne’s response, “Yes, I suppose I will. But I will be critical. It will not be easy. Oh, God! how dreadful it must be to have a son!” (219), is just as revealing of her emotional tethers to him (and perhaps to other knights that she has trained). Ewain, when he undertakes his journey, is still a young boy, and Lyne is likely experiencing the parental feeling of knowing that she’s done all she can to prepare him for the world, but that ultimately it is up to him to make good choices, and the fear, along with pride, that comes with letting a child grow up. Steinbeck pushes this even further, writing their goodbye as follows, “‘Then farewell, my lady,’ Sir Ewain said. And as he rode away he thought he heard her say, ‘Farewell my son’.” (219). This tender and heartbreaking scene, entirely invented by Steinbeck, reveals that his interest in women is well-crafted and thoughtful.

Steinbeck rejects the idea that Mallory’s tale supposes, that is, that masculinity is superior to femininity. Lyne being a fighter is not meant to suggest that women should only be held in high regard when they have masculine traits or what some would consider masculine skills. Both Lyne’s skill as a knight and her motherly tendencies towards Ewain were created by Steinbeck, and both are presented favorably. If he wanted to suggest masculinity as superior, he wouldn’t have added scenes that emphasize her femininity and softness, or display one of the roles that women can have, specifically that of motherhood. There is often this idea perpetuated that femininity and softness equate to weakness. Steinbeck creating a woman who so clearly displays strength associated with men, while also still having femininity within her, argues against this idea. Gender is not defining of character, and to write off all women as “sticks”, beings with no agency or complexity, is a disservice to the roles that women can and should play. Lyne is just one example of a woman whom Steinbeck writes such depth into. He gives Guinevere, the other two damsels, Nyvene, and even Morgan scenes that did not exist, which add to and deepen their characters. This alone makes Steinbeck’s The Acts of King Arthur and His Noble Knights an interesting and worthwhile read, though he also engages in adding scenes to deepen his understanding of some of the male characters, like Arthur and Lancelot.

Featured Image: The Arming and Departure of the Knights by William Morris, Sir Edward Burne-Jones, and John Henry Deale, 1890. This work is in the public domain.

Images: Jeanne d’Arc by Albert Lynch, 1901. This work is in the public domain.

Young Owen Appeals to the King by Walter Crane, 1911. This work is in the public domain.